The Unfought Battle of Tewkesbury

The Background

In 1939 and 1940, Britain and France had assumed that the forthcoming battles with German forces in continental Europe would be largely a repeat of World War I: their defence plans, as well as their tactics and their equipment, largely reflected that. The British sent an Expeditionary Force [BEF] to fight alongside the French, as they had 25 years before – but with both armies having apparently forgotten some of the lessons of the Great War. Since then, the Germans had developed their all-arms ‘Blitzkrieg’ techniques which included the use of paratroops or glider-borne troops to capture key points behind the opposition’s front line.

The simultaneous attacks on Holland, Belgium and France had come in the early hours of 10 May 1940. On 14 May, Anthony Eden, the newly appointed Secretary of State for War in the Churchill government (itself only formed on 10 May), announced on the radio that men were wanted throughout the country to form the Local Defence Volunteers [LDV], whose initial role would be: to keep watch for enemy parachutists, report their presence to the regular forces, disable them as best they could and man the fixed defences in their locality. Their role would rapidly expand to include guiding regular counter-attack forces through their area of responsibility; help the police man traffic control points on all roads entering towns and villages, particularly at night, to check for enemy agents and saboteurs; place a guard on so-called vulnerable points to prevent acts of sabotage or destruction; and immobilise petrol stocks and any vehicles that might be utilised by the Germans. With the promise of weapons and uniforms, the response to this call, by men not already in military service, was immediate and widespread. The force, which nationally was to reach almost two million men, and some women at its peak, was quickly renamed the Home Guard at the behest of Winston Churchill. A large proportion of these volunteers had served previously, many in the Great War, and had experienced fighting the Germans: they did not require any urging to take on the old foe!

- Airborne landings on the Berkshire and Newbury Downs,

- Airborne landings elsewhere directed against aerodromes and vital centres,

- Seaborne landings in the Bristol area[2]

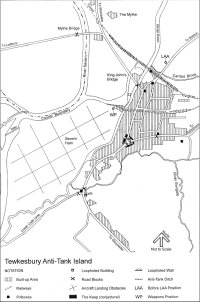

In the Central Midlands Area, the threats were envisaged as an AFV attack which may have broken through the beach defences to a considerable depth and found its way inland, and a large scale airborne attack.[3] In order to protect the West Midlands, a series of ‘stop-lines’ based on existing river and canal systems, together with a number of urban areas designated as ‘anti-tank islands’, were planned to surround this key aircraft and armaments-producing area.[4] Tewkesbury occupied an important position in the defences around the West Midlands, linking two major stop lines formed by the rivers Severn and Avon. The town was designated as an anti-tank island (under the command of the RASC Depot at Ashchurch) but, sadly, no detailed defence plans for the town have so far been discovered.[5]

The underlying principle of these defence measures was to confine the movement of enemy AFVs and to hamper them further at focal points of communications (essentially major road junctions within anti-tank islands). Anti-tank island defences were to be a ring of anti-tank obstacles around the area, consisting of buildings and natural obstacles, supplemented with road blocks, rail blocks and short lengths of anti-tank ditches or anti-tank scaffolding. Anti-tank minefields were to be laid on ‘action-stations’ and defended localities were to be prepared to cover the anti-tank obstacles.[6] Potential landing grounds for enemy troop carrying aircraft were to be obstructed by various means including trenching, as on the Tewkesbury Ham, or by poles or old cars set out in a pattern across the open space. All these methods were used in the Midlands, following the issue of instructions to local authorities, which were to carry out the work required. A number of mobile counter-attack columns have been identified for Worcestershire which no doubt would have come to the aid of Tewkesbury, including one at Norton Barracks and, from Malvern, three organised by an infantry brigade and another by the Royal Navy (HMS Duke). The infantry training centre in Gloucester also formed a column and no doubt there were others in Gloucestershire. All anti-aircraft gun batteries, searchlight sites and barrage balloon sites were to create a defence perimeter around their individual sites and take on any enemy troops in their vicinity. Both a ‘Bofors’ light anti-aircraft gun [LAA] and a searchlight were located on the road to Bredon, and more Bofors were located around the Ashchurch Depot, while a searchlight battery headquarters occupied The Mythe.

Instructions for the employment of the Home Guard explained that the primary duty was to obstruct the enemy, harass him, destroying him wherever possible. The Home Guard were to achieve this by holding defensively their own towns and villages. All defensive localities were to be held to the last man and last round. Road blocks were to be capable of being placed in position or removed in ten minutes (to allow counter-attack forces through). The road on the far side (presumably meaning the enemy side) of the block was to be covered by defensive positions. These positions were to be manned on action-stations. It was recommended that the best defensive work was a well concealed infantry trench. Few trenches can now be identified, having been back-filled at the end of the war, but they were dug in their hundreds by the Home Guard throughout the Midlands.Tewkesbury's Home Guard

