The Elections of John Martin

In the Eatanswill election Mr. Fizkin is pitted against Samuel Slumkey, whose agent, Perker, explains contemporary election methods. “Fizkin’s people have got three-and-thirty voters in the lock-up coach-house at the White Hart ... The effect, you see, is to prevent our getting at them. Even if we could, it would be of no use, for they keep them very drunk on purpose.”

Charles Dickens, The Pickwick Papers, published 1836-37

Street by John Biddulph Martin,

pub.1892 (Michigan Univ.)

At nine in the morning of Tuesday 11 December 1832, aspirants for election as MPs for the two seats of the Borough of Tewkesbury assembled at the ‘hustings’ platform erected in front of the Town Hall in the High Street. The three candidates were Charles Hanbury Tracy (Whig), William Dowdeswell (Tory) and the twenty-seven-year-old John Martin (Whig). Each candidate was formally proposed and seconded, Martin by Messrs. Winterbotham and Hartland.

After speeches from the three, the polling began at eleven. At four o’clock the first day of voting closed; Tracy had 195 votes, Martin 188 and Dowdeswell 168. Polling resumed the next day at eight; then, early in the afternoon, Dowdeswell retired from the contest as he saw that he could not win. The final count was Tracy 210, Martin 195, Dowdeswell 184; the two Whig candidates were therefore returned. Afterwards the newly-elected members were drawn through the main streets of the town in an open carriage decorated with their colours. Three weeks later John Martin hosted a sumptuous dinner at the Cross Keys Inn for 160 of the electors that had supported him.[1]Before the ‘Great Reform Act’ of 1832[2] few people had the vote, mainly substantial property-holders. The electorate for the Borough of Tewkesbury in 1831 numbered around 523,[3] although at least half of them were not even resident in the borough.

In 1831 the proposed Reform Bill was fiercely opposed by the Tories. Tewkesbury’s Tory MP, John Dowdeswell(William Dowdeswell’s father)4 voted against it which triggered violent demonstrations in the town. When the House of Commons managed to pass the bill the House of Lords repeatedly blocked it.

Eventually, threats to create enough Whig Peers to enable its passage led to the bill becoming law in June 1832. Among other reforms the voting system was reorganised: every male over the age of twenty-one who had a lease on land worth more than £10 for at least sixty years, or worth more than £50 pounds for at least twenty years, or tenants paying an annual rent of £50 pounds, was given a vote. The number of days that voting was open was restricted from forty days to just two and multiple polling areas were established.

Nationwide, many elections went uncontested – a third in 1841. This was often because those aspiring to enter Parliament could not afford the high costs of standing, or of being a Member as MPs were not paid. Candidates shared the official costs involved in addition to their own expenses; they also of course funded the widespread practice of ‘treating’ electors and, in many seats, outright bribery. It is no coincidence that all who stood for election in Tewkesbury during this epoch were, by modern standards, multi-millionaires.

A letter from a member of Charles Tracy’s Election Committee of 1831 gives us some idea of the costs of standing. He details sums subscribed to defray some of Tracy’s expenses. The total amounted to over £1,088 [around £60,000 in today’s values]. He added “our descendants will doubtless wonder at the folly of their ancestors in subjecting their representatives to such wasteful and mischievous charges as some of these items exhibit”. One item was £262.19s.6d. for “sundry bills for ribbons”, another £46.17s.7d. for “two bands of music and ringers” and over £235 for “innkeepers’ bills”. Bennett noted, “The expenses of each of the successful candidates must have far exceeded those of Mr. Tracy’s committee.”[7]

Elections could be decided by a show of hands at the hustings regardless of whether the hands belonged to the enfranchised or not. Only when a candidate defeated by the show demanded it would a poll be held, with voting restricted to those who were enfranchised. During the Chartist agitation of the 1840s, the Chartists often attended the hustings in large numbers and raised their hands for their unofficial ‘candidate’ – usually winning the show but not going forward to the poll. A few Chartists did formally stand for election (although not in Tewkesbury) but made little headway.

to Expand

Casting votes in the poll was a public business. A voter stood on a platform where his eligibility to vote could be challenged by any of the candidates. Some constituencies returned two members (Tewkesbury being such a case) and the voter had to announce his choice, or choices, in front of the audience and the candidates, who often included his landlord or employer. Those that chose to use only one of their votes were known as ‘Plumpers’.

