Ways and Means

Man has always made paths; even in prehistoric times he wore hunting tracks as he pursued his quarry, and the many Neolithic sites and burial chambers which survive today are a guide to the earliest tracks. Stonehenge was built before the Bronze Age began, and it is conceivable that Salisbury Plain, and the Stonehenge area in particular, was the centre or hub of several ancient ways, being equidistant from the south coast and such long distance roads as the Fosse Way and Icknield way.

The Romans built solid roads in straight lines connecting their forts, with posting stations in between, the forerunners of the coaching inns. The forts were usually a day's march apart, that is about fifteen miles. They also used the roads or tracks which had in use in the early Bronze Age, the Ridgeways, which ran along high ground and so could not be used when conditions were harsh, when the summerways were used instead, as they were lower down. Holloways were used in summer also; paths which had become 'hollow', or lower than the surrounding ground, through constant wear, and soil erosion by water flowing from the upper levels. Some still exist, such as those used today on the way up Cleeve Hill.

The increase in trade following the Norman Conquest and the building of abbeys and monasteries made more roads necessary. The few bridges built by the Romans had decayed, and as the abbeys needed bridges to market their produce, they contributed to their construction. They were not so willing to help with maintenance, however, but overcame this by making the giving of labour or cash part of the penances they meted out!

to Expand

The Long Bridge at Tewkesbury was built by King John with wood from his hunting estate; brushwood was laid on the marshy ground, and on this tree trunks of uniform size were placed. The bridge over the river which we now know as King John's Bridge was made of wood and stone. The King gave the tolls of the Wednesday and Saturday markets for its maintenance.

In 787 it was decreed that no church should be consecrated without a relic, and from then until the Dissolution pilgrims travelled the various ways. This led to the establishment of lodgings or hospices managed by the lay brothers. The Abbey hostelry on the present 'Bell Inn' site was one, and others included the 'New Inn' at Gloucester, for pilgrims visiting the tomb of Edward II, and the 'George' at Winchcombe for travellers to St. Kenelm's Well and Hailes Abbey.

Pack horses were recorded in the 1300's but they had certainly been used before then, for they could travel over the most difficult terrain, and could ford most streams. More bridges were built, usually narrow and humped with parapets low enough to allow packs to pass over the top, while longer bridges had recesses to allow pedestrians a refuge if they should encounter a train of packhorses. Some well-known modern businesses started as carriers. Bass started in this way in the 1720's, selling ale as a sideline. Inns were established along the routes to give shelter to the packmen; the names 'The Packhorse' and 'Talbot', the name of the dog used by packmen, originated from those days. Rock salt came into use in 1670 and provided work for the packhorses along the Salt Ways, like that from Tewkesbury to Droitwich, or that from Winchcombe, which can still be followed.

Animals were driven in large numbers to the markets or fairs, like the Nottingham Goose Fair. The drove roads were usually green lanes along which cattle were driven, covering about twelve miles a day. Where roads had to be used there were usually wide verges. As with the packhorse roads, inns sprang up as resting places for the drovers. One such was the Lygon Arms at Broadway, a welcome stop for Welsh drovers before they climbed the hill to Stow-on-the-Wold. Turkeys were driven from Norfolk to London, starting in October, when the crops were cut and there was stubble in the fields, and when the muddy roads had hardened with the first of the winter frosts, with from 300 to 1,000 birds in a drove. There could be up to three hundred such droves in a season. Geese, too, were driven to Nottingham Goose Fair, but were first 'walked' through sand and tar to give them 'boots' to travel the roads. Daniel Defoe says that an enterprising person developed a cart with three or four storeys, 'putting the creatures one above another, by which invention one cart will carry a great number.....they drive with two horses abreast like a coach.....changing horses, they ride night and day, bringing the fowl up to a hundred mile in days and a night' to London.

to Expand

Many of these ancient tracks can still be traced and are often part of a long-distance footpath. Besides Salt Ways, Pilgrim Ways, Lead Ways, Iron Ways and Peat Ways there are the 'tramways', like those in Snowdonia, the tracks along which slate was carried from the quarries. Corpse ways, too, can be traced, and some are said to be haunted! They came into being because some parishes were so large that coffins had to be carried on horseback to a burial ground, in areas like Dartmoor and Cumbria. Many of the ancient ways have disappeared, as farmers have grubbed out hedges and taken the lanes and byways into their fields.

