Tewkesbury’s Own D-Day Hero

15 years ago to commemorate D-Day60, John Dixon escorted a group of veterans to the ceremony, presided over by the Queen. It led to research to ascertain if ay local men took part in the epic campaign. As far as we know, the only representative was Edwin J. Davis of church Street and Twyning. We learned that his widow was mis-informed that he had been killed on 8 June whereas the date was 30 June which indicates how long - and how brutal - was the campaign to break out from the Normandy beaches. It also sheds light on the historical controversy about Montgomery's leadership. As we start to commemorate D-Day75, was it really 15 years ago - and did any more local men lose their lives there? —John Dixon, June 2019

Cemetery: St Manvieu, Cheux, (John Dixon)

I have been very fortunate in 2004 to have had my historical antennae sharpened by two visits to Normandy. This research was inspired by a desire to commemorate the 60th Anniversary of D-Day by focusing upon a local man who lost his life in that campaign.

The first visit in February 2004 was pure pleasure, as I joined a visit with the Tewkesbury School P.T.F.A.. However, pleasure is all the more acute if History is involved; so prior to the visit I perused the pages of the Tewkesbury Register to see if any local men had lost their lives in the Normandy Campaign. The one I discovered was Edwin J. Davis, born in Twyning but living in Chance Street. As the research developed, I became deeply grateful for the help of Edwin’s brother-in-law, Reg. Eastman. However, I would like to share with you the fruits of this research as a tribute to this former Grammar School boy who lost his life, helping to liberate Europe. It also brings into focus that, beyond D-Day itself, it took two months of bitter fighting to capture Normandy.

Following on from the holiday visit, I had the honour of being invited by Galina Travel to act as Courier for one of their coaches visiting Normandy for the D-Day 60 celebrations. I was not able to follow up my research on Edwin Davis, yet it was a great privilege to help some wonderful veterans visit the scenes of so much suffering and to take part in the deeply moving Commemoration Service at Bayeux. In particular, we received a booking at very short notice from the daughter and granddaughter of our only V.C. awarded on D-Day – C.S.M. Stan Hollis.

The research took several stages and, by November 2004, it is finished - as far as it is possible. I have written this article as a research report following each stage chronologically, thus revealing the ‘blind alley’ in which I found myself in order to arrive at the definitive story. Edwin John Davis is now commemorated in Twyning Church and in the Town Hall, on the brass plaque testimony to those former pupils of Tewkesbury Grammar School who were killed in the war.

Research Stage 1: The Background

Having a planned visit to Normandy with the Tewkesbury School P.T.F.A. last February, we wished to discover if any Tewkesbury man had given his life as part of the Normandy campaign. This is not as easy as it would have been in the Great War, as local men were not allocated to the County Regiment. Thus, eventually, a trawl in the Echo’s predecessor, the Tewkesbury Register, revealed a “Twyning Soldier .. killed in action”.[1]

This was L/Cpl. Edwin J. Davis of 25 Chance Street: it was the receipt of news of his death by his wife that suggested an intriguing aspect: Mrs. Davis expressed the hope “to hear in the future the name of the ruined church in the churchyard of which her husband was laid to rest”. That was a challenge which we hoped to face with the help of our courier with Galina Travel.

The first source of information is the website of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission[2] and this revealed that our local man, son of Mr. and Mrs. Albert Henry and Francis Mary Davis of Hill End Twyning, was in fact serving with the 4th Battalion of the King’s Shropshire Light Infantry. It confirmed that he was 28 and that he died on 1 July 1944.

Stage 2: Visit in February 2004 & C.W.G.C. Military Cemetery: St Manvieu, Cheux

Galina, being a tour company dedicated to history, kindly agreed to a small detour and, with the help of fellow colleague Chris Poole, we soon found the actual grave. However, it was clear that this was a military cemetery and not the churchyard of Mrs. Davis’s recall.

A study of a local map, however, revealed that the church yard was, in fact, located next door to the cemetery, but that it was now ruined; possibly in the action which took her husband’s life. By this time I had an increasingly worried feeling that something was amiss!

Stage 3: The ‘Blind Alley’, investigating the 2nd Battalion K.S.L.I.

Tewkesbury Abbey on 4 December 1939.

(Eastman)Click Image

to Expand

There was a slight problem since Reg. Eastman, the brother-in-law of Mrs. Davis, had told me that she had been informed by the War Office that her husband had been killed on 8 June 1944.[3] I paid too much heed to this information and this led me to the erroneous assumption that Edwin had, in fact, belonged to the 2nd. Battalion of the K.S.L.I..