John Martin was born in London on 2 February 1805, the son of John and Frances Martin. John Martin senior was an MP for Tewkesbury in six successive Parliaments and his father, ‘honest’ James Martin, also held the post for over thirty years. John Martin senior had died at the beginning of 1832 and the town paid him great respect when his funeral cortege rested in Tewkesbury on its way to Ledbury for his burial.[8]Although the Martins are considered to have been Whigs (Liberals), it should be remembered that, at the time, political parties were rolling coalitions of shifting interests and outside of Parliament did not exist in the formal structured sense as they do today.

The Martins generally supported reform and John Martin senior received the praise of the leading radical William Cobbett when he described Martin (along with a few other MPs) as men who “despise power in the pursuit of justice”. Nevertheless, some years later Cobbett, in a shockingly anti-Semitic newspaper article, criticised Martin senior for presenting a petition to Parliament in support of Jews.[9] (Such anti-Semitism was common in Radical circles at the time.)

On 20 February 1834, Martin presented a petition to the then Whig Prime Minister, Earl Grey, on behalf of the Baptist and Independent Congregations of Tewkesbury, complaining of discrimination against them in such laws as non-conformists having to marry in an Anglican church and having to pay church rates to support the Church of England. As the petition was presented, Martin suffered an apoplectic attack but soon recovered.[10]

During his first term of office, John Martin voted for several reform moves, although most failed to achieve majority support. Among them, he voted for a Select Committee to look into alternatives to the impressment of seamen (‘press-gangs’), for anti-corn-law measures, for an inquiry into the Pension List, the enabling of Jews to become MPs and for shorter Parliaments.

At the next general election the same three candidates contested Tewkesbury. Proceedings commenced at eight o’clock on Monday 5 January 1835. The electorate numbered 392 of whom 379 recorded votes. After the first day, Martin held a small lead in the poll. However, the final figures were, Tracy 195, Dowdeswell 195 and Martin 192.

Two weeks later one hundred and thirty-four electors and thirty-nine other men sat for a dinner at the Swan Hotel held in honour of Martin and Tracy. The defeated Martin was presented with a silver vase inscribed as follows.

The Inhabitants of Tewkesbury present this Vase to John Martin, Esquire, in acknowledgment of his faithful services as their Representative in the first Reform Parliament; and as an affectionate Memorial of the independence and integrity in his public conduct, which for more than half a century distinguished his Father and Grandfather as the Representatives of their Borough.—20th January, 1835.[11]

While relieved of parliamentary duties Martin no doubt devoted time to his banking interests. He was the senior partner in his family’s bank in Lombard Street, London, known by the sign of the ‘Grasshopper’. He also must have spent time courting, as he married Mary Morse at Glamorgan on 31 October 1837; she was the daughter of the late Captain T.A. Morse. Mrs. Martin gave birth to a daughter in 1840, christened Elinor.

In Tewkesbury it was rumoured that Charles Tracy would be raised to the peerage and would resign his Commons seat. He did so, but for health reasons. He became a lord in the following year, as Baron Sudeley of Toddington (he had built and lived in the gothic-style Toddington Manor – now the home of the artist Damien Hirst).

Upon the death of King William IV in 1837 it was clear that another general election would be called. In the evening of the actual day on which the king died, John Martin arrived in Tewkesbury from London with a letter from Tracy which announced Tracy’s resignation and his recommendation of Martin to the electorate.

The Tory candidates were William Dowdeswell again and initially Henry Spencer Law, a London barrister and brother of the local Lord Ellenborough of Southam House. However, Law withdrew and a late stand-in was Joseph Peel, a relative of the then Tory Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel.[12]

The election in Tewkesbury began on Monday 24 July 1837 with nominations. The candidates were accompanied by their partisans carrying banners and flags. One banner in Martin’s colours proclaimed “Victoria, our patriotic Queen”. On entering the town, Martin’s men took the horses from his carriage and drew him to the hustings accompanied by a band. Dowdeswell arrived attended by a great number of his tenants, on horseback. Peel’s supporters carried a “costly and superb silk banner” inscribed with “Peel and the Constitutional Monarchy”, which was made by some ladies of Tewkesbury and was presented to the candidate.

