Tewkesbury's Flour Mills

The Abbey or Town Mills

to Expand

Like many water mills, Tewkesbury’s can claim to be mentioned in Domesday Book. Two mills were part of the large manorial estate which in 1086 was held by King William. Shortly afterwards, the manor of Tewkesbury was granted to a faithful Norman baron, who in turn in 1105 endowed his newly-founded Benedictine abbey with two corn mills, and it is clear that these two mills, which continued in the abbey’s possession until its dissolution in 1540, were side by side on the Mill Avon. Maps of Tewkesbury show how the rivers almost surround the town and the site of the Abbey’s mills on its south side. At some time, presumably before 1086, a long cut was made which linked the Avon and the Swilgate; the cut is now known as the Mill Avon but often in the past was called simply the Avon.

The name itself is a fruitful source of confusion. The cut necessitated construction of a weir in the Avon close to its confluence with the Severn, where the flow is considerable, and the creation of canal banks to hold the water at a higher level than the land lying to westwards. A great deal of surplus water poured over the weir into the Stanchard Pit and continued past Tewkesbury Quay to the Severn. This arm has always accurately been called the Old Avon.The weir blocked navigation above Tewkesbury Quay, with the result that cargoes transported on the Severn had to be transhipped at the Quay onto the Mill Avon for destinations like Evesham and Stratford higher up the Avon. After turning the mill wheels, the water flowed into the Swilgate and thence into the Severn, while a bypass channel carried surplus water past the mills. It should be noted that the cut followed closely the contour of the slightly higher ground along which Tewkesbury’s main streets ran. To the west of the town is the great meadow or ‘Ham’, which frequently floods. A big flood covers the banks of the Mill Avon and joins it to the Severn in a great sheet of water, which completely surrounds the mills.

There are not many medieval references to the Tewkesbury mills, but some are rather puzzling. In 1211 ‘the mills of the town’ were referred to as belonging to the honour of Gloucester.[3] As the Lord of Tewkesbury was also the patron of the abbey, this must explain the reference. Only a windmill was mentioned in the Inquisitiones Post Mortem: enquiries that were held into the estates of the earls of Gloucester on their deaths. The purpose of this procedure was to establish the extent of an estate held directly from the king, and who was the rightful heir; these were held in Tewkesbury seven times in 80 years, between 1296 and 1375, as first De Clares and then Despensers died young.[4]

Probably there were two early medieval mills, each with a waterwheel, to which the abbey added a third mill which was a fulling mill. Two mills belonging to the Abbot of Tewkesbury were amongst the taxable assets of the church recorded in 1291, in a list prepared to help the king collect papal taxes; the tax had been assigned to Edward I for six years to encourage him to enter a crusade. Hence it is known as the Pope Nicholas Taxation or Taxatio Ecclesiastica. The same document recorded a fulling mill, the profits of which went to the abbey’s Kitchener.[4]

In 1535 another survey of church wealth, the Valor Ecclesiasticus, also recorded “Mills at Tewkesbury: two water corn mills at the end of the town of Tewkesbury situated on the River Avon occupied by the monastery” and worth £10 a year; in addition, £2 rent from ‘Barcocke’s Mill’ went to the Kitchener, which therefore seems to be the fulling mill referred to in 1291. There is no specific reference to a fulling mill after 1291; but in mid-16th century an important citizen of Tewkesbury, Giles Geast, was a clothier and mercer who owned looms and houses occupied by weavers, who had ‘Letters Patent’ granting the right to ‘seal’ cloths.[5] As there were many other trades associated with the cloth industry, a fulling mill might still have been in use. The woollen cloth industry declined in the 17th and 18th centuries.

The monastery’s extensive property was in the Crown’s hands following the dissolution of the abbey in January 1540 and a survey was prepared, written on many sheets of parchment. It included “all those mills formerly the abbey’s” which had been leased in June 1540, together with Tewkesbury Park, to Henry Jernyngham. This house, often called ‘The Lodge’, and the park had for some centuries been the centre of the royal manor of Tewkesbury; the Crown had leased this estate to the Abbey in 1504.[6] It was sold by the Crown in 1550. Sometime later there are leases of the mills by the owners of Tewkesbury Park; throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries this was a member of the Popham family. The mills were called the ‘Town mills’ in the description of the bounds of the borough in the charter of Elizabeth I to the town in 1575;[7] the name ‘Abbey Mill’ became fashionable in the nineteenth century. Towards the end of the sixteenth century, one of the mills was enlarged by adding a water wheel; by 1594 there were certainly four mills. Moreover in 1619 the Court of Sewers for the River Avon ordered the demolition of a fifth water grist mill, one of Sir Frances Popham’s five mills “being a great nuisance in the river”.

