Chartism in Tewkesbury and District

And weary Parliament with ceaseless cries”

Ernest Charles Jones (1819-1869) Chartist and poet. Two lines from a long poem The New World

written in prison 1848-50, partly in his own blood on pages torn from a prayer-book

The Chartist Movement was at its most active during the decade 1838-1848 and was arguably the first mass working-class political movement that drew nationwide support. It grew out of discontent with several aspects of the condition of working people. Chiefly, the Reform Bill of 1832[1] had failed to provide the mass of workers with the vote or any significant new rights. The Corn Laws,[2] along with the protectionist economy, kept food prices high, and indirect taxation took a large part of the working man’s wages. Attempts to form effective trade unions were suppressed with dire consequences for activists such as the Tolpuddle Martyrs.[3] Furthermore the new Poor Law Act of 1834[4] abolished ‘outdoor relief’ replacing it with the workhouse.

Only freeholders and leaseholders of property worth £10 a year and wealthier tenant farmers had the franchise. Tewkesbury is a good example of ‘democracy’ at the time. In 1843 from a 6,000 population 445 could vote, and they returned two Members of Parliament.5 Before the 1832 reforms it was even worse: in 1831 at least half of the 387 voters were non-residents.6 The Reform Act increased the electorate by about 50% but still only one in seven adult males had the vote.

The London Working Men’s Association was established in 1836, primarily by William Lovett, Francis Place and Henry Hetherington. One of their key objectives was to obtain electoral reform. In pursuit of this they formulated six specific objectives which they drew up in a charter – hence the name ‘Chartists’.

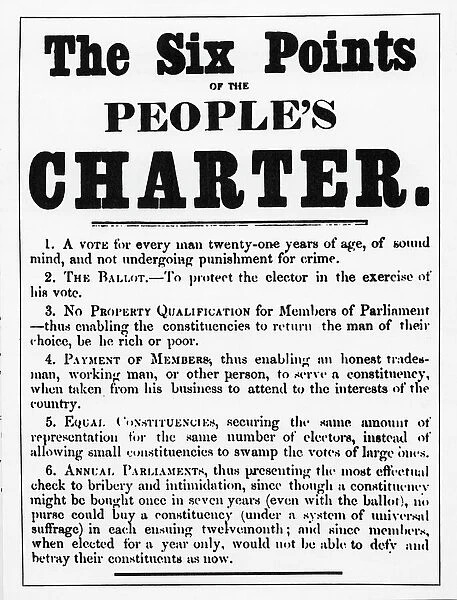

The People’s Charter

- Universal Manhood Suffrage.

- Vote by Secret Ballot.

- No Property Qualification for MPs

- Payment of Members.

- Equal Sized Voting Districts.

- Annual Parliaments.

The movement grew rapidly but was made up of diverse groups. Some were religious, often Methodists and other non-conformists; there was also a strong teetotal faction. One group believed that education of the working class was key to progress, another that land reform was important. Others were from specific reform groups such as the Anti-Poor-Law League, the Anti-Corn-Law League and the Ten-Hours Movement.[7] Many were Socialists and Trade Unionists (although the Trade Unions were often ambivalent in their attitude to Chartism). Some were decidedly middle class, like the Society for the Promotion of the Repeal of the Stamp Duties.[8] At one end of the Chartist political spectrum were radical Tories, at the other revolutionaries advocating violent struggle. Although the leadership was diverse, in general the rank-and-file were very much town-based artisans and workers. For some time they all rallied around the Charter, but their significant differences in outlook would greatly contribute to the eventual breakdown of the movement.

To promote the Charter, mass-petitions were organised, National Conventions held, newspapers published, and tours arranged of speakers dubbed ‘missionaries’ who encouraged the formation of local Working Men’s Associations.

A Chartist presence in Tewkesbury was formally established with a visit by the important Chartist leader Henry Vincent. He arrived on 12 March 1839 with another missionary William Burns. In his diary Vincent described Tewkesbury as “a clean and neatly built town … with a very handsome church … the manufactories are principally hosiery and lace.” He called upon Mr. Craig, a leather-seller, who politely told him that he supported household suffrage, was not a Chartist, and did not know of any Chartists in the town.[9] This was probably John Craig of Barton Street, a Scotsman, aged about 50 in 1839 – he already had the vote.[10]

Vincent then walked over to the (possibly Temperance) Queens Arms, described by him as “a complete palace of an inn”. The landlord, “Mr. Pearse”, told Vincent that he was himself a Radical and let him a large room for a meeting that evening. This would be Samuel Pearse, then aged about 40:[11] he was bankrupted in 1843 after having borrowed £2,000 on an inn.[12]The Queens Arms is thought to be what is now the Berkeley Arms in Church Street. However, the 1841 census places ‘Samuel Pearse – Inn Keeper’ two houses away from ‘Osborne – Grocer’, between ‘Tunnicliff – Surgeon’ and ‘Holland – Butcher’. Osborne’s and Tunnicliff’s were the buildings now seen to the left of the Methodist Church; the Berkeley Arms is the fourth from the church on the right. The Berkeley Arms is an extremely nice, quite small public house, but perhaps not a ‘palace of an inn’ with a ‘large room’? Perhaps the Queens Arms was a building demolished to make way for the church in 1878?