It did not help that Max Hastings featured this battalion quite prominently in 'Overlord'. According to him, “it is no exaggeration to say that the sole determined thrust …. Against Caen that day was the K.S.L.I., supported by other units.” [4]

The [2nd Battalion] King’s Shropshire Light Infantry landed on Sword Beach near Hermanville: they were cheered by locals and took many voluntary prisoners by 9 a.m.,[5] but their tank support was held up on the beach by a traffic jam. The battalion commanding officer used a bicycle to ride to and from the beach to establish the position after which they were ordered to march on Caen without support. They fought a brisk battle over Hill 61 and then reached Biéville in the afternoon but, just three miles from Caen, at Lebisey Wood, they encountered determined opposition from the 21st Panzer Division. And “here, late on the evening of 6th June, all hope of reaching Caen vanished”. Of the Battalion, Hastings concludes that “their achievement had been remarkable”. It was to be after five weeks of bitter fighting that Caen fell to the Allies on 10 July.[6]

The activities of the 2K.S.L.I. are not clear thereafter in the books, but Davis was [I then believed} killed on the second day (8 June 1944) of an unsuccessful direct attack on Caen – but St. Manvieu, Cheux is several miles west of Caen, while the battalion had paused north of Caen. The trail was going cold.

However, my way out of this seemingly lucrative ‘blind alley’ was provided by a source from South Africa!

Stage 4: ‘Back on track’ - thanks to the family

The return to England, however, did not end the historical quest; a Twyning resident amongst our party made contact with a local man, Jim Healey, who gave me the address of Mrs. Davis – to whom I duly wrote hoping to show her photographs of the churchyard.

However, she had moved to Zululand in South Africa, and so my hopes were not high. Sadly my letter was a little time too late since Mrs. Davis had died recently – but I did receive a phone call from her brother-in-law Reg. Eastman. He had married Edith Davis’s sister, Freda, and both hailed from Tewkesbury. Apparently Mrs. Davis had emigrated to South Africa in 1949 as a lady’s companion. There she met and married an Englishman, Alfred Dowe by whom she had a son, Jimmy. It is Jimmy who has so kindly sent me papers belonging to his late mother.

These papers, however, indicated that St. Manvieu, Cheux was, in fact, the second place of burial: the first is a much more poignant story which has been culled from an unknown newspaper.

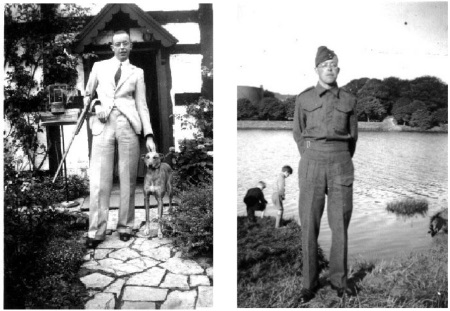

At the same time, Peg Eastman told me that “Edwin worked as a barman in the Quinton area of Birmingham and I gather that he was a quiet and friendly individual”. Jimmy enabled me to learn more about the person behind the uniform by supplying me with photographs:

However, I realised that it was inevitable that I would have to visit Shrewsbury!

Stage 5: Site visit to K.S.L.I. Museum,Shrewsbury on 3 September 2004

Another reason for my disquiet came just before the 60th Anniversary, when I telephoned, Mr. Duckers, the curator of the K.S.L.I. Museum at Shrewsbury: he kindly was able to shed some contradictory light.

He confirmed, from their records, that Edwin in fact had served in 4K.S.L.I. and had landed on D-Day+ 8 (14 June). The battalion was involved in heavy shelling west of Caen and it is likely that this was how Edwin died during the night 30 June/1 July 1944. This accorded with the CWGC records – but I still did not know why his widow was informed that 8 June was the date of death. The exact location of the death was also still not clear.

4K.S.L.I.: Part I: Before France

The Battalion was part of the Territorial Army[7] but it saw no fighting until the landing in Normandy on D-Day + 8. It was, therefore, an unashamed local battalion although, in May 1940, it absorbed an intake of 350 raw recruits who were not ‘Salopians’. Most arrived from the Potteries in Staffordshire – but did the intake include our Tewkesburian, Edwin Davis?[8] Major Thornburn, the most recent battalion historian, concedes that this contingent was considered to be the backbone of the Battalion, as it slogged through Normandy to Antwerp and beyond.[9] Its most valuable period of training took place in Yorkshire where the Wold terrain was similar to that of Normandy. However, they were very disappointed that they were not needed in the North African campaign. There was some compensation, because the battalion was involved in training with the experimental 11th Armoured Division, commanded by Major-General Percy Hobart, who went on to find fame because of his ‘funnies’ during D-Day – flail tanks and other engineering inventions which helped make the landing successful.[10] He was also experimenting in combining armoured and infantry brigades within the armoured division – but this skill was apparently learned the hard way during the battle in which Edwin Davis was killed.[11]

D-Day on 6 June 1944 found them still at Aldershot: it was not until 13 June that they embarked for France at Newhaven.