Tewkesbury had four public roads into the town to maintain. The Ashchurch road was called Saladines Way, and as it was constantly flooded it was raised on a causeway in the early 16th. century. The road going south divided after it crossed Holm Bridge, one part going towards Gupshill and Tredington, the other along Lower Lode Lane to Deerhurst and Gloucester. The road to the north was over the Long Bridge to the Mythe.

Until 1555 these roads were dependent on private funds from rich landowners, and from money left in wills for their repair. In a will of 1502 money was left for the repair of the road from the Mill Avon to Holm Hill, which confirms that in those days the road went down Mill Street and along the Abbey Granary Wall in what is now Victoria Gardens, leaving Church Street at the 'Bell'.

Because many roads had become little more than quagmires the 1555 Act made each parish responsible for its roads. By the end of Elizabeth I's reign wheeled wagons carrying weights of sixty or so tons, drawn by eight to ten horses, were causing so much damage that the parishes complained, and an Act was passed to limit the number of horses to five. Even this was found to be too many, and the number had to be decreased.

The increase in traffic continued to wear the roads, and so the first turnpike was set up on the north road from London in 1663. A second Act in 1693 authorised the setting up of barriers and collection of tolls to help towards the cost of maintaining the roads. The first Act in the county was for the repair of the two routes to London from Gloucester, by Crickley Hill and Birdlip Hill. Defoe in his 'Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain' mentions 'the road from Birdlip Hill to Gloucester, formerly a terrible place for poor carriers and travellers out of Wales.... is now very well repaired'. It was not until 1726 that the other routes from Gloucester came under the Act.

to Expand

Turnpike Trusts usually let the tolls by auction. The highest bidder collected the tolls, and either had to make up whatever had been agreed or keep the difference, if he collected more. As today, financial mismanagement and apathy led to hostility among road-users, who were paying for little improvement. Farmers in Gotherington and Bishops Cleeve could not use carts to bring stock to market in Tewkesbury because of the poor state of the roads, and had to resort to pack ponies. Poorer people objected to paying tolls, and many toll-gates were destroyed and the collectors attacked. In 1734 men were hanged in Gloucester for destroying turnpikes near Tewkesbury.

It was not only travellers who were offensive. In a letter to the Gloucester Journal in September 1789 a complaint was made, that the writer in common with others had experienced 'insolence and imposition' from a Turnpike on the Tetbury-Bath road.

Richard Dowdeswell of Forthampton, an M.P. for Tewkesbury, opposed the 1726 Act for this area, because he was afraid turnpike tolls would make travellers less willing to pay the fares on his ferry at Lower Lode. Samuel Rudder wrote that he saw in the winter of 1776 a chaise mired in the Turnpike Road between Gloucester and Bristol, and was told that a horse had been smothered in the same place two days before, but luckily had been saved by some persons accidentally coming to the poor animal's assistance.

Nevertheless, roads did improve, although in some cases it took many years. Sometimes the original packhorse road was bypassed, and sometimes a road was lowered by making a cutting, as happened on the Gloucester-Chepstow road near Newham, and on the road over the Mythe. Bridges, too, were built where only fords or packhorse bridges had existed. The Halfpenny Bridge over the Thames at Lechlade, built in 1792, is a fine example, despite the fact that the architect was the keeper of the Oxford Gaol. East and West Looe were joined with a stone bridge of fifteen arches in the early 1700's. Barnstaple Bridge was built by a Londoner who traded from the town and became wealthy, and so in gratitude built the bridge.

In 1792 a 'Road Club' was formed by the principal landowners, gentlemen and yeomen of the Tewkesbury area. They had for years contributed large sums for the repair of local roads, particularly the Ashchurch road, which had long been neglected and had become impassable. The Road Club could instruct surveyors and compel parishes and individuals to discharge their obligations. The local stone was considered too soft for a durable surface, so harder stone was brought from quarries on the Avon at Bristol, and from the Wye, near Chepstow and Tintern. This became one of the principal cargoes of the Severn trows.

Consequently road surfaces improved, but which of the two contemporary road builders was the better is open to argument. Telford advocated a good base, as on the Mythe Road Bridge, with a camber, whilst John McAdam relied on the strength of the surfacing.