Four mills – that is four water wheels – survived on this site from 1616 until the present. Whether the physical layout of the mills altered before the late eighteenth century is not known. There is some indication that they continued to form two units; in 1694 Alexander Popham’s lease to Isaac Merrill and Joseph Blackborne bakers, referred to “all those three water corn mills being under one roof”[10]; the fourth mill was, therefore, probably separate. The first certain record of a reconstruction, in 1793, was reported by James Bennett, the historian of Tewkesbury who collected so much valuable information together: “Tewkesbury abbey mills were rebuilt by Mr Richard Jenkins, who placed therein eight pair of millstones which were worked by four large water wheels”.[11] He had purchased the mills and other property in the immediate area from John Wall, the husband of a Popham who inherited the Tewkesbury Park estate. The mills were from this time grouped into an Upper and a Lower mill. The first map of Tewkesbury, which William Dyde placed at the beginning of his History and Antiquities of Tewkesbury in 1790, shows clearly the footpath passing between the Upper and Lower Mills, giving access from Church Street and Mill Bank to the Ham.

Until the later eighteenth century, men were rarely described simply as millers; their stated occupation was either ‘baker’ or ‘maltster’, even though the production of flour must have been of significance in a town of about 2,000 inhabitants in mid-sixteenth century, rising to 2,866 in 1723 (an exact census). In 1575, when Tewkesbury obtained a royal charter of incorporation, 25 maltmakers, out of 245 whose occupations were given, were the second largest group amongst the first freemen of the borough. No wonder that, at the same date, inhabitants within the town were forbidden to make malt between the last day of May and the first day of September – barley must have been used to make bread flour at least before the new year’s harvest of wheat was available. Eight of the first freemen were bakers and probably one of the bakers was a miller, though this was not stated specifically.[12] Similarly, when a new town charter was obtained in 1686, the list of freemen included nine bakers, though only three maltsters. Richard Cooke, named in 1694 as the lessee of the mills prior to the new lease granted to Merrill and Blackborne, bakers, was described as a baker in 1672 and 1674 when taking an apprentice; on the first occasion it was his own son, which was a way of ensuring he became a freeman without extra payment. However, when Isaac Merill and Richard Cooke jointly signed a covenant with Alexander Popham in 1694, they were described as “millers of Tewkesbury”, as also were Joseph and John Blackborne in a similar document.

In the eighteenth century, milling appears to have been more often linked with malting than with baking. On the bank of the Mill Avon adjacent to the Abbey mills, there was a ‘great barn’ which had belonged to the abbey. This was adapted as a malthouse and, on occasions, was certainly occupied by the lessee of the mills; it was still marked as a malthouse on later 19th century maps. In 1757 William Mew the elder, for example, was a maltster, miller and flourman. He was one of eight men refusing to pay tolls to Tewkesbury Borough Council. It had the power to charge for corn loaded at the Quay or passing to and from the town over the Quay Bridge which crossed the Mill Avon; these tolls formed the major part of the Council’s income. Thomas Mew, maltster and dealer in corn and grain, along with Samuel Mew the younger, bargemaster and maltster, formed quite a family cartel in objecting.[13] A settlement was achieved and they agreed to make some payments to the Council, but tolls were again a subject of dispute in 1800.

Information on occupations becomes more common as Trade Directories began to be published and Bailey’s Directory of 1784 is an early example. It listed William Mew, ‘miller and maltster’, and he was one of only 27 men named in the Directory. (He was probably the younger William at the time of the tolls protest.) He was also a member of the Borough Council, a small self-selecting body of men. In the Borough rating assessment of 1780 and again in 1791 he was recorded as the occupier of the corn mills and land, rented of John Wall Esq., as well as a house and malthouse.[14] The mills, rated at £72, were considerably more valuable than any other property in Tewkesbury: the largest inn in the town, the Swan, was rated at £40 and only six houses exceeded £20. Where they have survived, rating lists, especially for the collection of money to support the poor (Overseers’ rates) are a particularly useful source of information on owners and occupiers.

