Medieval Development of Tewkesbury

Reproduced from the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Transactions, Volume CV, 1997, from the article 'Excavations at Holm Hill, Tewkesbury'

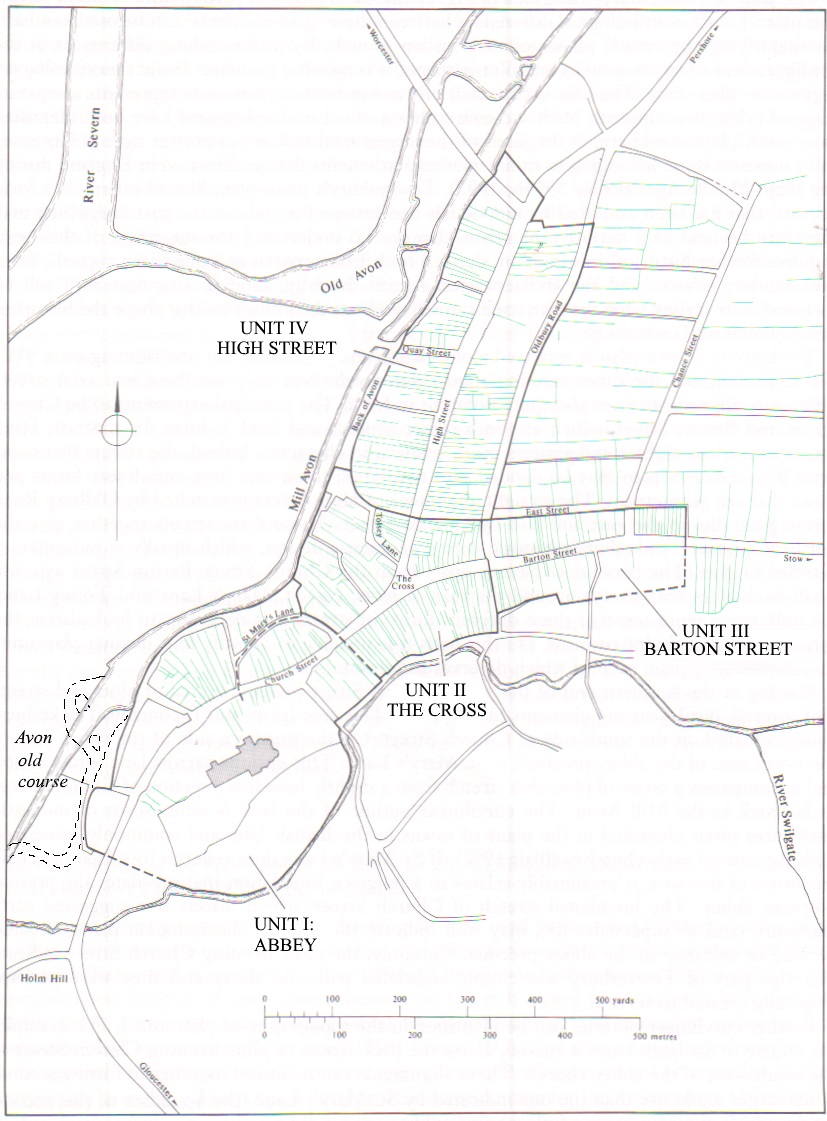

The plan of Tewkesbury, illustrated below, embodies different patterns and forms of streets and plots. Subtle morphological differences between these 'plan-elements' can be used as a basis for identifying conjectural phases of early urban growth. By distinguishing differences in the configurations of street systems and plot-patterns, it is possible to define distinct morphological regions or 'plan-units'. The idea is that each of these individual plan-units represents a separate stage of urban development. Such successive phases of urban development have been identified from town-plans elsewhere, in the plans of the largest medieval urban centres such as Coventry right down to those belonging to minor market settlements that proliferated in England during the High Middle Ages[1]. Tewkesbury's town-plan, like all others, is a form of 'text' that has been authored by individuals and groups throughout the past and which may therefore be read as a narrative of urban change. To understand the meanings of this 'text' requires further historical information, derived both from written and unwritten records, from documentary sources and the archaeological record. Initially, though, attention here will be focused on revealing what the plan itself can tell us about the influences that shape the historical development of Tewkesbury.

Tewkesbury's town-plan is arranged along two primary axial-streets, one running on a SW–NE alignment and the other running almost due north. Not only are these two axial streets differently aligned, they are also quite different in form. The principal axis seems to be Church Street and Barton Street, which are both rather sinuous and fluid in form. In contrast, High Street is much straighter and appears more artificial in character, Indeed, the streets that comprise Tewkesbury's plan may be divided into two types; those that have curvilinear forms and those that are geometrical. The straight alignment of High Street is matched by Oldbury Road running parallel to the east and also by Chance Street. These three streets together give the northern part of Tewkesbury's historic core a geometric design, which usually is indicative of planned origins. The curvilinear streets, apart from the Church Street-Barton Street axis, are small back-lanes that stretch around the rear of plots, e.g. St. Mary's Lane and Tolsey Lane. To help make more sense of these different forms of streets it is necessary to look also at the forms of associated plot-patterns, On this basis it is possible to identify four distinct plan-units in Tewkesbury's plan, each of which deserves some comment.

