Early Town Development

Tewkesbury was one of a number of demesne manors included in the honour of Gloucester. In an early and influential study of the Domesday Survey[1] it was cited as one of the largest manors in medieval England. Its exceptional size, reaching from the river Severn to the Cotswold scarp in the east, embraced a wide range of resources and economic activity, including the cultivation of vines. Before the Conquest the manor was held by Brictric, described as a 'great thegn', and it is his manors which appear to form the nucleus of the honour of Gloucester. Privileges granted by Brictric and later lords of Tewkesbury increased the resources of the manor and aided early urban growth there.

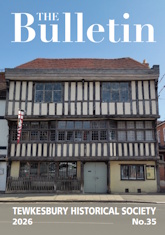

Tewkesbury is widely known for the survival of its old buildings. Some may be of medieval origin, but most date from between the 16th and the 18th century. These buildings front the three main thoroughfares in the town and it has been assumed that they occupy the sites of earlier houses built on characteristically extended and rectangular plots, defined by tenement boundaries and almost certainly of medieval date. Despite the large number of surviving old buildings, the comprehensive analysis of the documentary evidence by the Victoria History, and some below-ground investigation in the Oldbury, the evidence for charting the evolution of the town allows for many interpretations (see diagram).

What is certain is that the most potent factor in the town's development was the influence of secular lordship. Queen Maud established a market at Tewkesbury in the aftermath Of the Conquest and under Robert FitzHamon a Benedictine monastery was built; its church was consecrated in 1121. FitzHamon's motives included the creation of a mausoleum for himself and his descendants but his longer-term objective was to establish Tewkesbury at the confluence of the rivers Avon and Severn as an urban centre and as a base for the conquest of south Wales, the counterpart to the Norman fortification of the Old legionary fortress of Roman Deva by the earls of Chester. Tewkesbury served as such a base until Edward I's comprehensive campaigns of the late 13th century and the endeavours of the Despensers in the 14th century to emulate the Clares' conquests in Wales.

The creation of burgesses and the construction of the Norman abbey could have been the first stage in the forming of a planned medieval town. Evidence from the 1972/3 excavations in the town showed that in the Roman period and later the focus of settlement was on the highest ground, the Oldbury, The tradition of an early Anglo-Saxon monastery at Tewkesbury is not supported by archaeological or architectural evidence and it can only be assumed that if such a monastery or minster existed, it stood at or near the site of the remains of the Norman abbey. Blair and Sharpe (1992) have demonstrated the durability and persistence of the circular enclosure as the basic form of the pre-Conquest Anglo-Celtic monastery. If St Mary's Lane represents the northern segment of the boundary of such an enclosure, that possibility lends credence to the story of a hermitage or church being founded in the early 8th century on the bank of the river Severn. Wherever any early religious house may have been located, FitzHamon's initiative moved the centre of gravity of the settlement to the south-west. The choice of site for his monastery may have been influenced by religious considerations but it is more likely to have been determined by the supply of water provided by the stream to the south. The creation of the monastic precinct was just one stage in the town's development, and canalising the river Avon to drive the abbey's watermill also had the effect of defining the western boundary of the medieval town.

The reconstruction of the form and fabric of medieval settlements has been enhanced in recent years by the analysis of maps, complemented by the study of other historical and archaeological evidence. The approach commences with the definition of plan-units or areas which 'reflect, hypothetically, a phase or stage in the morphogenesis of a town's plan'[2]. Dr. Lilley's preliminary analysis, reported here, has defined four such Stages in the town's plan. Plan analysis indicates that the primary route through Tewkesbury followed the line from south-west to north-east along Church Street and Barton Street, a judgement based on the slightly sinuous line of this route in comparison to the more 'geometric' form of High Street, East Street, and Oldbury Road. This conclusion therefore supported the assumption that in prehistoric times a land route followed the east bank of the Avon river northwards[3]. It is likely that this route crossed the fluvial sand/gravel deposit which underlay the Oldbury area of the town. This situation was altered by the Roman military surveyors in the 1st century A.D. who affected a link between Gloucester and Worcester by a crossing of the river Avon at Tewkesbury; the detection, and confirmation of the line of the Roman road approaching the Mythe from the south[4] would indicate that the Gloucester-Worcester road crosses the river Avon at or near the crossing chosen by the Romans. The construction or refurbishment of the Avon bridge by King John in the early 1200s testifies to the importance of the road to Worcester at that time.