An order of the local justices of the peace, in the period of exceptionally high corn prices in January 1802, gives an indication of the quality of flour made at this period. Bread for the next three months was not to be any finer in quality than standard wheaten bread: viz. made of the flour of wheat without any admixture or division, and was to be “the whole produce of the grain, the bran or hull thereof only excepted, and shall weigh three out of four parts of the weight of the wheat whereof it shall be made”. The order was repeated many times in the following few years.[15] An unusual source of information on the mills, and indeed on many aspects of everyday life in Tewkesbury, is the long series of notebooks, starting in 1800, of the local firm of Moore & Sons, Estate Agents and Auctioneers.[16] The 20th century novelist, John Moore, was a member of the family, and briefly worked in the family firm. In Portrait of Elmbury, a thinly disguised portrait of his home town, he described the premises at 46, High Street;

“The walls of this office – and indeed of every room in the building – were lined with books: books in red morocco bindings, several thousand of them, which contained the ‘Particulars of Sale’ of every property that had passed through the firm’s hands – almost every dwelling-house, in fact, every farm, smallholding, shop, pub, orchard and meadow within six miles of Elmbury.”

Valuations were recorded using various codes.

The first reference to the mills is dated 1807 and is a valuation of the effects of Michael Proctor, deceased. In the British Universal Directory of about 1790, he was identified as a maltster. The Upper Mill contained six pairs of stones; the Lower Mill five pairs. A small frigate and two other boats were included with the Upper Mill, with 38 bolting cloths; 23 bolting cloths and a house boat were included with the Lower Mill, along with pigsties, a cider mill house, a cow house, rick yard, brew house etc.. His dwelling house in Tewkesbury was large and well-equipped. He was also a farmer with cows, calves, lots of pigs, sheep, lambs, hay, five cart horses and all the implements of husbandry. It is interesting to note that his farming interests were worth over £7,000 – but the effects in the mills only £256.

A great deal of information is available on the estate of John Jenkins. In 1821 the stock in the malthouse was valued on being transferred from Jenkins and Butts to Mr John Jenkins. It included 100 bushel of malt, £40, 4 ½ sacks of flour, double ground, £13, and 4 sacks of bread flour, 23 ½ of meal and 2 of oats. Eighteen months later, in May 1823, a first sale of his property was held at the ‘Bell and Bowling Green’. The first item was “a stack of mills, the Abbey or Town mills”, with which was a pound of water a mile long. This described the Mill Avon from the weir above King John’s Bridge on the north side of the town to the Abbey mills on the south. The supply of water was said to be more than sufficient for the present machinery and a net income of £500 a year was taken from the grinding. The machinery was of cast iron of the “best construction”. The mills were “newly built”, and “admirably arranged”. The malthouse and counting house was “stone-built” and “very strong”, containing two kilns with a large leaded cistern and pump; the floors were well-laid and there was room on the site for eight tenements in addition to the very large malthouse. Jenkins also owned the Bell Inn, the Bowling Green to the rear, four cottages, stable, fold yard, cow stalls and a piggery on Mill Bank. To those who know Tewkesbury, this summons up a surprising picture of the rural nature of the area, which has now a neat row of houses facing the mill pond.

Despite the agent’s helpful descriptions, only the Bell was sold on this occasion, for £1,100. In September 1823, the sale of a number of mill items followed – bushels of excellent flour, a mahogany miller’s staff and an oak one, “a very capital malt bruising mill with a pair of six inch steel rollers, frame, hopper etc”, and 200 sacks. What were the 14 bushels of lime used for? In July 1824, this time at the Swan, the other properties were successfully offered for sale; the double malthouse went for £520 and Jenkins’ house for £840. The price of the mills is coded, but was perhaps £5,000. The final sale of John Jenkins’ ‘effects’ was in March 1825: the frigate of 20 tons, a fishing boat, a capital winnowing machine by Chambers, six dressing machines covered with wire, a capital malt mill, writing desk and stool and pigeon holes – a glimpse of an old-fashioned office. Mr Thomas Arkell had probably become the miller, as in 1826 he passed the mill stock over to Mr Joseph Bird. Soon after, the viability of the Abbey mills was challenged by the erection about 1830 of a steam mill on Tewkesbury Quay. It was a small enterprise but it pointed the way, introducing the potential for a quite different scale of operation that has continued to increase to the present day. However, the challenge was not yet clear.