Starting at the southern end of the town, Church Street pierces an area of plots and streets that, overall, display strong elements of curvature. This area (plan-unit I) contains Tewkesbury abbey, situated on the south side of Church Street. On the northern side of the street, just to the north-east of the abbey precinct, is St. Mary's Lane. This curious narrow lane forms a loop and encompasses a series of plots that stretch from a slightly broadened section of Church Street as far back as the Mill Avon. The curvilinear outline of the lane is reminiscent of monastic enclosures often identified in the plans of towns in the British Isles and commonly associated with the sites of early churches[2]. If St. Mary's Lane does reflect a fossilised monastic enclosure of this sort, it presumably relates to a religious foundation that pre-dates the present Norman abbey. The broadened stretch of Church Street, which bisects this suggested early enclosure (and so supersedes it?), may well indicate the site of a later market place, situated outside an entrance to the abbey precinct. Certainly, the plots fronting Church Street indicate that this part of Tewkesbury was closely associated with the abbey and they were perhaps originally created to serve it.

Further curvilinear outlines can be identified in the topography of plan-unit I. For example, the course of Swilgate Lane is curved, as are the back-fences of plots fronting Church Street to the south-west of the abbey church. These alignments can be linked together to form a second, much larger enclosure than the one indicated by St. Mary's Lane (the boundary of this second 'enclosure' is the plan-seam of plan-unit I). The present abbey precinct is, of course, a third enclosure. However, these 'enclosures', delimited by the curving nature of plots and streets around the abbey, do not together make up a coherent, uniform pattern, but instead, overlap one another. The multiplicity of these different curved features is perhaps a reflection that each of the 'enclosures' has a separate origin, with each representing a certain stage in Tewkesbury's ecclesiastical history. According to 12th-century sources, there are traditions of a monastic foundation at Tewkesbury dating to the early 8th century[3]. The long-standing continuity of Tewkesbury as a place of Christian worship would help to corroborate the view that the morphology of plan-unit I reflects changing patterns of pre-Conquest monastic settlement.

To the north of the area of plan-unit I, the Church Street axis curves towards the east and, at the junction of High Street, becomes known as Barton Street. This road junction, the Cross, is the focus of an area (plan-unit II) which is markedly different in form from other parts of Tewkesbury's town-plan. The Cross is a slightly broadened stretch of street fronted by three series of plots, each with rather regular forms. The broadening of this street and its name reflect its former function as a market place, but in character the street is quite unlike the large market places that were often located outside the gates of pre-Conquest abbeys in Midland towns, and it is also unlike the large cigar-shaped market places so characteristic of medieval new towns, such as Burford, Moreton-in-Marsh and Chipping Campden, established in the Cotswolds during the 12th/13th centuries for livestock markets[4]. Instead, the relatively unpretentious dimensions of the Cross are more akin to commercial streets developed during the 11th century, such as Earl Street in Coventry and High Street in Southampton[6].

The plots fronting the Cross on its western side stretch back to the Mill Avon and extend along the street from St. Mary's Lane to Tolsey Lane. The latter leaves High Street close to the Cross and then curves away northwards behind plots fronting High Street (Fig. 1). On the east side of High Street, the curving alignment of Tolsey Lane coincides with a primary plot-boundary which is itself aligned with East Street. Taken as a whole, this alignment represents a prominent morphological boundary, and it may reflect a pre-urban feature. Certainly, this boundary demarcates a clear difference between the geometrical forms of streets (and plots) to the north and the more fluid forms of streets and plots of plan-units I and II to the south. The plots fronting the north side of the Cross, in the angle between High Street and Barton Street, have had their tails sub-divided to form derivative plots which front High Street. However despite these sub-divisions, the surviving primary plot-boundaries within this corner-block show that the original principal frontage was not High Street but Barton Street. This series of primary plots extends eastwards along Barton Street as far as Chance Street. Like the plots on the west side of the Cross, those on the south are quite deep and curving. The overall homogeneity reflected in the form of these plot-patterns, together with the broadened street-space, suggests that the area of plan-unit II was established to accommodate and stimulate increased commercial activity in Tewkesbury. One possible context for this development is the 'new market' and borough, which, as Domesday Survey records, was founded by Queen Maud soon after the Norman Conquest.

