The 1714 Coronation Riot in Tewkesbury

“That King George has no more right to the Crowne than my Arse” 1

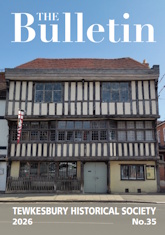

Some Tewkesbury based readers may have sat in the ‘Secret Garden’ of the Tudor House Hotel enjoying a drink and read the following inscription set above a door: “THIS OLD OAK DOOR CARRIES THE BATTLE-AXE SCARS INFLICTED UPON IT BY JACOBITE RIOTORS DURING THE CORONATION OF KING GEORGE I”. When I read this, I was a little surprised that Tewkesbury had serious Jacobite supporters as I always thought that the town was, in the past, significantly non-conformist Protestant, and simplistically thought of the Jacobites as all being Catholics. Looking into the incident and its background I have learnt more about the town in the period and come to appreciate that what is termed ‘Jacobitism’ in fact covers a wide range of ideas and motives.

The exile of the Catholic King James II, following the ‘Glorious Revolution’ of 1688 and the ascension to the throne of Protestants King William III and Queen Mary II, with the resulting years of dissension, is often portrayed as a simple religion based conflict – the actuality was far more complex with diverse groups on both sides of the argument. In the wake of the new order, it was thought that a successive Protestant monarchy was assured. However, the new joint monarchs, William and his wife Mary, failed to have children. Their successor, Mary’s sister Queen Anne, despite eighteen pregnancies had no living children by the year 1700.

This state of affairs prompted Parliament to pass the Act of Settlement in 1701. The legislation decreed that the crown was to pass to Anne’s cousin, Sophia, Electress of Hanover, granddaughter of King James I, and to “the heirs of her body being Protestants”. This despite there being over fifty Catholic people with closer claims to the throne by the rules of inheritance.2 The closest of these claimants was James Francis Edward Stuart (nicknamed the ‘Old Pretender’), half-brother of Anne and son of the exiled James II who had died in 1701.3

To complicate matters further, Sophia died on 8 June 1714 aged 83 – she had collapsed in the gardens at Herrenhausen, Hanover, after rushing to shelter from rain. Queen Anne followed her two months later after suffering a stroke.4 One of Anne’s doctors, John Arbuthnot, wrote to Jonathan Swift, “I believe sleep was never more welcome to a weary traveller than death was to her.” 5 Sophia’s death meant that the succession fell to her son, the non-English-speaking, fifty-four-year-old, George Louis (in German: Georg Ludwig).

It is of local interest that Anne had made George’s eldest son, George Augustus (later King George II) Baron of Tewkesbury in 1706. His association with the town was also evident in him attending horseracing at Tewkesbury during the 1720s when Prince of Wales.6

The country was split over George I ascending to the throne. This division dated back to the ‘Exclusion Crisis’ of 1679-1681 when attempts were made to exclude the Catholic Duke of York from becoming king after his brother Charles II. Broadly speaking, the Tories were opposed to the exclusion and the Whigs supported it. Tewkesbury at the time of the crisis had two Whig MPs, Sir Henry Capell 7 and Sir Francis Russell.8 Capell was the son of Arthur Capell, 1stBaron Capell of Hadham, who fought for the Royalists in the Civil War and was beheaded on the orders of Parliament in 1649. Although Henry Capell initially opposed exclusion, he and Russell both became firm campaigners for it; to no avail of course, the Duke of York became King James II in 1685.

The advent of the Glorious Revolution in 1688 prompted another crisis. As well as the Catholics in the country being dismayed by the overthrow of James, the Church of England was split. Many of the clergy refused to swear allegiance to William and Mary and their successors despite their antipathy to Catholicism. They felt legally bound by their previous oaths of allegiance to James – evoking the divine right of monarchs to rule and regarding the Revolution as an offence against God and the Constitution. Nine English bishops and 400 of the clergy refused to swear the oath and were deprived of their sees and livings, they became known as ‘Nonjurors’ (from the Latin verb juro ‘to swear an oath’). These Nonjurors and their supporters did not necessarily support the movement to restore James to the throne – the ‘Jacobite’ movement (from ‘Jacobus’ the Renaissance Latin form of James). Most Nonjurors and Jacobites were Tories, although there were ‘Whiggish’ Jacobites who saw William as a greater threat to liberty than James. Adding to the eclectic mix of those doubting the legality of the ascension of William and Mary to the throne were some religious nonconformist sects, in particular the Quakers, although most nonconformist groups supported the new government for good reason: the Toleration Act of 1689 allowed nonconformists their own places of worship and teachers as long as they pledged allegiance to the new order.