However, the festive spirit soon dispelled. After nominations (Martin’s by Rev. W.L. Townsend and Mr. J. Petley, a Quaker) fighting broke out during the speeches: a table on the hustings was broken and the table legs used as weapons. The candidates fled to the Town Hall until peace was restored. Dowdeswell and Martin then won the show of hands and Peel insisted on a poll. Voting took place the next day; Peel lost again: the final figures were, Dowdeswell 199, Martin 192 and Peel 169.[13]

It was the tradition to ‘chair’ victorious candidates through the streets of Tewkesbury. Dowdeswell’s chairing took place two days after the election, Martin’s not until Friday, 4 August. Martin was paraded through the streets amidst banners and flags, preceded by a band. He was enthroned in an ornate chair, with a large bronzed figure of a lion in front. Above was a canopy, with a representation of ‘Fame’ on the top. Behind was a winged figure, holding a wreath over his head. The chair was on a raised, wheeled-platform, hauled by about thirty voters wearing hats and scarves in Martin’s scarlet and green colours.

The proceedings went well until the contraption entered the gates of the Town Hall. The platform became separated from its wheels and Martin was thrown backwards with considerable force. He was caught in mid-air by one of his supporters preventing a heavy fall onto the ground. Mustering his dignity, John Martin and about a hundred and fifty of his supporters retired to the Cross Keys Inn to dine.[14]

A year after the election, eight of Martin’s supporters were prosecuted for having voted without being enfranchised. They were: William Baylis (maltster), James Crump (stocking-maker), Richard Wilmer Hawk (hosier), George Hawkins (labourer), Thomas Keys (glazier), John Price (brazier), Richard Price (barge-owner) and John Smith (school-master). Of course eight votes would not have affected the outcome of the election and the prosecutions did not proceed, although the eight had to pay court costs.[15]

During this Parliament the Chartist agitation was at its height. The first Chartist petition was presented to the House of Commons in May 1839. Much to the pleasure of Tewkesbury’s leading Chartist, William Morris Moore (and to the disgust of some of the Gloucester Press) Martin was one of only forty-six MPs to vote in support of it.[16]

The winter of 1840 brought harsh weather conditions and an economic depression caused increased distress among the poorer people of the town. Public subscriptions amounting to £359 were collected to subsidise the selling of coal at 4d. per cwt and 6d. loaves at 4d. John Martin contributed £30 as did William Dowdeswell.

The next election was in 1841, when Dowdeswell and Martin stood again; they were joined by a ‘Liberal’ (as the Whigs were increasingly known), John Easthope junior. The final result was Dowdeswell 193, Martin 189, Easthope 181.

Martin broke with tradition in not being chaired after this election. Instead he funded the provision of meat for the poor and beer for everyone aged over sixteen, as well as holding the usual great feast at the Cross Keys Inn. The Liberal-leaning Gloucester Journal[17] reported these events.

This town yesterday was the scene of unexampled gaiety … Seven prime beeves, as many sheep, and a number of lambs, were distributed to every poor inhabitant of the place without distinction of party … The hon. member perambulated the town in his carriage … Every step was accompanied by the joyous and heartfelt cheers of an enthusiastic populace … Gay colours floated and bright faces beamed from every house and the streets were absolutely impeded by numbers of triumphal arches … After the procession had gone through the town, a grand dinner was held at the Cross Keys Inn … Altogether, nothing to equal the day’s celebration has been known in the history of the borough.

Following the 1841 election, attempts were made to increase the number of ‘ten-pounders’ eligible to vote. Both the Liberal and the Tory supporters let stables and sub-divided-buildings for letting to their supporters. Even empty property was broken into and occupied. A house in the High Street was simultaneously occupied by both parties and the resulting confrontation needed the Mayor reading the Riot Act to restore order.[18]

Despite his support of reform, during this Parliament in March 1844, John Martin inexplicably voted against a clause of the Factories Act to limit the working-day to twelve hours and against an amendment to reduce it to ten hours. Four other MPs voted in the same way and their action in effect stopped the bill becoming law.[19]

The next election was not until 1847. However, in February 1845 some fifty-eight Tewkesbury electors (of equal numbers of Tory and Liberal supporters) signed a petition “deeply deploring the evils attending contested Election” and proposed that while Dowdeswell and Martin were candidates they should be returned unopposed.[20]

to Expand

In the event Dowdeswell did not stand in the 1847 election due to “domestic afflictions”. In his place Viscount Lascelles was to represent the Tories, contesting Tewkesbury with John Martin and another Liberal, Humphrey Brown. A Birmingham Chartist, James Atkinson, also indicated that he would canvass the electors, but he withdrew, as did Lascelles after losing the show of hands. Martin and Brown were consequently returned unopposed without a formal poll being taken.21Martin’s wife Mary had died in 1843 and he married again in 1847 to Maria Henrietta Baillie, the daughter of Evans Hamilton Baillie, and had ten children by her. The family’s London home was in Berkeley Square, London, a household with some dozen servants. His country home was Upper Hall, Ledbury, on which he lavished much expense in creating a Victorian mansion and grounds – he employed fifteen gardeners there, along with many other servants.