To the east of the Cross, along Barton Street, the plots are shallower and more rectilinear than those in plan-unit II. The back lane, East Street, is indicative that this part of Tewkesbury was planned and formally laid-out, although the sinuous form of Barton Street spoils the overall geometry of plan-unit III. In contrast the orthogonal nature of High Street and its associated plots show much clearer indications of geometrical design. High Street itself, as noted above, is straight along its whole length and is artificial in appearance. At its northern end, the straight alignment stops and High Street takes on a more fluid form. This pattern is also followed by Oldbury Road which runs parallel with High Street and acted as a back lane for plots fronting the street's eastern side. The implications of this are that High Street and Oldbury Road were at some time subject to realignment and straightening, in association, perhaps, with the laying out of plots along its length. The plots fronting High Street are a little deeper on its west side and stretch up to a back lane (a continuation of Tolsey Lane) called Back of Avon, which follows the river side. The dual river- and street-frontage would once have made these particular High Street plots lucrative assets for their property holders. Indeed, the close arrangement between river and road is surely no coincidence, and High Street was perhaps designed with the idea that a river-side frontage would enhance the commercial position of Tewkesbury as a small port situated mid-way between Gloucester and Worcester at the confluence of the Severn and Avon rivers. In this sense, the straight cut of the Mill Avon and the realignment of High Street could have been contemporary developments.

Although High Street, Back of Avon and Oldbury Road share consistent geometries, the associated plot-patterns reveal subtle signs that they were laid out over former arable strips. The slight 'S'-shaped curve of some of the boundaries of plots along High Street, particularly at its northern end, is reminiscent of the curve seen in fields of ridge and furrow, To the east of Oldbury Road there are further indications of relic field patterns in the arrangement of field boundaries shown on the Ordnance Survey plan (cf. Fig. 1). The impression given by these pre-urban features is that the area to the north of the curving boundary delimited by Tolsey Lane had once been a large arable field which subsequently formed the basis of a phase of urban development. Urban property would have been a more profitable use of land than cultivation, especially along the river frontage when High Street was laid out. In this case, perhaps the relic field lands to the east of Oldbury Road were also earmarked for urban development but were not built over? If so, this would help account for the similarity between the geometrical form of East Street (which contrasts with the form of Barton Street, as stated above) and the straight alignments of High Street and Oldbury Road. Equally, the straight alignment of Chance Street, which runs parallel with High Street, could originally have been part of this same scheme but as it has no associated plot-series this street presumably remained undeveloped (at least until the 19th century when it became the focus of renewed building activity).

As a whole it looks as if the area north of plan-units II and III was deliberately reconfigured for urban development, but that only one part of this area, the lucrative riverside frontage and High Street, was properly built up. Also, the geometrical forms of the streets and plots appear to have been imposed on an earlier landscape of field-lands, which in part survived. The development of this area was evidently designed to encourage further urban activity at Tewkesbury. As such, this area (plan-unit IV) perhaps represents a stage of urban expansion belonging to the 12th century, since this was a period when geometrical and orthogonal town designs became more common in England, especially during the years following the civil wars of Stephen's reign[5]. Moreover this temporal context relates to a surge of interest in Tewkesbury, particularly under John, as is indicated in the possible rebuilding of the first-floor hall at Holm hill and the construction (or refurbishment) of a bridge over the Avon at the northern end of High Street (close to but possibly not on the site of the present King John's bridge). If these interpolations are accepted, then the likelihood exists that High Street (plan-unit was established under royal authority. Likewise, following Domesday, the area of the Cross (plan-unit II) was also probably a royal initiative. In effect, therefore, Tewkesbury's town-plan seems to have been shaped initially by ecclesiastical control and subsequently, by royal interests. Although speculative in nature, these observations provide a conjectural view of Tewkesbury's early topographical development; starting with small religious community and settlement in the pre-Conquest period (plan-unit I) which, after the Norman Conquest, was successively extended, first by Queen Maud in the late 11th century (plan-unit II), and then twice in the 12th century (plan-units Ill and IV), latterly perhaps by King John.

This preliminary analysis of Tewkesbury's town-plan offers a spatial framework in which to place the fragments of its archaeology. The temporal dimensions of this framework can clearly be argued with, but with relatively little written evidence relating to Tewkesbury's early history, the morphology of the town's streets and plots becomes a valuable means of supplying an additional source of historical information. Such an approach, so often under-utilised, relies on the synthesis of cartographic, documentary and archaeological material, which in turn depends on continued inter-disciplinary co-operation. Unfortunately, the continued erosion of Tewkesbury's historic urban fabric has left some large holes in its plan. As is so common in small towns, modern redevelopment has eradicated the lines of ancient plot-boundaries. Efforts to safeguard these formerly conservative and long-lived townscape features are needed, since their removal spoils for ever the intrinsic quality of town-plans as a source of information for geographers and archaeologists alike.

References

- Lilley 1994b; 1995

- Blair 1992

- Binns 1989, 87

- Lilley 1994a; Slater 1996; Beresford and St. Joseph 1958

- Lilley 1995; Lilley forthcoming

- Lilley forthcoming

Comments