Tewkesbury was divided over the question. The town had a long tradition of religious nonconformity; it was said in 1676 that three-quarters of the population did not pay allegiance to the Church of England. The election of 1689 was reported as a ‘long and severe contest’.9 On the other hand, in 1691, William Colley of Tewkesbury, a labourer, when appearing at the Assizes, confessed to having said “There is no king in England but King James. And where is one for King William there is two for King James in England if there were occasion”.10 The nonconformist makeup of Tewkesbury probably helped to ensure the return of Richard Dowdeswell11 and Sir Francis Russell, both regarded as Whigs, who were in favour of the new Protestant king and queen. Tewkesbury continued to return Whig MPs to Parliament, including Henry Ireton12 in 1707, the grandson of Oliver Cromwell. Such was the Whig’s hold on the town that Daniel Defoe, shortly after the 1705 election described Tewkesbury as “a quiet trading drunken town a Whig baily and all well”.13

Nevertheless, there was a brief setback for the Whigs from 1710-1713 when one of the two Tewkesbury seats was held by William Bromley, a Tory barrister.14 Ireton won the other and William Dowdeswell15 lost out. Bromley was elected after a fractious campaign; five days before the poll, he wrote to a friend that “there will be here as great a struggle as has been known, the two old Members waiting against me and the corporation using all tricks”.Properties were temporarily bought for the purpose of increasing the number of freeholders’ votes – a house was purchased jointly by eight ‘furious Whigs’ from Bristol to enable them to vote. Twenty-two of the twenty-four members of the Town Council were for Ireton but the ‘Commonalty’ were heavily for Bromley who, during his campaign, had used Henry Sacheverell’s portrait and, when he set out for London to take up his seat, had it carried in procession before him “the bells ringing, and the people crying God bless the Queen, the Church and Dr Sacheverell”.16

to Expand

The sermon was published and achieved massive sales. He was subsequently impeached by the House of Commons (Tewkesbury MP, Henry Ireton voted in favour) on a vague charge of ‘high crimes and misdemeanours’, tried by the House of Lords, and banned from preaching for three years. He became a popular figure in the country and in response to his prosecution there were several riots around the country where the meeting-houses of nonconformists were attacked – many burnt to the ground. Sacheverellite sentiment is credited with contributing to the Tories landslide victory in the 1710 General Election. After his three-year ban, Queen Anne granted him a wealthy parish in London.18

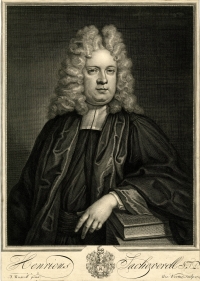

In his controversial sermon, Sacheverell described dissenting academies as places where “all the Hellish principles of fanaticism, regicide and anarchy are openly professed and taught”.19 One such dissenting academy was in Tewkesbury. These establishments provided educational opportunities to nonconformist Protestants, Quakers, Catholics and Jews as it was not possible to gain admission to the universities unless you were a practicing member of the Church of England. The Tewkesbury academy was housed in what is now the Tudor House20 at the north end of the High Street – the childhood home of the Tewkesbury author John Moore. The academy was run by Samuel Jones, and its students included dissenters and some Anglicans such as Thomas Secker who went on to become Archbishop of Canterbury. Jones had moved the academy from Gloucester in 1713 after being brought before an ecclesiastical court charged with keeping a private unlicensed school and teaching his students ‘seditious and antimonarchical principles’.21 These were commonly used charges and tactics employed by the established church against such non-conformist institutions throughout the country.