4K.S.L.I.: Part II: ‘D-Day + 8’

to Expand

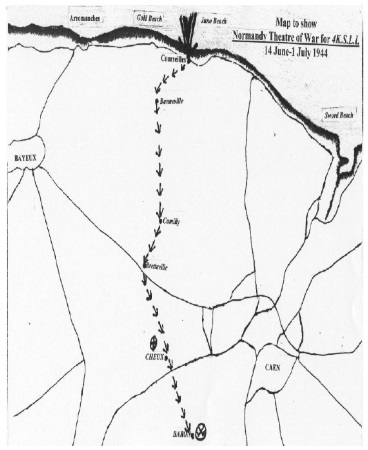

On 14th June they landed at Corseuilles sur Mer (Juno Beach) with no casualties, despite the shelling, with the battalion spending first night at Bannville before gathering at Cainet. Here there was little local welcome for these ‘liberators’. It is also significant that it was only on 21 June that they sighted their first two enemy aircraft.

The nemesis of the battalion was to be ‘Operation Epsom’ whose aim was explained, at a briefing on 25 June, that it would attack Caen from the West. Historians have debated whether this operation was a failure or a success; and, if the former, how far Montgomery was to blame. On the 27 June, the battalion left via Norroy-en-Bessin, Camilly, Bretteville and Cheux, where there was much evidence of heavy fighting, until they crossed the River Odon without excessive losses. They were, however, subject to mortar shells and lost their first casualty; in addition they experienced ‘Moaning Minnie’, a shell whose “bark was worse than its bite”, it was subsequently realised.

I contacted a survivor of that campaign, Sgt. Harry Langford, who thought that Edwin may have served with B Coy, which along with the HQ was located in the grounds of Chateau de Baron. Unfortunately for them this was in firing range of their “Calvary”, Hill 112 with its gentle slope, from which they were “shelled all the time”. Their own mortar range-firing “thickened up [the German] mortar and artillery fire”.[12] Both Shropshire authors allege that the accurate fire was directed by a Frenchman with a radio.[13]

There was three days of fighting when the battalion took nine deaths. A more serious counterattack ensued, however, at dawn on 1st July – when three enemy battalions infiltrated their lines. ‘C’ Company on the right was worst hit, although it was, to some extent, protected by defensive artillery fire. Eventually the attack was repelled. Later, the mortar platoon, posted behind Baron Church, came under heavy fire and C.S.M. Baker won the Military Medal during that “terrible night” of action; this was deemed, in hindsight, “a fine tonic”.[16] The severity of the battle was measured by Major Ellis who claimed that “they started to stonk us in no uncertain terms”. Sgt. Langford thought Ellis was Edwin’s commanding officer. On the same night, Kemp noted that “severe and accurate shelling on the night of 30th June heralded a heavy enemy attack during the early morning…..; though the artillery fire also caused some casualties when it enveloped ‘C’ Company’s forward posts and the carrier and mortar positions…casualties were inevitable”.[17] Despite this, the military historians concluded that “The success of the action gave great encouragement to the Battalion”.[18] The attackers had been none other than the 9th/10th Panzer Divisions of the SS, the size of which was measured by the 23 captured machine guns, 25 infiltrators killed and the 10 prisoners taken. Thornburn implies that the 10th were even more formidable after taking twelve days to arrive by rail from a successful battle in Russia.[19] Thornburn made the best of it by declaring that the “night turned soldiers into warriors, and trained troops into hardened men-at arms”.[20]

Unfortunately, the battle also turned Edwin into a fatal casualty. I am still not sure how he died but a clue may lie in that ‘poignant story’, contained in his widow’s papers. Kemp reported that the H.Q. mortar platoon, sited in a field behind Baron Church, came under “very heavy small arms fire.” Perhaps Edwin’s life was extinguished by that sniper, the like of whom, Thornburn pointed out, became “a complete phobia of the Allied troops”.[21]

Also lost in this engagement was the C/O, Lt. Col. H. P. ‘Mossy Miles’ who suffered a nervous breakdown, Thornburn suggesting that such a 45 year old reserve Officer should have been relieved before they landed in Normandy.