From the north, the entry of the road into Tewkesbury, having crossed the Avon bridge, is now marked by a sharp turn to the south-west, along High Street, but evidence from boundary ditch alignments in the excavations at the Oldbury suggested that in the Roman period the road continued south-eastwards to the higher ground of the Oldbury where it forked, one branch heading east towards the Cotswolds, the other turning south for Gloucester along the line of the prehistoric route. Although the primacy of the SW-NE line of communication outlined above is highly plausible, there is an alternative view that would argue a north-south line as the earlier route through the river-side settlement. That line would have followed the later Oldbury Road, on the highest land in the area, passed over or through the river Swilgate (near the present footbridge), and continued southwards to resume the line of the present main N-S road at or near Margaret's Camp. A road constructed in the 1st century would not have needed to follow the northern bank of the river Swilgate to a crossing below the scarp of Holm hill. In 19th century antiquarian discussions of Tewkesbury's topography[5], the existence formerly of a more direct route southwards from the town was alluded to but never identified. Evidence for such a route is indicated by Croome's 1825 map of Tewkesbury[6] in which an alignment of field boundaries south of the town can be interpreted as the line of a former N-S road. There is supporting evidence from Ernest Greenfield's discovery in 1967[7] during the construction of the King George VI playing field of Roman burials in stone coffins; such burials would have been outside the settled area and, in accordance with Roman burial practice, alongside the main route south from the town.

Evidence for the nature of the settlement in the Anglo-Saxon period is almost non-existent, with the possible exception of the post-Roman earthwork features recorded in the Oldbury. There a large ditch had been cut through occupation layers of the Roman period. Later there was a build-up of more than a metre of dark, silty soil, with few finds and cut into by medieval pits. The evidence for Tewkesbury manor provided by the Domesday Survey was, by contrast, of unusual quality and precision. In 1066 a hall and church existed there, together with people of varying social rank. Included in the population were 16 bordars. The role and status of bordars in late Anglo-Saxon England has recently been assessed (Dyer 1994) with the conclusion that they were in part involved in crafts and services, fulfilling tasks essential for the industry and trade which was changing the character of English settlements. The Tewkesbury bordars may therefore have been involved in manufacture and trade and Maud's establishment of a market and 13 burgesses there before 1086 can perhaps be seen as building on and formalising an existing situation, the burgesses being entitled to engage in trade. By contrast the 50 slaves recorded in 1066 were unlikely to have lived near either the hall or the church; they may have occupied land further north on the main road at the Oldbury. The picture that emerges is similar to that suggested by other Anglo-Saxon settlement studies, for example the Raunds project (Parry, forthcoming) in which the elements of individual settlements were physically separated from each other. Another view, however, argues that the Oldbury area was so called because it had been abandoned as a settlement and was characterised by the fossilised remains of earthwork enclosures. If the notion of polyfocal settlement is accepted then it is plausible that in 1066 the hall of the manor stood on Holm hill, a church was sited near the river, and a community of serfs lived at the earlier Romano-British focal point and provided the labour necessary to serve the great demesne manor.

The location of the Domesday church remains unknown and there is no firm evidence that it stood on the site now occupied by the Norman abbey. In the 1970s John Hopkins, master mason, responsible for the fabric of the abbey church, found a short length of wall, surviving to a height of c. 30 cms, in situ beneath the floor of the south transept and comprised of 'herring- bone' construction; the attribution of such construction exclusively to the period has however been questioned[8].

The construction of the abbey, following the unspecified 'waste and destruction' reflected in the marked fall in value of the manor recorded in the Domesday Survey, could have led to the road, if N-S in orientation, being diverted across the promontory of land on which the abbey was built. Although it was important for the monks to preserve the sanctity of their precinct, among their first considerations would have been the provision of an open space next to the precinct to accommodate religious processions and festivals and to allow an unimpeded and awe- inspiring view of the recently completed east end of the great church. A secondary but no less important concern was to exploit the potential for commerce offered by the main thoroughfare passing the precinct gates. St Mary's Lane is a semi-circular road half-enclosing an area of several hundred metres square on the west side of Church Street. That area may have provided a market for the pre-Conquest settlement or it may have been created as the market place of the early Anglo-Norman town. As with market places laid out in other early towns it could have been infilled as semi-permanent market stalls were replaced by shops with residential accommodation attached. The earliest secular structure recorded in the town, a vaulted basement of 14th- century date, is beneath a house (90 Church Street) standing on the corner of this area. It is possible that the town developed from the nucleus created by the monastery and the St. Mary's Lane 'market' and that the expansion took the only direction possible, to the north-east along Church Street.