[Image is an engraving by George Vertue 1714 ©Trustees of the British Museum]

When George of Hanover became heir to the British throne it was clear that Queen Anne only had a short time to live; George quickly prepared a Regency Council list of Whigs to replace the Tory administration upon his accession. Anne died on 1 August 1714, the members on the new list of regents were sworn in and George was proclaimed King of Great Britain and Ireland. Due to weather problems he did not arrive in England until 18 September; he was then crowned at Westminster Abbey on 20 October. His coronation was accompanied by rioting in over twenty towns in England, disrupting celebrations of him becoming king. The disturbances were not directly Jacobite, more Sacheverellite and in support of High Church and the Tories, many thinking that the Catholic religion of the Old Pretender was preferable to the Lutheranism of the Hanoverians. The Tory gentry tacitly supported the rioters by staying away from the coronation festivities and in some instances joining in with the rioters’ proceedings. “Sacheverell … and damn all foreigners” the crowd cried at Bristol; at Taunton, “Church and Dr. Sacheverell”;at Birmingham, “Kill the old rogue [King George] … Sacheverell for ever”;at Shrewsbury, “High Church and Sacheverell for ever”. As in 1710 a number of nonconformist meeting-houses were badly damaged.22

The riot in Tewkesbury on coronation day included an attack on the Tewkesbury dissenters’ academy with the rioters shouting pro-Sacheverell and anti-roundhead slogans. The reference to ‘roundheads’ perhaps partly aimed at the memory of the late Henry Ireton (Oliver Cromwell was compared to George I in Jacobite pamphlets) and to nonconformists in general who were still thought of as representing republicanism – regarded as a worse tyranny than ‘Popery’. The town’s two sitting MPs were William Dowdeswell, and Anthony Lechmere,23 both Whigs, both regarded as opponents of Sacheverellite views.

A report of the riot was requested by Secretary of State, Viscount Townshend. Edward Northey24 and Nicholas Lechmere25 (the latter, brother of Anthony, had been very active in the prosecution of Sacheverell in 1710) compiled a summary of events from affidavits “transmitted to us relating to a riot committed at Tewkesbury on the twentieth day of October being the day of solemnizing your Majesty’s coronation”.26 The report states that Samuel Jones had invited friends to his house to celebrate the coronation and prepared a bonfire to be lit before his house in the evening. Meanwhile, “… disorderly persons to the number of forty being bargemen, watermen and troughmen” went to houses in the town and demanded money to fund another bonfire to be made “at the end of Key Lane” [no doubt Quay Lane] for “Dr. Sacheverell and the King”.People reprimanded them for putting Sacheverell’s name in front of the King, “it should be the King if they would have it so” they replied, but they were still refused money as they did not specify which king, and “being told that Mr Jones would have a bonfire at Red Lane End, the rioters replied they would bring the Red Lane to the Key Lane”. The bonfire at the house of Jones was now alight and the mob arrived “… armed with clubs and sticks with nailes affixed to the end of them, crying then and during the whole riot which laste two hours, Sacheverell for ever Down with the Roundheads”. Family and friends of Jones were assaulted and beaten and fled into the house “for the savins of their lives”.Jones and another came out and offered the mob drink if they would desist, but “they fell upon him, beat him and took away his wig, broke his windows, and endeavoured to force into his house, declaring they would sett his house on fire”.At this point George Moore, senior Bailiff of the Corporation, arrived and ordered John Jeens, the Constable, to help him restore order – Jeens declined to do so. The rioters knocked down Moore “and gave him several wounds on his head whereby he lost a great deal of blood, and his senses for some time”. Several other people were also attacked without provocation and “almost every night since in the streets, there has been the cry of Sacheverell for ever – Down with the Roundheads”. Listing “the principal actors in the riot” as, “John Taylor, butcher, William Redwards, butcher, John Harber, Morrison Fletcher, Joseph Tyler, Thomas Tyler jnr, Francis Evans, Richard Pool, John Hayward, William Hayward, Edward Edgcomb, Thomas Cotton, Linhidge, Samuel Davis, Robert Wilkins jnr, John Granger, Grimmel, Waite, Edward Langley”;the report stated that they “deserve the utmost punishment the law can inflict upon them”.

[Image is an engraving, c1840. The home of the dissenters’ academy in Tewkesbury and scene of the 1714 riot. (R. Ross)]

However, the prosecution of those involved in Coronation Day Riots throughout the country was half-hearted and muddled. The government at first decided to try offenders in London not trusting local judges and juries, five were brought from Taunton but later released on bail. Seven rioters were tried by Special Commission at Bristol, but this seems to have prolonged disorders in the city and those who were convicted received relatively light sentences of three months imprisonment, one was flogged.27 On the 31 October Dr. Sacheverell indulged in some spin doctoring via a remarkable attempt to shift the blame from the perpetrators to the victims by publishing an open letter stating that:

The Dissenters & their Friends have foolishly Endeavour’d to raise a Disturbance throughout the whole Kingdom by Trying in most Great Towns, on the Coronation Day to Burn Me in Effigie, to Inodiate my Person & Cause with the Populace: But if this Silly Stratagem has produc'd a quite Contrary Effect, & turn’s upon the First Authors, & Aggressors, and the People have Express’d their Resentment in any Culpable way, I hope it is not to be laid to my Charge, whose Name ... they make Use of as ‘the Shibboleth of the Party’.28

I can find no evidence that the Tewkesbury rioters were punished, despite the Northey Lechmere report recommending that “it is highly necessary that the Said Offenders should be prosecuted with the utmost Vigour, for which end wee humbly propose that an information be exhibited against them in Your Majesty’s Court of King’s Bench”. One of the accused, twenty-year-old Morrison Hodges Fletcher married a year later and had several children baptised in Tewkesbury, he lived to his eighties and was buried there in 1776.29

The Tewkesbury academy and Samuel Jones himself did not prosper. Archbishop Thomas Secker, in his autobiography, reports that when Jones moved to Tewkesbury from Gloucester, “Here he began to relax his Industry, to drink too much Ale & small Beer, & to lose his Temper.” Secker left the academy in May or June 1714, some months before the riot, and presented Jones with a resignation letter that included “in plain but friendly manner, several of his Faults … which he received civilly”.30 Jones died at Tewkesbury on 11 October 1719 aged thirty-seven, and was buried in Tewkesbury Abbey between the Clarence Vault and the East Wall; the Latin inscription on his monument extols his learning, his knowledge of languages, religion and education. He was succeeded at the academy by his nephew, Jeremiah Jones, who relocated the institution to Nailsworth. However, it soon declined in size and reputation.

There were a number of Jacobite riots throughout England in 1715: during the general election of that year (January to March), the anniversary of Queen Anne’s accession day and William III’s death (8 March), on the anniversary of Anne’s coronation (23 April), on the birthday of George I (28 May), on the anniversary of the restoration of Charles II (29 May), on the Pretender’s birthday (10 June) and on several other days. Many meeting houses of dissenters were attacked and some pulled down – over 30 were attacked in the West Midlands and Lancashire districts alone. A picture of William of Orange was burnt at Snow Hill in London on 23 April and an effigy of Oliver Cromwell at Smithfield on 28 May. On Restoration Day the cries at the riots were for “A Restoration, a Stewart, High Church and Ormonde”31 along with ‘proclamations’ of James III. Other slogans at various times and places were “No Hanoverians, no Presbiterian government”, “down with the Roundheads, no Constitutioners” [members of the Whig Constitutional Club]. The widespread nature and severity of these riots prompted the government to pass the Riot Act which strengthened the powers of local authorities to deal with demonstrations, including the availability of the death penalty for rioters who refused to disperse when ordered to do so by a magistrate.32

The year 1715 culminated in a full-scale Jacobite rebellion. The Earl of Mar, angered by his failure to find favour with the new king, launched a rebellion in Scotland in the name of the Pretender, proclaiming him James VIII of Scotland and James III of England. Mar initially had great success; he took Inverness, Perth, Aberdeen and Dundee. On the 13 November he fought government forces led by the Duke of Argyll at the battle of Sheriffmuir but did not press home his advantage, withdrawing instead to Perth. On the same day a smaller Jacobite army, led by Mackintosh of Borlum, that had marched south into England, met English troops at Preston, Lancashire – the battle lasted two days before the Jacobites were defeated. James, the Pretender, landed at Peterhead, Aberdeenshire, in December, but by then the initiative was lost and further military operations achieved nothing. Early in February 1716 he and Mar sailed back to exile in France. The next significant period of Jacobite activity was in the 1740s, notably with the rebellion led by the ‘Young Pretender’, ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’33 in 1745 that ended in a crushing defeat at the Battle of Culloden. There were still attempts to revive his cause up to the time of his death in 1788 when Jacobite political culture came to an end.

References

- Said by Leonard Piddock, attorney, to an audience in Ashby de la Zouche in 1715, Nicholas Rogers, Crowds, Culture, and Politics in Georgian Britain, (Clarendon Press Oxford 1998) pp 55-56.

- ‘Act of Settlement’, Encyclopaedia Britannica, [accessed 26 Jun 2017].