One William Proctor was at the Abbey mills in 1839 according to a rating assessment, while he or another William continued there until 1858; John Stanton was the owner. It is an indication of the traps in statements in Directories that, while John Stanton was stated to be a miller in Tewkesbury in Slater’s Directory in 1852, in the Borough rating assessment he was the owner of the Abbey mills while William Proctor was the occupier. A table of wages for the week ending 17 March 1854 shows 17 men and 13 women who were ‘doublers’ employed in ‘Room C’; there was one engineer, one gasman, and one carpenter.[17] Seven men living in Mill Court or Mill Bank gave their occupation as ‘miller’ in the 1851 Census with one living in Church Street, as well as Samuel Healing and John Stanton. About 1854, the mills again underwent an extensive work of reconstruction on the upper or Pound side, “up to which time the approach to the Ham ran directly through the centre of the Mill”.[18] The path was diverted to the northern side, and is still in constant use.

A decade later, the much larger Borough steam mill was erected on the Quay. The scale of operation outclassed the Abbey mills, although still the latter continued to work into the 20th century. William Rice occupied the Abbey mills by 1881, and then William Rice and Co..[19] A large turbine was installed, despite two water wheels still being used to drive eight pairs of stones and to produce the mill’s electric lighting – which also supplied part of the town.[20] There was said to be a local demand for stone ground meal. Rice’s were entered in Kelly’s Directory in 1914 and 1923 as millers and corn merchants, with premises in High Street, the Quay and the Abbey mills. However, they were no longer in business in Tewkesbury in 1927. Before 1933 the mills had become a luncheon and tea room, though the water wheels were still intact. It was, in fact, the death of grindstone milling which finally stopped the Abbey mills.

The Borough Mills at the Quay

It is sometimes suggested, for example in the authoritative Victoria History of the County of Gloucester, that there were water mills on the Quay prior to the erection of a steam mill there about 1830. The history of Healing’s Mill (published about 1980) also assumes that the mills were located to make use of water power.[21] Water transport was certainly a factor in the siting of the new steam mill – but not water power. The Quay was close to the junction of the Old Avon with the Severn, being a scene of busy activity, particularly in sending malt and receiving corn and coal. To reach the Abbey mills, boats had to pass through the lock into the Mill Avon. The churchwardens’ rating assessment for 1839 noted a mill on the Quay occupied by Thomas Bluck; but in the overseers’ rating list of 1842 Thomas Bluck was the owner of a ‘steam flour mill’ at the Quay, making the situation clear, while Richard Proctor was the occupier.[22]

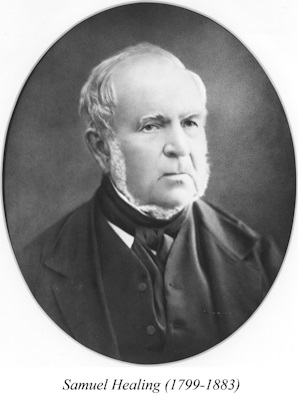

Meanwhile the Healing family had come to Tewkesbury. Samuel Healing, maltster, lived in Church Street in 1820. Samuel Healing and Sons were millers in 1852, the mills being at Strensham, north of Tewkesbury, and at Cox’s Mill, Evesham.

According to T.W. Hibbard in a later account of Gloucestershire flour milling, Samuel Healing took over the Abbey mills and the Quay Mills in 1858.[23] If so, he soon wished to increase the size of his operation in Tewkesbury. In the Register of 12 December 1863 there was an item headed “Board of Health. Proposed Improvements on the Quay” and it continued:

“Mr. Lewis (of the firm of Moore, Lewis and Moore) said he attended on behalf of Messrs. Healing, to submit to the notice of the Board, a work of great public improvement and importance. Messrs. Healing proposed to erect on the site of the warehouse, lately in the occupation of Messrs. Rice, just over the Quay Bridge, and leading towards the Locks, a large steam mill.”

Samuel Healing, the founder of the firm, was in his mid sixties and was one of the leading townsmen of Tewkesbury. His sons, William and Alfred, were in their early thirties and their names appear on an indenture of 1864 as taking possession of the site for the new mill from William and Michael Procter, whose tenant was Messrs. Rice. They acquired also a basin on the Old Avon where barges are moored; also there was a branch railway linking the Quay with the main Gloucester-Birmingham line.