A marked feature of early towns in Gloucestershire and elsewhere is the dominance of the market place, despite piecemeal infilling in the town's layout; 'the great majority of English town plans may be seen to be market-based'[9]. Tewkesbury would have been no exception and one place for a market would have been at or near the junction of the main roads from the south-west, north and east. The bounds of this market area cannot be defined with certainty but the tenement boundaries suggest that the properties in the angle of High Street and Barton Street are the result of haphazard infilling of a previously open space. By contrast the tenement boundaries further north on both sides of High Street are more regular and ordered. A trapezoidal area, bounded by Barton Street on the south, East Street on the north, High Street to the west, and Chance Street to the east and crossed by the original N-S route (Oldbury Road), could also once have been an extensive market area, subsequently 'colonised' by buildings evolved from market stalls. Unlike many other early English towns, the circumstances regarding growth and expansion operating at Tewkesbury were exceptional. The constraints imposed by the flooding of the rivers meant that there was continual pressure on the higher (and drier) land for building. One tenement boundary on the east side of the High Street describes a 'fault' line, particularly where it extends to the east to meet Oldbury Road, and may represent the northern boundary of a market area; at one end stood the Tolzey and the market cross, at the other the barn and stables of the earls of Gloucester[10]. From the cross, roads ran to the north for Worcester and Pershore, to the south-east for Gloucester and the Severn crossing, and to the east for the Cotswolds. The establishment of a market place on such a scale could coincide with the widely attested promotion of urban growth in the early 13th century[11]. Although there is no documentary evidence in its support, there is the possibility that it could have occurred with accession to the manor of the Clares who would have sought to exploit commercial opportunities.

A contrary hypothesis, based on the technique of map analysis, is that Tewkesbury, unlike the Cotswold wool towns, did not require extensive open market areas as its streets would have sufficed to accommodate market trade. This idea is supported by scrutiny of Lilley's plan-units which do not reveal evidence of plot formation from irregular infilling of open spaces. Lilley's provisional analysis also demonstrated that the present configuration of tenements in the angle of Barton Street and High Street was produced by a modification of the earlier frontage on Barton Street as a result of the creation of another frontage on a later N-S thoroughfare (High Street). In the provisional definition of a plan-unit including the High Street frontage it was noted that the largest tenements were on the west side of High Street; Lilley has suggested that this reflected the prosperity derived from direct access to, and control over, goods handled on the banks of the Mill Avon.

The stages in-the development of the town in the area between the abbey and the market cross and in the area of High Street remain speculative. Although possibly coincidental, the distance from Oldbury Road to the bank of the Mill Avon is in the region of c. 200 metres (220 yards). The property boundaries between Oldbury Road and High Street and in turn the Mill Avon, display at various points the reversed-'S' curve, which can be interpreted as the encroachment of settlement onto open-field land and the adoption of curving 'lands' as property boundaries and as access lanes between tenements[12]. This could represent several stages of development: the creation of the Mill Avon following an appropriate contour at the edge of the flood plain and relatively parallel to Oldbury Road; the resumption or layout of open fields on the Oldbury; and the creation of tenements along a new road (High Street) which crossed open-field land on its long axis but made a sharp turn at the north end near the crossing Of the river. The new road along which the town expanded was known as Oldbury Street in 1257 and High Street from the 16th century. The original Oldbury Road was reduced to a rear lane separating the town from an adjoining field which remained 'open' until 1811. Despite uncertainty over the location, the early establishment of the market led to the rapid expansion of the town. Although the town did not achieve corporate status until 1575 Tewkesbury had for long functioned with many of the characteristics and privileges of a borough. In reconstructing and interpreting the urban landscape, two broadly contrasting theories have been advanced. One sees the primary route as running E-W, with the other streets a later geometric imposition and the medieval markets functioning adequately within these early streets. The other suggests a primary N-S alignment (Oldbury Road) as the early corridor, with the designation of large rectangular and/or semi-circular areas for market spaces. These theories highlight the scope and need for future research, based on gathering dimensions of tenements by plan-unit and integrating other historical material into an urban database, to produce sound models for the relative chronology and form of the medieval urban landscape.

References

- Maitland 1892

- Lilley 1995

- Webster and Hobley 1968

- Sanders and Webster 1960

- Spurrier 1886; North 1890

- Glos. R.O., TBR/A 18/1

- V.C.H. Glos. 8, 110

- Taylor 1978, 760

- Platt 1976

- V.C.H. Glos. 8, 119

- Platt 1978, 30

- David Aldred, pers. comm.

Comments