- Mary and Anne were daughters of James II by his first wife, Anne Hyde. James by his second wife, Mary of Modena, who had eleven other pregnancies, only one other child survived to adulthood, Louisa Maria Teresa.

- Jeremy Black, ‘Sophia, Princess Palatine of the Rhine (1630–1714)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004, [27 Jun 2017].

- Edward Gregg, Queen Anne (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001) p 394.

- Derek Benson, The Tewkesbury Races, THS Bulletin 14 (2005) p 19.

- Sir Henry Capell, 1st Baron Capell of Tewkesbury, KB, PC (1638-1696), Tewkesbury MP 1690-1692, History of Parliament [HoP] [28 Jun 2017]. (All the following references to Tewkesbury and other MPs are from the same source: HoP)

- Sir Francis Russell, 2nd Baronet of Wytley (1638-1706) of Strensham, Worcs., Tewkesbury MP 1673-1689, HoP.

- Anthea Jones, Tewkesbury, (2nd edition, Phillimore, 2003) pp 80-81.

- Paul Kleber Monod, Jacobitism and the English People, 1688–1788, Cambridge University Press (1993) p. 255.

[I highly recommend this book to those wishing to learn more about grassroots Jacobitism.]

- Richard Dowdeswell (1653-1711) of Pull Court, Bushley, Worcs., Tewkesbury MP 1685-1887 & 1689-1710, HoP.

- Henry Ireton (c1652-1711) son of Lieutenant-General Henry Ireton by Bridget, daughter of Oliver Cromwell, Tewkesbury MP 1707-1710, HoP.

- ‘The Borough of Tewkesbury: Introduction’, in A History of the County of Gloucester: Volume 8, ed. C.R. Elrington (London, 1968), pp. 110-118. British History Online [28 June 2017].

- William Bromley (1685-1756) of Upton-on-Severn, Tewkesbury MP 1710-1712, HoP.

- William Dowdeswell (1682-1728) of Pull Court, Bushley, Worcs., Tewkesbury MP 1711-1722, HoP.

- ‘Parliamentary Constituencies’, HoP: [21 Jul 2017].

- Henry Sacheverell, The Perils of False Brethren, in Church, and State.

- W.A. Speck, ‘Sacheverell, Henry (bap. 1674, d.1724)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 [1 Jul 2017]; Henry Sacheverell, Wikipedia, [2 Jul 2017].

- Sacheverell.

- Once called the Old House, was built in 1546. The original timber building was refronted in brick in the early 18th century and then with mock-timbering in 1897, ‘The Tudor House Hotel’, THS Bulletin 3, (1994).

- Articles exhibited against Samuel Jones of the parish of St John the Baptist, Gloucester, 1712, Gloucestershire Record Office, GDR B4/1/1056.

- Monod, pp 173–178.

- Anthony Lechmere (1674-1720) of Hanley Castle, Worcs., Tewkesbury MP 1714-1717, HoP.

- Edward Northey (1652-1723), Tiverton MP 1710-1722, HoP.

- Nicholas Lechmere, 1st Baron Lechmere (1675-1727), lawyer and politician who served as Attorney-General, Tewkesbury MP 1717-1721, HoP.

- The National Archives [NA], SP 35/74/5, the document is dated 15 Nov 1714.

- Monod, pp 178-179.

- Monod, pp 177-178.

- Tewkesbury Parish Registers P329 accessed via www.ancestry.co.uk [16 Jul 2017].

- The autobiography of Thomas Secker, Archbishop of Canterbury / edited by John S. Macauley and R. W. Greaves. Lawrence, Kansas: University of Kansas Libraries, 1988.

- James Butler, 2nd Duke of Ormonde (1665-1745), one of the most powerful men in the government of Queen Anne, lost his position on the crowning of George I and became a leading Jacobite, charged with treason and fled to France in 1715, [23 Jul 2017].

- Monod, pp 180-192.

- Charles Edward Louis John Casimir Sylvester Severino Maria Stuart (1720-1788), grandson of James II.

- James Bennett, The History of Tewkesbury, Cappella Archive Edition 2002 p197-198. (James Bennett (1785-1856) bookseller, Freeman and historian of Tewkesbury.)

- ‘Journal of a Gloucestershire Justice, A.D. 1715-1756’, Law Magazine and Law Review, xi, 1861, p 128.

- National Archives, SP 35/40 f.1789, [20 Jul 2017].

Comments