Early in 1866 the paper reported that

“Messrs. Samuel Healing and Sons’ Borough Flour Mills are now completed and in operation. The mill building is 80 ft. by 40 ft., and contains 7 floors, all of good height. The whole of the works have been executed by Mr. W.H. James of Tewkesbury, who has furnished the designs and has had the sole charge and superintendence throughout. The mill contains 12 pairs of stones and the most approved description of machinery for elevating and cleansing the wheat and dressing the flour. The whole is driven by a MacNaught engine of 30 nominal horse power, supplied from two 30 foot double tubed boilers, seven feet in diameter.” [24]

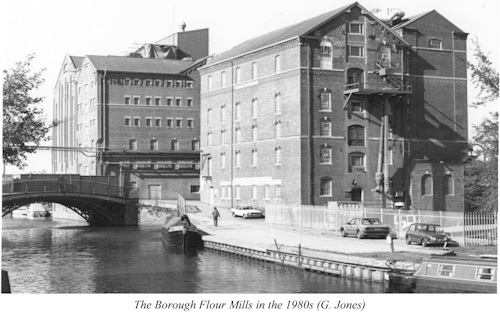

W. H. James was a partner in the firm of Collins and Cullis. The building was a handsome one of brick, with a prominent inscription Borough Flour Mills. The name was a nice variation from ‘Town mills’ which was the name used so often of the Abbey mills. A few years later, in 1874, a similar large storehouse was erected on the other side of Quay Lane; the building has long had a remarkable tilt, very obvious from the other side of the river: the brick courses which are not parallel to the water give the impression that the water runs uphill.

A flourmill with 12 pairs of millstones could have supplied a substantial market. For instance, with 2 pairs idle for stone dressing and the mill running for only 40 hours per week, enough flour could have been produced to supply 11,000 people at the rate of 5 lbs. of flour per person per week. As the population of Tewkesbury was at its maximum in 1861, 5876 – but then beginning to fall a little – the new mill had sufficient capacity to supply not only the whole town, but an extensive additional market. Healings’ site at Tewkesbury placed them in the category of ‘country millers’, compared with the increasingly important firms at the large ports. Economic milling became partly a problem of transport costs, so improved river navigation and good rail links were vital, to allow flexible strategies in wheat buying and flour selling. In the later 1850s nearly three quarters of the wheat available for consumption was produced at home while just over a quarter came from overseas suppliers. However, the pattern of wheat supply was gradually changing. In the early and mid 1860s, 40% was imported and the trend continued, spurred by rapid technical change in the milling industry; later in the century imported wheat made up nearly 70% of the total. Much of the foreign wheat was harder than English; the home-grown varieties produced bread of superior taste, but the foreign wheats gave stronger flours and bolder, well-piled loaves. The popular criteria had become appearance and economy.

Healings’ new ‘BoroughFlour Mills’ represented a major development, not only by their size in 1865 but, notably, for the technical changes introduced 20 years later. In 1885 Healings introduced Carter’s automatic roller system, thereby associating themselves with the more progressive millers in the country. Radical changes in British milling practice had begun in the late 1870s with successful experiments by Henry Simon of Manchester who became the leading milling engineer; next in prominence as consultant and contractor was Harrison Carter. Hard wheat, however, could not be milled effectively by millstones without producing large quantities of bran fragments. The problem was overcome by using roller mills, with pairs of chilled cast iron, fluted rolls to break open the grain. Roller mills were introduced particularly between 1883 and 1885, with another major phase of development around 1890. Smooth iron rolls were used to reduce the interior of the grain to flour and numerous designs of sieving and purifying machine were developed to separate components and eliminate the bran.[25] In the early and mid 1880s millstones were gradually replaced and, in the early 1890s, they became obsolete. Referring to the decay of the country water mills that had previously supplied the smaller towns and rural communities, T.W. Hibbard, principal of J. Reynolds & Company of Gloucester, observed in 1897 that “there is scarcely one now making flour for sale”. Whereas the small mills either stopped or survived on provender trade, Healings prospered and the tall brick buildings still dominate the view along the Mill Avon.

There was a major extension to the wheat storage building in 1889 with probable improvements in the main mill at the same time. Gardner’s 1891 Visitors Guide to Tewkesbury noted the “huge block of buildings known as the Borough Flour Mills. These mills are capable of turning out between 3,000 and 4,000 sacks of flour per week, being fitted with the most approved machinery, and lighted by the electric light”. A more accurate report was that the mills had a productive capacity of 25 sacks per hour.[26] In comparison, J. Reynolds & Company’s Albert flour mill at Gloucester then had a capacity of 20 sacks of flour per hour and Priday Metford’s City flour mills could produce 15. These were the three principal mills in the area. Gardner’s Guide in 1903 amplified the description:

“Messrs Healing’s Borough Flour Mills, which are fitted up with admirable modern machinery and lighted with electric light – a great desideratum in the interests of health – and which supply in a great measure the Midlands and South Wales with flour”.