About the time as the Mythe Bridge was built, in the 1820's, the road north was re-routed to go over the Mythe Hill, instead of round the Tute, following a line along the Severn. Much of the old road has vanished, but in his account of his journey from Tewkesbury to Worcester Daniel Defoe says, 'all the way along the banks of the Severn....we had a pleasing sight of hedgerows, being filled with apple trees and pear trees and the fruit so common, that any passenger as they travel the road may gather and eat what they please.' The Worcester road over the Mythe was changed several Times; after the 1825 re-routing it went down Paget Lane and then followed the Severn route, except when it was flooded, when it crossed Shuthonger Common, along roughly the line of the present road. It was turnpiked at the junction with Paget Lane. At one time this road passed near Twyning, and then turned west over Brockeridge Common to Ripple Field.

The Tewkesbury to Gloucester road was changed from its route through Tredington, following the line of the Swilgate, and on to Deerhurst Walton, to a route further west of Tredington, by-passing Deerhurst. The old route went down Lanket Lane, which since the development of Perry Hill into a caravan park in about 1972 is no longer visible. The alternative way, called the Lower Way, beside the Severn to Deerhurst, was often flooded. It was described as a bridleway, traces of which can be seen today, and was included in the Tumpike Act. The inhabitants of Deerhurst were responsible for the upkeep of this road, and as the expenses were very heavy, keeping the banks of the Severn in repair to prevent the bridleway from being 'overflowed', they were 'exempt from Toll at the gate erected at such Lower Way'. In the meantime Mr. Dowdeswell managed to persuade Parliament to insert a clause into the Turnpike Act, exempting from tolls all persons who crossed his ferry at Lower Lode on their way to and from Tewkesbury.

Deerhurst seems to have been unfortunate with the upkeep of roads. It was expected to keep Hoo Lane in repair. To quote Bennett, The reparation of the Hoo Lane which leads from the Gloucester Turnpiked road to Deerhurst, occasioned an expensive law-suit at the Michaelmas county sessions in 1812, when the Parish of Deerhurst was ordered to repair it. The road to Tredington from the Gloucester road caused much dispute between the two parishes. Tredington insisted it belonged to Deerhurst, which was strongly denied. In consequence the road deteriorated so much that the Turnpike Trustees repaired it and erected a Tumpike gate where it joins the Gloucester road. Elm trees were used as markers in the Acts' descriptions of roads to be turnpiked, e.g. Isabel's Elm in Ashchurch, Oxenton Elm, Woodstone Elm and Piff's Elm. During the dispute over the turnpikes at Wooton-under-edge in 1749 an elm which had stood there for more than a hundred years was cut down and burnt by protesters.

Many toll houses have now vanished. There was one at the end of High Street by the Black Bear, another on the Mythe Hill, near Paget Lane, and one in Barton Road near Chance Street, by the Pound Garden, and one at the Hermitage, at the corner of Lower Lode Lane. There are still three to be seen around Tewkesbury; one by the Telford Bridge, another on the corner of Walton Cardiff Lane, and the third opposite Shephard's Mead on the Gloucester road.

of Gloucestershire, c 1826Click Image

to Expand

The market tolls were insufficient to keep the King John Bridge in good repair, so in 1621 Sir Dudley Digges applied to Parliament for an Act to compel the County to repair it. He was unsuccessful. In 1638, however, in the reign of Charles I, the Court ordered the County to repair it, on condition that the Borough would take responsibility for its upkeep. In 1747 the four arches over the Old Avon had to rebuilt, and in 1783 further repairs were made on both the bridge and the causeway. In 1810 it cost the parish over £1,000. The nine penny rate imposed was insufficient, and a fine of £600 was imposed by Gloucester Assizes, making another rate necessary. In 1823 it was proposed to repair and widen the bridges, but the cost of £1,700 was found to be too much. When the Mythe Hill road was lowered in 1824 the displaced soil was offered for the raising of the causeway. The inhabitants of Tewkesbury agreed to a penny rate. The Catholic Church built beside the old road, closed in 1827, shows how steep the hill used to be.