Again from Vincent’s diary, we learn that while he was at the inn two working men entered and were found to be readers of the Northern Star,[13] the leading Chartist newspaper. Their support was offered for the meeting. The ‘bellman’ (town-crier) was sent for and asked to publicise the meeting, but he told them that he had been forbidden by the Town Clerk to do so. Pearse then produced a bell and a “tall Masaniello-looking fellow”[14] from the Quay was engaged to ‘cry’ the meeting.

At around six o’clock that evening about seventeen “friends” arrived from Cheltenham having walked twelve miles from there. Vincent and Burns had spoken in Cheltenham the previous week to large crowds. The arrivals brought news that since then 65 new members had been recruited to their Working Men’s Association: formed in late 1837, the first formal Chartist organisation in Gloucestershire.The meeting commenced at seven o’clock, reportedly attended by about 450 people. Vincent’s speech that evening was interrupted by what he described as “one of the ‘intelligent’ constituency”, “a member of the ‘legal profession’ … appropriately drunk”. The heckler argued that he was against the extension of the suffrage due to the drunkenness and immorality of the people. Vincent said he thought the “gentleman” would just suit the House of Commons and that he had never seen a finer subject for a “member”. However, the Gloucester Journal[15] gives a different version of events: “A sturdy Conservative, (whose absence might have been more prudent,) cried out ‘You are deceived’ … was instantly expelled … ill-treated … left almost in a state of nudity!”

At the conclusion of the meeting the Charter was unanimously adopted and a society formed called The Tewkesbury Working Men’s Association; 10/- [50p.] was collected towards funds. Three cheers were given to Vincent and Burns, three to the Chartist Convention, and three for themselves, their wives and sweethearts. The meeting broke up and Vincent “retired to bed, very fatigued at twelve o’clock.”

James Bennett commented on Vincent’s visit in his 1839 Register. He described him as “the notorious chartist delegate … afterwards convicted of sedition and conspiracy”, and reports the meeting as being “a long harangue … abusing the parliament and the clergy”, with Vincent insisting that universal suffrage and the secret ballot would be “a panacea to all their ills, social and political.”

Although Henry Vincent was a militant at this time, he later became a leading member of the ‘Moral Force’ faction of the movement as opposed to the ‘Physical Force’ faction. He also became a leading member of the Teetotal Chartists, and in later life he was a chapel lay-preacher, anti-slavery campaigner and stood unsuccessfully for Parliament several times.

However, 1839 was a difficult year for him. In April he was badly assaulted in Devizes and was arrested in May accused of having participated in a riotous assembly in Newport. Despite evidence from the chief prosecution witnesses that he had in fact told the people to disperse quietly and to keep the peace, he was found guilty and sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment. While he was in prison the serious attempt at insurrection known as the ‘Newport Rising’ took place, with Vincent’s plight being a key factor. On the night of November 3-4, at least a thousand people,[16] many of them miners, marched on Newport with weapons. One of their objectives was to storm the Westgate Hotel where they thought political prisoners were being held – including Vincent. They were met by about 60 soldiers and 500 special constables and in the ensuing battle shots were fired by both sides: 24 of the rebels were killed or died from their injuries and about 50 more were wounded; one soldier was seriously injured along with two of the special constables. In the aftermath 200 or more Chartists were arrested and 21 were charged with high treason. The three main leaders were sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered – this was commuted to transportation for life. One of the three was John Frost;[17] he had planned to speak in Tewkesbury the previous June but failed to appear, much to the satisfaction of James Bennett. The latter supposed that Frost was unable to attend as he “was so busily engaged in maturing his plans for the premeditated attack on Newport.”[18] Nevertheless, in a petition from Cheltenham to spare the lives of the three leaders, 305 of the 7,820 signatures were from Tewkesbury.[19] Despite being incarcerated in Monmouth gaol at the time of this event Vincent was one of those charged with conspiring with John Frost “to subvert the constituted authorities and alter by force the constitution of the country.” He was convicted and sentenced to a further 12 months’ imprisonment.