Was this death of Edwin in a good cause? Thornburn blames the “confusion” and “off the cuff” direction that characterised the whole of the Epsom battle. He is particularly critical that the Infantry Brigade tended to be used as “a convenient ‘spare part’”. [22]

Stage 6: A Disappointing Post-Script

The story was still not complete, since there was one more source to research: the service record of Edwin Davis. In theory, it is open to the next of kin from the Infantry Records Office. I had to write to this establishment twice and wait an inordinately long time before I was honoured by a reply. When it came the bad news would be the fee of £25 (free if for next of kin) - and the really bad news was that a wait of six/eight months is involved!

Thus ended, in a bureaucratic anti-climax, a fascinating research journey. I hope, therefore, that I have given posthumous life to a young man who sacrificed his life in the long and bitter aftermath of D-Day, sixty years ago.

4K.S.L.I.: Part IV: Aftermath

Unfortunately for our research, Max Hastings in ‘Overlord’ did not interview any members of this battalion. However, he does concede that the battles described here “was a fine fighting achievement by the British divisions”. He also criticises the Army Commander Dempsey for withdrawing from the attack and relinquishing Hill 112 in an attempt to conserve lives. Concerning Montgomery, he concedes that morale amongst the troops was buoyed up by his claims that all was “going to plan”; it was not worth the loss of men to hold on to ground as had happened in the Great War. Hastings castigates him for believing in his own propaganda. Nevertheless – and perhaps a little inconsistently – he concludes that the failure to take Caen revealed a “weakness in the fighting power and tactics within the British army rather much more than a failure of generalship by General Sir Bernard Montgomery”. [23]

Thornburn cannot bring himself to be too critical of Montgomery. [24] “The Germans withdrew their force – what was left of it – up the hill shortly before dawn”…. [it was] a watershed [which] marked the end of Epsom Operation properly”. Epsom “was the beginning of Montgomery’s battle for position which would lead to the final American break-out in the west …”. The Germans lost so heavily that now they were forced onto the defensive: it was “a soldier’s battle in which the Generals failed to organise an orderly and well planned operation”. It was here that he criticised the tactics that treated infantry and armoured brigades separately.[25]

Relief came on 4th July. By 16th, with a new C/O, they assembled at Benouville for “Operation Goodwood”, another campaign aimed at taking Caen; it was not an outstanding success.

Thornburn disagrees with Kemp’s assessment that casualties were “on the high side” but he does admit that 114 casualties constituted 10% of the battalion and that, lost so early in the campaign, they were fully trained and thus irreplaceable. At Baron today, there is a memorial in the field which was so heavily mortared. I must find the opportunity to visit that spot and the church which Edith, Edwin’s widow, expressed a desire to see.

References

- Tewkesbury Register 22 July 1944.

- www.cwgc.org.uk

- Telephone conversation with brother in law Reg.Eastman who recalled that she had only received this official notification on 25 August 1945.

- Max Hastings, Overlord, (London, 1984) pp 134-7,138.

- David Evans, a Guide to the beaches and Battlefields of Normandy, (London, 1994), p119. David Evans was reared partly at 49 High Street, Tewkesbury before undertaking an academic career.

- Evans p32.

- Mr. Duckers informed me that he 4K.S.L.I. was ‘formed’ in 1908, from the men of the existing Shropshire Rifle Volunteers. Most of its men in 1939, when it was embodied for war service, were old hands with many years of training under their belts. The battalion did, of course, have a very distinguished background; in WW1, it was one of very few British units to be awarded a unit Croix-de-Guerre by the French (for Bligny Hill, June 1918).

- Edwin’s service record would have confirmed this but, as explained later; it was not practicable to obtain it.

- Major ‘Ned’ Thornburn, MC, TD, MA, The 4th K.S.L.I. in Normandy (Castle Museum, Shrewsbury) p1.

- Lt. Commander P. K. Kemp FRHistS., R. N., The History of the 4th Battalion K.S.L.I. (TA), 1745-1945 (Shrewsbury, 1955) p66.

- Thornburn p p58.

- Thornburn, pp 31-32, 35.

- Kemp p79.

- Thornburn, pp 42.

- -

- Kemp P85.

- Thornburn p43 & Kemp p82.

- Kemp p255.

- Thornburn p42.

- Thornburn p48.

- Thornburn p34.

- Thornburn pp35, 40.

- M. Hastings, Overlord, (Pan Books, 1984) pp166-180.

- Thornburn p50.

- Thornburn p58.

Comments