Tewkesbury was responsible for seven bridges which cost a considerable sum to maintain, because of frequent damage from floods. Some were only footbridges, two over the Swilgate, but still needed constant repair. During the Civil War there were two drawbridges. One was Holm Bridge. This remained so until 1635; it was repaired in 1750, widened and raised in 1756, and again in 1827. Gander Lane bridge was recorded as wooden in 1540, when it was called Priest's Bridge. It was replaced by a stone structure in 1791. The King John Bridge was widened from twelve feet in 1836. It was again rebuilt and widened to its present width in 1958.

An account in the Gloucester Journal of March 1774 tells of a man, returning home from Worcester, being blown, horse and all, in a violent storm from the Long Bridge causeway into the floodwater. Fortunately, both he and his horse were rescued.

Before the Mythe Bridge was built in the 1820's the Upper Lode ferry was used to cross the river; during the 17th. century it was called Over Lode. The farmers used the ferry to go to market, and payment was collected after harvest in the form of 'Thrave', which was 24 sheaves of corn, or a 'Thrass', twelve sheaves, according to the number of beasts likely to be carried, Some of the smaller farmers objected, especially when they had not used the ferry as much as expected. These tithes were stored in Passage Barn, near Bushley Parsonage.

The beginning of the coach era brought many changes to Tewkesbury. The Paving Act of 1787 improved the town as well as widening the streets. Church Street, at what we now know as the Cross, was very narrow, so to enable coaches to turn into High Street and Barton Street the Tolsey was demolished. Gloucester road was changed, too. It had previously left Church Street at the Bell, going down Mill Lane and along the Granary Wall into Victoria Gardens. Five houses at the Abbey end of the Merchants' cottages were demolished, and the road followed the present route.

The Act also improved the condition of the streets. Signs and other emblems had been used to denote trade or occupation; now all signposts, bow windows or projecting windows, stall window shutters, porches, post rails and other encroachments had to be removed if they projected more than eight inches from the street frontage. Rainwater had to be led from the roofs into gutters and downspouts, and thence into drains rather than onto the pavements. Noisome and offensive pigsties were to be removed from the side streets, and it was forbidden to throw rubbish into the streets. Slaughtering in public ways and the display of meat in the open was also forbidden. The deep gutter which ran down the centre of each main street, and the minor ones from the alleys which joined it, were considered dangerous, so the streets were cambered and iron gratings and culverts were introduced to the sides of the pavements. Some of the cost of this work was covered by the ratepayers, but householders had to pay the contractor when a pavement was laid outside their property.

The Turnpike Trusts soon realised that the increase in the number and type of wagons was ruining the streets, so a general Act of Parliament in 1753 attempted to limit the weight carried and the width of the wagon wheels. Tewkesbury even tried to make local hauliers replace their wheeled vehicles with the older dray sledges. The paving Act required wheels or runners to be flat, with no protruding nails, rivets or stubs. A weighing machine was also set up. In 1779 the Government imposed a tax on post horses and carriages.

In 1784 John Palmer of Bath had the idea of using coaches instead of postboys for mail. They would carry armed guards, and so would be less likely to be robbed. One postboy fell with his horse into a hollow filled with snow, near Fairford; with the greatest difficulty he disengaged himself and walked to Fairford, where he procured assistance to dig his horse out of the snow. This was the cause of the post being late last Monday,' says a report of the incident in the local paper.

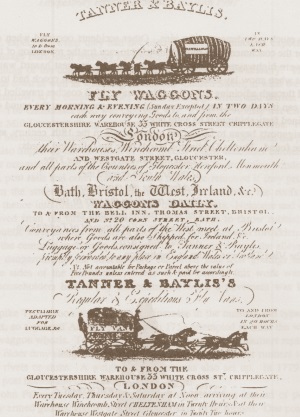

Wagons and coaches made travel easier and quicker. In the 1720's covered wagons with four or five horses pulling took four or five days to go from Gloucester to London. Accommodation was needed for the travellers and stabling for the horses, so the coaching inns came into their own, bringing work and trade to the towns.

By the 1820's more than thirty stage coaches a day were passing through Tewkesbury. The Swan and the Hop Pole were the largest inns, but the smaller ones also benefited. Hamlets were formed where an inn offered accommodation, or when a blacksmith or wheelwright set up business. This may have happened at Birdlip.