The Working Men’s Association set up in Tewkesbury following Vincent’s visit was led by William Morris Moore, a one-time commercial traveller, then a stockinger and Methodist lay-preacher who lived in Jeynes Row. Moore was born in Hathern, Leicestershire in 1813, the son of William and Elizabeth Moore. He is thought to have spent some years as a youth in Belgium and France. On 23 July 1839 he wrote as Secretary of the Association to the editors of the Northern Star[20]describing the financial situation of the 700 stockingers in Tewkesbury. They earned about 6s.[30p] a week and, after deducting work-related expenses, they were left with around 3s. per week to live on. In consequence he states that many of them had become Chartists, although “we meet with decided opposition, and even persecution in every shape and form.” The letter tells us that meetings of the association were held each Monday and their motto was “universal suffrage and no surrender.” Lofty resolutions were passed, such as one on 15 July 1839 condemning “the recent outrages and bloody proceedings of an unconstitutional and blood-thirsty force from London against the peaceable inhabitants of Birmingham[21] … proof that the administration of justice is the last thought of the practically infidel Whig government” (indicative of the Chartist view of the ongoing ‘Great Whig Betrayal’). While pledging the Association’s unqualified support of the National Convention and their desire to assist in every way, they regretted that because of their poor condition they could not offer financial aid. The letter also notes that “We are not a little proud that our respected member, John Martin, Esq. voted for the National Petition.”22

In the same issue of the Northern Star there is a letter from an Eliza Hale, secretary of a “Female Radical Association” based in the Borough of Tewkesbury. Although she describes the association as “few in number” the letter says that they met weekly and states their determination “to assist our dear sisters in different parts of our beloved country, in their attempts to obtain for them and their husbands, brothers and sweethearts – Universal Suffrage.”

Bennett’s Register tells us that the Chartists met in a hired room in Church Street and that they held frequent Sunday open-air meetings on the outskirts of the town. We know from a local radical newspaper that William Moore had a busy month in September 1839.[23] He preached a sermon at the Oldbury in Tewkesbury on 4 September. A few days later he spoke in Cheltenham (with special constables present) and apologised for speaking wearing his hat as he had a very bad cold! On the 15th he preached to 2,000 people in Cirencester (where fighting broke out); on the 22nd in Charlton Kings, and on the 29th to a large crowd in Winchcombe. We learn something of the establishment’s attitude to the Tewkesbury Working Men’s Association and its Secretary from the Cheltenham Examiner,[24] “… it was asserted that 189 Chartists were enrolled in the Working Men’s Association; now, however, their numbers have dwindled below fifty … their fund is barely sufficient to defray the expenses of the room in which they meet … Their secretary has been spouting at Cheltenham and Winchcombe and other places in the vicinity … he was dismissed from the society of the Tewkesbury Tee-Totallers, for wishing to disseminate his rancourous principles … insulted one of our most respectable inhabitants … ”

Indeed, there were links between Teetotallers in Tewkesbury and the Chartists; the aforementioned Queens Arms hosted Temperance Meetings. A Temperance Society had been formed in 1834 but appears to have been superseded by a more ‘hard-line’ organisation whose motto was “Moderation is the half-way house to Intoxication.” Then on 16 March 1841 the Victoria Temperance Hotel opened near the centre of Church Street in a large house previously the residence of John Allis, a Quaker. (Interestingly in a Gloucester newspaper, accompanying a report on the opening of the hotel, is an item stating that a “strong petition” against the New Poor Law Bill received 1,200 signatures in Tewkesbury.)[25] However, by early 1843 the hotel appears to have declined, “its gaudy sign-board taken down”. John Hill ran the hotel and delivered lectures on Teetotalism, but he also spoke in support of Chartism. In 1846 he died in Birmingham; according to Bennett he had become “a votary and ardent admirer of Bacchus.” The Temperance Movement in Tewkesbury had 200 members at its peak but this number had declined to a dozen or so at its demise.[26]

In August 1839 the Chartists in Cheltenham declared that they would “invade” St. Mary’s Church, Cheltenham. This was the centre of power of the Rev. Francis Close[27] and was regarded by the Chartists as the church of their supposedly social betters. Their intention was to attend the church in numbers (reportedly 500 or so) to register dissatisfaction with what they saw as the hypocrisy of many ‘established-church Christians’. They duly arrived along with some Tewkesbury Chartists on 18 August. Rev. Close had prepared his sermon for them and he used it to attack the Chartists, warning them against “the tyranny of mob rule”. He criticised them for ingratitude in the face of so much local charity, and declared that “Socialism was rebellion against God and Chartism rebellion against man”. However, he did commend them on their orderly conduct. The Chartists then left the church during the playing of the National Anthem.