The 1852 election certainly was contested – somewhat vigorously. Martin and Brown were opposed by a lawyer, entrepreneur and publisher, Edward William Cox, described as a “conservative free-trader” [22] (despite apparently being a supporter of the corn-laws). His campaign posters and addresses attacked his opponents for their support of electoral reform: “You will be disfranchised, your town will be ruined, and you will be ruined with it. Both Mr. Brown and Mr. Martin are supporters of the party that is pledged to the destruction of your Borough.”[23]

On several of his posters Cox announced that “Victory is Certain!” However, in the event, Cox lost the show of hands and demanded a poll. The electorate, numbering 370, gave 205 votes to Humphrey Brown, 189 to John Martin and 147 to Edward Cox.

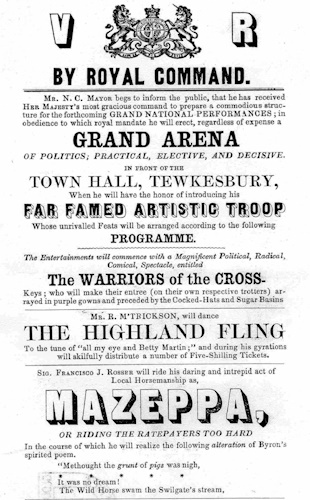

A satirical poster was published during the 1852 election by “Mr. Punch, of Tewkesbury”,[24] announcing the appearance at the Town Hall of the likes of:

Neddy Bray, or the Ass in the Lion’s Skin

he will jaw a horse’s hind leg off.

Mr. Jibb, the eminent Chartist Laureate illustrative of the talent, justice, and amiability of the Mobocracy.

Mr. Pumphrey Down will ride the high horse “Free Trade”.

The whole to conclude with a Grand Trial of Speed, Skill, and Power between

A British Game Cock, A Brown Linnett,

and a large Martingale.

Writing in the Gloucester Journal of 10 July, one reporter was not impressed by the proceedings, the press facilities, or the “musical promenade” at this election: “one cornet player, with a wooden leg, making such exertions that it was difficult to say whether the instrument or the man was most blown”.

Neither Martin nor Brown appear to have overburdened themselves with parliamentary work in this parliament. During a period in 1854, out of 92 divisions, they only attended 11 and 32 respectively.[25]

John Martin retained his seat in the 1857 election although he had fallen out with his fellow Liberal candidate Humphrey Brown over Brown’s involvement with the British Bank scandal. This caused a split in the Liberal ranks with Martin’s supporters refusing to use their second votes for Brown.[26] Although losing the ‘show of hands’ (as did Martin) the principal Tory candidate Frederick Lygon[27] was returned easily at the poll. The second Tory (Edward Cox again) needed the second votes of the Tories, but they were keen to see Humphrey Brown defeated. Brown commanded the majority of the Liberal votes and Martin needed around 70 of the Tory votes to turn things around. It was alle ged that this was achieved largely by the treating of voters to wine and cheese at the house of Martin’s agent, Mr. Winterbotham. The outcome was disputed when two electors com plained of bribery, ‘treating’ and undue influence by Martin and his agents. However, after a formal inquiry, the complaints were not upheld.[28]

Image: Part of a poster lampooning the elections, published during the 1852 General Election © Glos. Archives

In the same year, Martin suffered further inconvenience, this time of a physical kind when he fractured a rib while walking in London and coming into contact with the shaft of a cart.[29]

Prior to the 1859 election Martin announced that he would not be standing due to health problems. He stated that representing Tewkesbury “has been the pride and happiness of my life”.[30] This announcement led to some rumour that he was in fact going on to stand for election in Herefordshire. His agent, Samuel Healing, wrote to the county’s press[31] to confirm that Martin would not be a candidate in any other constituency and that his health was the sole reason for him standing down. His brother, James Martin, stood in his stead and was returned.

John Martin’s health problems appear to have been chronic, not immediately life-threatening, as he lived on for another 21 years. His second wife had died in 1865 at Upper Hall and John Martin died there on 7 March 1880.