An advertisement of May 1807, announcing the sale by auction of the Swan Hotel, says, for many years past it has been highly celebrated for its Posting business....Tewkesbury is a large and populous town situated on the Great Road from Hollyhead, Liverpool, Birmingham and Worcester, to Gloucester, Cheltenham, Bath, Bristol and the West of England, and being surrounded with good roads.....an Inn of the first rank'.

Another notice of 1745 said: 'John Restell, carrier who now keeps the Pack Horse Inn, near the Market Place in Tewkesbury (where all the Gentlemen, tradesmen, etc. will meet with good accommodation) has fixed his stages for Pack Horses'. The notice goes on to give various destinations, and then continues, 'performed with good able horses, (if God permit) by me'.

Journeys in the first half of the 18th century were always advertised as 'performed if God permits', for they were long, arduous journeys, but by 1765 the roads had so greatly improved that the 'Gloucester Double Post Coach" could make the journey to London in twenty-one hours, for the price of £l.3s., with outside passengers and children in lap paying half-price. The luggage allowance for an inside passenger was fourteen pounds.

In December 1777 J.Chambers of Tewkesbury announced that the Tewkesbury, Oxford and London Flying Stage Wagon will set out early every Monday morning from the Maidenhead Inn, in Tewkesbury and get to London early Friday morning'. He lists various places on the route, and then adds, The Flying Stage Wagon will not be so long on the road by two days as the old Stage Wagon'. The Maidenhead could have been in Barton Street, but where was the Pack Horse Inn?

With the increased traffic on the roads accidents were inevitable, though many could have been avoided. Waggoners or coachmen, through the rivalry of their bosses, often fell asleep, and some took too much refreshment at the inns. Other accidents occurred when one vehicle tried to pass another, or the coachmen from rival firms tried to race for the reputation of their employers.

to Expand

There were highwaymen and footpads, too, but the greatest hazard was the weather. One report says that when snow lay to a considerable depth the London coach had to leave the turnpiked road and travel through adjoining fields for a short way. Mail coaches travelled free through the toll gates, and one can imagine the turnpike man rushing to open them at the sound of the post horn, for fear of being fined forty shillings if he were late! Handposts or signposts began to be erected at crossroads in the 18th. century, and many interesting ones can still be found. That at Teddington Hands bore the following words:

Edmond Atnvood of the Vine Tree

At the first time erected me,

And freely he did this bestow

Strange travellers the way to show.

Ten generations past and gone

Repaired by Alice Attwood of Teddington.

August 10th. 1876

There was another signpost at the Cross Hands just below the crest of Broadway Hill, from Stow-on-the-Wold. It has four gaunt iron hands on which are written:

The Way to Warwick

The Way to Woster

XXIIII Miles 1669

XVIII Miles NI

The last two are the way to Oxford and the way to Gloucester. The post was erected by one of the Izods of Campden in 1669, and local tradition has it that the iron spike at the top was used to impale sheep-stealers and other robbers!

The coming of the railway started the decline in the coaching trade. Tewkesbury eventually had a branch line, but by then the damage had been done and the town also started to decline. We can now travel from one end of the country without going through large towns, passing over rivers on large bridges or along raised roads that would have been thought impossible to build only a few years ago.

Comments

Wednesday 3-Jul-2024 by: Bruce Smith

What a great article.

Cynthia, I would love to ask you a question: is there evidence of drovers from the west who had forded - or been ferried - across the Lower Lode have taken the path through Bloody Meadow to Lincoln Green and then joined either the Stow road towards Stanway or else gone east to Gotherington & over Nottingham Hill?

It's probably an impossible question to answer, in which case, sorry.

Thanks again

Bruce

Monday 10-Jun-2024 by: Bruce Smith

Didn't mean to wipe out last comment!

Have realised, after looking through old notes, that I talked to the owners of Corner House Farm in Forthampton nearly 10 years ago and was told that it used to be a drovers' inn.

Later I found that the river was often fordable at the Lower Lode - as well as the Upper - before they dredged it for grain barges in the 1850s (?)

Back to Forthampton, then!

Saturday 8-Jun-2024 by: Bruce Smith

Liked this page very much. Beautifully set out.

I had not realised that the Lower Lode was, till 1726, used to ferry passengers across to Tewkesbury. From Wales, maybe?

Bruce Smith

Ferryside

Carmarthen