VJ80-2025: The Prisoners of War

It is not easy to separate the deaths of soldiers as a result of battle - or whether they were captured prisoners of war who were treated appallingly. At first, all that was known was that soldiers were “missing” in the Far East. Pte. Osborne was buried near Rangoon Jail, Burma; as this cemetery was only investigated in 1948: all we can do is “only hope that they were killed in action fighting the Japanese, rather than as POWs”.[1]

Some had already been shipped out to Hong Kong, which was the first colony to fall to the Japanese on Christmas Day, 1941 – Signalman Joe Wilkins became one of 10,947 Commonwealth POWs.[2]

A lot of luck was involved as thousands of experienced and well-trained soldiers – Hemming with experience of Dunkirk in 1940 and F.J. Jane in Egypt and Palestine. The former left Liverpool before Pearl Harbor. They arrived in South Africa, however, after that “day of Infamy”, the “lucky” ones found themselves sent to Egypt to fight - or die - in the successful North Africa Battles for which they were duly awarded medals.

| Name | Rank | Service | Place | Date |

| Hemming, Charles Donald POW | Private | Army | Forthampton | 20-Dec-1943 |

| Key, Frederick L. POW | Bombadier | Army | Tewkesbury | 03-Jun-1943 |

| Osborne, Lionel H. J. POW | Private | Army | Tewkesbury | 19-Mar-1942 |

| Ryland, Cecil POW | Private | Army | Tewkesbury | 03-Jul-1943 |

References

- J Dixon 2004

- See Information about Surviving OWs form, the Tewkesbury Register below

- https://windowseater.com/travel/thailand/the-death-railway/wampo-viaduct/

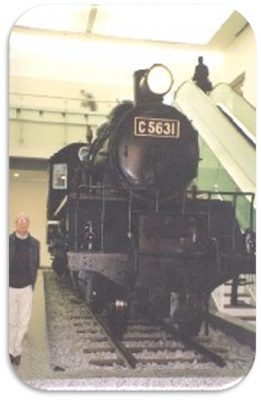

My visit to Japan in 2004

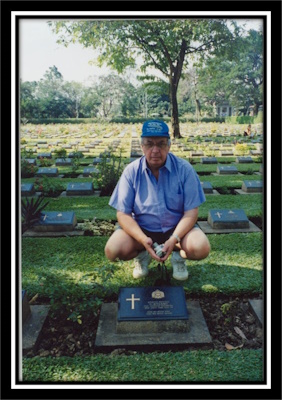

of Pte. Ryland in 2004Click Image

to Expand

POWs like Sapper Lane received no campaign medals because they were deemed to be POWS, although he did his duty as a soldier and escaped in February 1942 – even if he did not succeed. After a long battle for compensation in 2000, the British government announced an ex-gratia payment of £10,000 to surviving members of British groups held prisoner by Japan during WWII.

As a tourist when I attended the marriage of my son to his lovely Japanese fiancée, I found it imperative to learn what the Japanese knew of their war. In the entrance of the Great East Asian War Museum is saw a restored engine from the Death Railway in pride of place – its narrative was different from mine. I learned at Wampong Viaduct on the Death Railway about each sleeper: it was said: “One of wood as same as one [dead] man”.[3]

The “unlucky” ones carried on to Singapore: “Now came the realisation that the 5th Battalion of The Suffolk Regiment, part of a Brigade considered to be a most efficient and well-trained fighting force, had travelled 20,000 miles simply to surrender”after our “Greatest Defeat” on 15 February 1942. There is still controversy whether General Percival needed to surrender. [He was held in Changi prison with the junior POWS but other officers above the rank of Colonel were transferred to Manchuria until, on 2 September 1945, Percival closely witnessed the surrender of the Japanese and returned to the UK with the pension of his substantive rank of Major-General. He subsequently led the Far East Prisoners of War Association trying to improve their compensation. He died in 1966 aged 78.[3]

After a long delay in December 1942, the Japanese decided they needed to build a railway through mountainous jungle in Thailand and Burma to transport troops and materials rapidly by rail to assist their aim in capturing India. It was “promised” that those who “volunteered” would experience much better living and working conditions further north. That was a callous deception. The final death toll for the 3,334 British prisoners was 61.3%. Some like Messrs Key and Hemming were sent to work on the northern end and died of beriberi and cholera respectively – [Tewkesbury had lost over 200 to cholera in 1832 and 1849]. Both deaths were caused by deliberate neglect. They were buried in Buma at THANBYUZAYAT WAR CEMETERY, but relatives were not allowed to visit until 1996. Pte. Ryland was buried in the southern end at Kanchanaburi in Thailand,which was open to tourists from 1956, and such as I visited in 2004. Altogether it is estimated that approximately 12,500 out of 50,000 British soldiers died in Japanese POW camps, representing a mortality rate of 24.8%. They were treated so badly as the Japanese soldiers were indoctrinated, by their "Code of Battlefield Conduct”, that it was shameful to surrender.

Comments