to Expand

Tewkesbury’s Home Guard was part of the 1st Gloucestershire Battalion which had responsibility for defence of Cheltenham (itself initially designated as an anti-tank island) as well as the rural area to the north as far as Twyning, and stretching from Forthampton and Apperley in the west to Toddington and Winchcombe in the east. The whole of the rural area was the responsibility of A-Company but, by the end of 1940, it was clear that the area covered was too great. The Tewkesbury District force was therefore separated to become E-Company, numbering about 250 men, and was commanded by Captain Philipson-Stow, with Lieutenant Comins as second-in-command. Platoon officers were: Lieutenant A.E. Berry for Tewkesbury, including Forthampton and Chaceley; Lieutenant S. Bass for Coombe Hill; and Lieutenant B. Fletcher for Twyning. The Mill and the Forthampton Sections of the Tewkesbury Platoon were later separated to form another platoon under the command of Lieutenant John W. Healing.

Apparently, under the guidance of Lieutenant Burgess, E-Company became pioneers of flame throwing, demonstrations being given in Tewkesbury and at Aggs Hill, Cheltenham. The Company was fortunate in having good NCOs, veterans of the Great War, and, with assistance of instructors from Cheltenham, it soon gave a good account of itself in tests for preparedness and efficiency. Bombing practice was carried out on the Ham, while shooting was conducted at Bushley and Forthampton, achieving a respectable degree of efficiency. The arrival of rifles and automatic weapons from America in July 1940 meant that the initial shortage of Home Guard weapons was quickly corrected.

The Defences of Tewkesbury

What of the defences, remembered by Brian Linnell? These are shown in the diagram along with others gleaned from aerial photographs and interviews with local people. The location of most of the pillboxes is corroborated by a map showing the location and notes dealing with the demolition of them held by the Gloucestershire Archives.[8] It has become fashionable to denigrate the efforts of the British Home Defence planners of 1940 and, indeed, the Home Guard, partly encouraged by the impression given by the Dad’s Army TV comedy. Sadly, Brian fell into that trap! The reality was different and although the sites shown on Figure 1 were the most obvious defence features, there will have been a significant number of less obvious defences in and around Tewkesbury. As an example, some of the ‘gaps’ identified by Brian would almost certainly have been used to locate anti-tank mines. These would have been stored in the town ready for use in the event of an attack developing in the vicinity. Nevertheless, from what we know, a clear pattern of defence can be discerned, and this follows closely the approach taken in other anti-tank island defences (where original defence plans have survived).

Responsibility for planning and organising the defences in the South Midlands Area was given to V-Corps, then based in Oxfordshire. Reconnaissance parties would survey the defence areas and mark out with pegs and paint the position of proposed defence works. They would then be followed by Royal Engineer Field Companies, which would requisition land and buildings needed for defence, and direct Pioneer Corps men, local authority labour and civil engineering companies in the construction of the defences.[9]

At Tewkesbury, the key objective for capture by the enemy would have been the river crossing provided by King John’s Bridge, in order to allow an armoured column to move north towards Birmingham. Speed was crucial and so parachute troops would have been used, probably dressed in British uniforms in an attempt to confuse the defenders. These would have been dropped close to the bridge, probably on the Ham, followed by air-landed troops. The grid-pattern of trenches was dug there to deter troop-carrying aircraft from landing but, if they did land, to damage them so severely that they would be of little further use to the enemy. The emplacement at the north end of the Ham, remembered by Brian, was perfectly placed to sweep the Ham with machine gun fire, but it is likely that the two mills would have provided more fire positions. The approach of any enemy armoured column to Tewkesbury would have been seen and reported by the Observer Corps posts on Alderton Hill, Bredon Hill, Cleeve Hill,[10] or closer to the town by the various air defence troops in the vicinity. The Home Guard, too, would have had their outposts and observation posts to report on any enemy movements. Brian identifies one such post on the small hill to the south of the town, but others were likely on The Mythe Hill, on the roof of Healing’s Mill and on the Abbey Tower.

It is self-evident that the Severn, Avon, Mill Avon and Swilgate Rivers, the railway embankment to the north, and the closely packed buildings of the town, are more than adequate obstacles for armoured vehicles, obviating the need for barbed wire. Tanks and other military vehicles and urban areas do not mix, as was proved many times over during the war. Any vehicle is vulnerable to overhead attack with phosphorus grenades from the buildings overlooking them. The enemy column would therefore seek to pass through the town as quickly as possible using the roads, or go the long way around, thereby incurring delay, and probably meeting other defended areas to add to the delay.