The Tory-leaning Tewkesbury Register[32] printed a few lines announcing his death and recited the main facts of his life without comment. However, the Ledbury Free Press printed a lengthy obituary and description of the funeral.[33]

He was described as “one of the kindest friends that Ledbury has ever had … a man of unbounded philanthropy”. His “vigorous and unabated support” of National Schools established in that town was detailed along with his patronage of their Cottage Hospital. Mention was made of a private dispensary that he ran for the benefit of the poor, who received free treatment. He also supported the official Ledbury Dispensary. His work as a County Magistrate and Guardian of the Union was also praised.

The funeral took place on Tuesday 10 March, the body being deposited in the family vault in Eastnor Churchyard. The funeral procession started from Upper Hall, the funeral-car preceded by tenants of the Upper Hall estate on horseback. The coffin was covered with a violet silk velvet pall, trimmed with violet and white silk cord, and silk bullion fringe. The funeral car was drawn by four black Flemish horses. Over fifty tradesmen formed a double line on the Eastnor Road for the procession to pass through and again from the churchyard-gate to the church.

Herefordshire (Author 2011)Click Image

to Expand

At the conclusion of the service the Eastnor bells gave a muffled peal and, during the evening, similarly the Ledbury Church bells. Throughout the day the shutters of all the shops were partly closed in Ledbury.

The personal estate left in the will of John Martin amounted to £160,000.[34] That is around £8,500,000 in current values – and this figure does not include the value of his real estate property which would have been very substantial. (Upper Hall was valued at £20,000 in 1909 – £1,300,000 in current terms.[35])

So, a multi-millionaire like the vast majority of MPs of his time and a somewhat Dickensian figure. Perhaps more John Jarndyce of Bleak House than Samuel Pickwick of the Pickwick Papers? However, he did genuinely seek reform and directly aided those less fortunate than himself. Not some thing that can be said about many of his colleagues in Parliament.

References

- Bennett, Tewkesbury Yearly Register & Magazine for 1832 [Bennett’s Register]; James Bennett (1785-1856) bookseller, Freeman and historian of Tewkesbury: Cross Keys Inn, now Clinton’s Cards & HSBC Bank, 11-11a High St.

- Representation of the People Act 1832.

- Bennett, A List of the Poll, 1831.

- Extrapolated from figures in Bennett’s Register, 1831.

- Bennett, Bennett’s Register, 1831-34.

- Bennett, Bennett’s Register, 1831-34.

- Bennett, Bennett’s Register, 1831-34.

- Bennett, Bennett’s Register, 1831-34.

- Cobbett’s Weekly Political Register, 25 Oct 1806 & 5 Jun 1830: William Cobbett (1763-1835) polemical journalist and politician, originally a Radical Tory, then a Radical Reformer, MP for Oldham 1832-35.

- Bennett, Bennett’s Register, 1831-34.

- Bennett, Bennett’s Register, 1835-37; Gloucester Journal 24 Jan 1835.

- Bennett, Bennett’s Register, 1835-37.

- Gloucester Journal, 29 Jul 1837.

- Bennett, Bennett’s Register, 1835-37.

- Berrow’s Worcester Journal, 10 Aug 1837.

- Derek Benson, ‘Chartism in Tewkesbury and District’, THS Bulletin 19, 2010.

- Gloucester Journal, 10 Jul 1841.

- Bennett, Bennett’s Register, 1841 p.65: the Riot Act 1714 enabled authorities to order the dispersal of groups.

- Berrow’s Worcester Journal, 28 Mar 1844.

- Bennett, Bennett’s Register, 1845-47.

- Bennett, Bennett’s Register, 1831-34.

- Daily News, 1 Jul 1852; E.W. Cox (1809-1879) barrister, entrepreneur, publisher, editor of The Law Times.

- Gloucestershire Archives D2079/I/73 (See illustration 4.)

- Gloucestershire Archives D2079/I/73 (See illustration 4.)

- THS Woodard Database.

- See John Dixon, ‘Humphrey Brown MP’, THS Bulletin 13, 2004 for an account of Brown.

- Frederick Lygon (1830-1891) of Madresfield Court, 6th Earl Beauchamp.

- THS Woodard Database.

- Tewkesbury Weekly Record, 2 May 1857.

- Tewkesbury Register, 16 Apr 1859.

- Tewkesbury Register, 16 Apr 1859.

- Tewkesbury Register, 13 Mar 1880.

- Ledbury Free Press, 9 and 16 Mar 1880.

- National Probate Calendar.

- Gloucestershire Archives D2299/654.

![Charles Hanbury Tracy (1778-1858)<sup>[33]</sup>](/images/THS03629.jpg)

Comments