The Tewkesbury Bread Riot of 1795

to Expand

to Expand

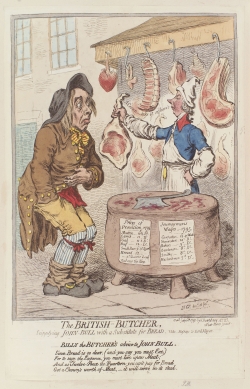

During 1795 and 1796, the shortages, high prices and profiteering practices led to many food related disturbances throughout the country; they very often involved women. Tewkesbury’s ‘bread riot’ occurred on Tuesday 24 June 1795. Flour was waiting at Tewkesbury Quay to be transported by water to Birmingham where no doubt a greater profit could be made than in Tewkesbury. On the following day, Henry Fowke, the Town Clerk of Tewkesbury, wrote to the Home Secretary, Lord Portland, reporting the event. This letter was one of scores that Portland received that year from all parts of the country reporting disturbances, asking for flour supplies or anticipating the need for military support.

My Lord

I do myself the Honour of addressing Your Grace on the subject of extreme Rioting at this place yesterday. Several Quantities of Wheaten Flour were forcibly taken out of the Barges at the Quay & carried off by divers Persons, chiefly Females – The civil force was convened with all possible Dispatch, & after much difficulty & confusion, the Riot was suppressed, & the ringleaders committed to the county rather than the Borough Goal, as more secure – The appearance of the Town this morning, I have the pleasure to say, is pacific. I have thought it my Duty to acquaint Government, through Your Grace, of this transaction. With the greatest respect, I am My Lord, Your Grace’s most obedient servant

Henry Fowke

Town Clerk of the Borough of Tewkesbury

Tewkesbury 25th June 1795 [6]

Clearly the Tewkesbury authorities thought it possible that attempts might be made to free those arrested from the town gaol, so they were sent to Gloucester. Those detained were all women and the city’s gaol register[7] records the details of the charges and names four of the prisoners.

Hester Macmaster aged 21, Mary Aldridge aged 16, Sarah Kinson aged 16, Ann Mayall aged 22. Committed the 24th of June 1795, by J. Wall, Esq; charged on the oaths of Henry Welling, William Moore, Charles Moore, and John Mew, of the borough of Tewkesbury, housekeepers, with having riotously and tumultuously assembled, with divers other persons, on the 24th of June instant, within the parish of Tewkesbury aforesaid, to the terror of his Majesty’s subjects, and in breach of the peace – Committed for want of sureties for their personal appearance at the next General Gaol Delivery, to answer the said charge.

A fifth woman accused was Happy Fielder; she was not committed until shortly before the trial in late July. It is possible that she may have managed to have had bail raised for her, or perhaps the degree of her role in the riot came to light later, or maybe she had evaded arrest.

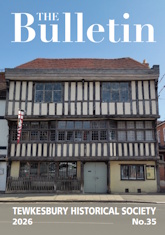

[Illustration: Tewkesbury - The View from the Quay in 1804 from The Book of Tewkesbury, Kathleen Ross 1986]

to Expand

to Expand

[Illustration: County Goal, Gloucester, 1790s © Glos. Archives]

Sentences of six months that the women received were actually very mild in the context of other trials of bread rioters both locally and nationally during 1795. Being female did not provide leniency: Margaret Boulker was hanged at Warwick for her participation in an attack on James Pickford’s steam flour mill at Birmingham in June. Two men were also shot dead by troops during this disorder.[15]

"I have great reason to be apprehensive of a visit from the Colliers in the Forest of Dean, who have for some days been going round to the Townes in their Neighbourhood, & selling the Flour, Wheat, & Bread belonging to the Millers & Bakers, at a reduced price."

to Expand

"Many plans are laid, and schemes proposed to keep our poor from perishing for want of bread; but alas! ... I doubt whether it be any charity, except to ourselves - to prevent their rising and knocking us on the head." Extract from a letter dated 29 Sep 1795 published in the Gentleman's Magazine, vol. 65, Part 2, p.824 (1795).

Comments