Road blocks were therefore placed on all the main approaches to the town centre to delay the column. Should any of these blocks fail, then the blocks around the War Memorial would be where the critical battle for Tewkesbury’s roads would be fought. Known as ‘The Keep’, every anti-tank island had one located around the key road junction which, in those days before bypasses and motorways, was usually in the centre of town. Here, the surrounding buildings would have been prepared for defence by sandbagging windows and ‘loop-holing’ walls to provide fire positions overlooking the junction. It was also here that the garrison commander would locate his reserves, ready to counter-attack should any of the outer defences show signs of failing.

to Expand

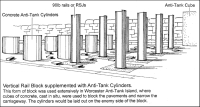

The ‘asparagus blocks’ mentioned by Brian are in fact known as ‘vertical rail blocks’ (see Figure 2) which, together with concrete cylinders, formed a more than adequate anti-tank block for the generally light tanks employed by the Germans early in the war. This type of block could be erected quickly, or dismantled to allow counter-attack forces through. The defence arrangements described by Brian around the Swilgate Bridge, to the south of the town, are the perfect tank trap: the brushwood filled ditch awaited any tank commander, seeking to avoid the block on the bridge by diverting into what is now the playing field! The fire positions in the vicinity would have deterred any enemy troops from climbing out of their tanks, or trying to dismantle the block. The anti-tank gun emplacements have been recorded on all the main river crossings on the Severn and Avon, and one still exists at Holt Fleet Bridge, west of Ombersley, Worcestershire. There must have been one at Tewkesbury, but where? It would be most likely to have been sited on the town side of the Avon, covering the critical block on King John’s Bridge, as well as the railway bridge over the river, to the north. Can anybody remember it? Perhaps the ‘pillbox’ at the north end of the High Street was the emplacement? The anti-aircraft Bofors gun on the Bredon Road, as indeed those around the Ashchurch Depot, would have been used in an anti-tank role, once enemy armour came within its range. The defences around this gun would have included a road block, probably under the railway bridge. Does anyone remember this?

Tewkesbury’s defences were not isolated, but part of a web of static defences throughout the Midlands, designed to enmesh enemy armoured columns and to prevent the rapid progress that such columns had enjoyed in France. Each defence area would impose delay on the enemy, even if the defenders were eventually overcome. Time would, therefore, have been bought to enable the mobile columns of the regular home defence forces to move into position for a counter-attack. Thankfully these arrangements were not tested in battle, although a number of Home Guard exercises with other units included a mock attack on the town.

The successful D-Day landings in France in June 1944, and the large numbers of American troops then in Britain, brought to an end the likelihood of a full-scale attack on the country by German forces (although spoiling and sabotage attacks on stores and communications by German parachutists were still considered to be possible). The steel used in the road blocks was quickly collected to make up for the shortage of metals in 1944. Pillboxes started to be demolished soon after the war was over. The American forces at Ashchurch apparently undertook some of this work in Tewkesbury. The Home Guard stood down in December 1944 and disbanded in December the following year. All that remains of Tewkesbury’s 1940s defences are the trenches which can still be seen on the Ham (despite what Brian said) and the blocked ‘loophole’ in the house to the south of the Swilgate Bridge. A concrete cylinder or two can just be glimpsed on the side of the road to the north of the town at Shuthonger. Further afield there are some remnants of the Avon Stop Line, notably at Eckington and Pershore bridges. As a result of his researches, the Author is in fact very impressed by the range of defences constructed and by the quality of thinking which was invested in the defence of Britain.

References

- National Archives [NA] CAB 120/237, Cabinet Papers. See also, Basil Collier, The Defence of the United Kingdom (HMSO 1957).

- NA, WO 166/1224, South Midlands Area War Diary for 1939 to 1941.

- NA, WO 199/1800, Southern Command papers dated June 1940.

- NA, WO 166/94, Western Command War Diary July 1940.

- The South Midlands Area Operational Instruction No. 5 of October 1940, Royal Army Service Corps.

- NA, WO 199/544, Southern Command file on Anti-Tank Islands, etc.

- See Gloucestershire Archives [GA] MI1 for a short history of the 1st Gloucestershire Battalion Home Guard.

- GA, D 5274.

- NA, WO 166/3686, The War Diary for the 217th Field Company RE (of 3 Corps, then based in Shropshire) lists the works carried out along the River Avon during 1940, and is one of the few Royal Engineer reports to have survived. It illustrates the sort of works that would have been carried out by 5 Corps Engineers in the Tewkesbury area.

- From Derek Wood, Attack Warning Red – The Royal Observer Corps and the Defence of Britain 1925 to 1992, (Carmichael and Sweet, Portsmouth, 1992).

Comments

Tuesday 13-Aug-2024 by: Michael Condon

was there a flood in 1943-44?

Wednesday 10-Mar-2021 by: Dianne Sharp

When my father left my mother we were evicted from the tied cottage in Corse Lawn and found a home in a Nissan hut on the former army? Camp at the Mythe. I was about 6 at the time but remember living there for some time before being rehoused in Tewkesbury.There was a grand house at the centre which had been turned into flats and we knew a family there.My mother actually found work at a big house down the hill , was it a Mr Musgrave Morris ?We sometimes went with her and had to be very quiet It was such a close community and I would love to know more of its history. I wonder what is there now

THS writes back:

Dianne: If you email me I can send you more information - your maiden name would be useful as one of my colleagues, Marion, was a child there with an excellent memory. - John Dixon