The extent of Healings’ market ensured their survival in the fiercely competitive conditions of the English industry.

In 1892, the ‘Convention of the National Association of British and Irish Millers’ met in Gloucester. An excursion to Tewkesbury by river steamer was planned for one afternoon and Healing’s mills were open to visitors. The programme and account of the mills was published in The Miller on 6 June 1892. Healings’ silo a little further down the Mill Avon was said to hold 7,500 quarters of wheat. The next time a convention met in Gloucester was 1927. Once again members inspected the Tewkesbury Borough Flour Mills, by this date operating on the Simon ‘Alphega-Plansifter’ system, following remodelling in 1922.

“Practically all the foreign wheat used at the Borough Mills is brought along the Severn direct from Avonmouth and Sharpness, and the same route is used for the despatch of a large proportion of the finished products”.

Rail and canal transport routes were also used and a fleet of road wagons. The report in Milling on 11 June 1927 emphasised the cleanliness of the mill, and the high proportion of ‘top patents’ produced.

After a further remodelling in 1932, another account appeared in Milling on 10 June 1933. Messrs Simon had increased capacity to 30 sacks per hour. The perfect cleanliness of the mill and machinery “is an outstanding feature”. Steamers and barges brought corn to the mill and storage bins had a capacity of 10,000 quarters. The Woodhouse and Mitchell engine now developed 500 ihp. At the same time the business became a private limited company, S. Healing & Sons Ltd.

In 1961 the business was acquired by Allied Mills Limited and in the mid 1970s the mill was again remodelled, with the installation of a large new milling plant of the latest modern design. In 2003, Healings was bought by ADM of the U.S.A., the Archer Daniels Midland Company. Although the branch railway has gone and water transport is not important, Healings’ Mill is still well-sited for supplying inland markets, and continues to be an important business in Tewkesbury.

Acknowledgements

This article was first published in the Midland Wind and Water Mills Group Journal 22 (2003) and permission to reprint is gratefully acknowledged.

Photographs are by Glyn Jones, and I am pleased to record my gratitude for much help in assembling material on the flour mills of Tewkesbury.

Anthea Jones read Modern History at St. Hugh’s College, Oxford and obtained a doctorate at the University of Kent at Canterbury. She has been a lecturer in higher education and, for fifteen years, was head of history and latterly also director of studies at Cheltenham Ladies’ College. Her book, Tewkesbury, was published in 1987 and re-issued in 2003; The Cotswolds in 1994 and A thousand years of the English Parish in 2000. The Editors recognise her significant contribution to the early years of T.H.S.

References

- James Bennett, Tewkesbury (1830), p313.

- This article is a much-expanded version of the account in A. Jones, Tewkesbury (1987).

- Victoria County History of Gloucestershire (VCH Glos.) (8) assumes that there were both town mills and abbey mills at this date.

- The molendin’ follat is abbreviated from molendinum follatio (or fullatio); ‘follat’ should not be read as ‘sollat’ and so does not refer to the River Swilgate as was suggested in VCH Glos. (6) 139.

- Gloucestershire Record Office (GRO). Hockaday Abstracts 369/will of 1558.

- VCH Glos. (8) 132.

- Bennett 379-80.

- VCH Glos. (8) 139.

- National Register of Archives, Tewkesbury Park.

- GRO/D2957/302/56.

- Tewkesbury Yearly Register (2) 481.

- GRO/TBR/A1/1.

- GRO/TBR/A1/7/Jan.1757.

- GRO/TBR/A6/1 and P329/OV1/1.

- GRO/QT/SII.

- GRO/D2080/40, 271, 303, 313, 343, 402, 465.

- GRO/TBR/D7/9.

- W. North, Historic Tewkesbury, a ready guide-book for tourists and visitors (c.1904), 12.

- GRO/P329/OV1/15.

- The Miller 3 October 1910.

- Gloucestershire Countryside 1934-37, 29-30 stated that the Quay mill dated from 1830.

- GRO/P329/CW1/3 and TBR/A6/6.

- T. W. Hibbard, ‘Flour milling in Gloucestershire 1837-97’, The Miller, 3 May 1897, 190.

- Tewkesbury Register, 31 March 1866. The report was drawn from The Builder.

- See G. Jones, The Millers (2001) for a full account of this crucial period in English flour milling.

- A sack was 280 lb. of flour.

Comments