The Chartists reassembled in a field on the London Road and in answer to Close, Tewkesbury’s William Moore preached to a crowd estimated at 1,000–2,000. After prayers and the singing of two hymns from Wesley’s hymn book, he answered the theological arguments that Rev. Close had used. He went on to criticise the Corn Laws and to place the blame for their present distress on “ … all the bad legislation of the Whig aristocrats”. He urged the crowd to “ … reject Reverend Close and go for the People’s Charter.” He also alluded to his youth spent in Belgium and France and emphasised the need for moral protest, to obey the law, and not to commit rash acts against the authorities.[28]

A week later, wives and other female Chartists staged a similar ‘sit-in’ at St. Mary’s.[29] Close told them not to attempt “ … the removal of sufferings which were inherent in the nature of humanity” and “to stay at home”. He went on to compare them to women of the French Revolution, as having “dehumanised themselves into fiends akin to their French sisters”. On the same day about 30 Tewkesbury Chartists attended the Tewkesbury Abbey morning service although this ‘invasion’ appears to have been uneventful.[30] It was expected that a similar visit would be made to Trinity Church, Tewkesbury, but it did not take place. This frustrated the Rev. Edward Foley who noted on a published copy of Close’s sermon to the Chartists, “They promised me a visit at Trinity Church on the following Sunday, but thought better of it, to my disappointment, as I was ready for them .”[31] The sermon that Moore preached at London Road apparently led to Francis Close making derogatory comments concerning its content and the character of the preacher. Moore answered the attack in an open letter to Rev. Close published in the Cheltenham Free Press on 7 September 1839. He asks for justification that his sermon was blasphemous and the grounds for Close calling him “a drunken, idle, and dissolute fellow”. He also denies being expelled for drunkenness from the “Tewkesbury Tee-total Society”. He goes on to offer to debate in public with Close the rational and biblical character of Chartist principles, “though I am comparatively illiterate, [I] am a member of the Working-classes …” (Yet in a speech in June, he cryptically said that he “had been born among the higher classes.”)

We learn a little more of William Morris Moore when, in October 1839, he spoke at a ‘Chartist Tea Party’ at the Emporium, Cheltenham. Around 400 guests were present: “among whom were many of the fairer half of creation … Recitations, songs and sentiments were given between the speeches ... and the remainder of the evening was passed in dancing.”[33] Such socials were a common component of Chartist activities along with lectures, libraries and other education facilities for working people.

An example of the effort to educate was the Mechanics Institute that met in the Presbyterian Chapel in Albion Street, Cheltenham: formed to spread “knowledge among the mechanical portions of the town.” The Reverend Close set up his own Working Men’s Association in rooms in St. George’s Place as a “literary and scientific institute for the humbler classes.” This was no doubt intended to rival the Chartist dominated Mechanics Institute. It was at the Institute on 24 May 1842 that George Jacob Holyoake delivered an innocently titled lecture Home Colonization as a Means of Superseding Poor Laws and Emigration. However, questions from the audience (some thought to be from journalists from the Cheltenham Chronicle) provoked Holyoake to make comments on religion. When asked by a local preacher named Maitland what their duty to God was and whether there would be churches and chapels in his community, his reply included comments that: “we are too poor to have a God and build churches … Morality I regard, but I do not believe there is such a thing as God.”[34]

His remarks were heavily reported in the Cheltenham Chronicle – a newspaper that Rev. Close had interest in and that stoutly supported him. It is believed likely that Francis Close was instrumental in bringing these comments to the notice of the magistrates and Holyoake was arrested for blasphemy. Conducting his own defence, he spoke for nine hours! Perhaps he would have made his point if he had limited himself to one statement that he made during that time, “Christianity says we are all brethren, but I like not that equality which allows one man to revel in his opinions – while others are punished with imprisonment in gaol for thinking theirs.” He was found guilty and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment. He was further punished when he refused to attend the Gloucester Prison Chapel prayer meeting: “You can not expect me to come to prayers; you imprison me here on the ground that I do not believe in a god, and then you would take me to chapel to pray to one. I cannot prevent your imprisoning me, but I can prevent your making me a hypocrite.”

Back in Tewkesbury the Working Men’s Association soon ran into problems. Bennett informs us that in November 1839 the Secretary and Treasurer of the association absconded with the society’s funds and added that Moore had betrayed his clerk for a “trifling reward”.[35] A Cheltenham Free Press correspondent concurred, adding that “the revolutionary tide is happily checked in this vicinity.” The article also stated that Moore was “recently furnished with a suit of clothes by the Chartists of Cheltenham”, and that his licence to preach had been purchased for him by Tewkesbury’s framework knitters. In October the Free Press had reported that Moore had been ill but was on the mend.[36] In any event the next we hear of him is when he is resident in Tewkesbury Workhouse as recorded on the 1841 census.[37] He died there of consumption on 21 July 1841 aged 28 and was buried in Tewkesbury three days later. He allegedly left a deathbed recantation of his Chartist involvement and this testimony was published in newspapers and pamphlets nationwide.

“I here solemnly declare on what I expect soon to be my dying bed, and before that God in whose presence I expect shortly to stand a naked spirit, that I repent of ever joining the Chartist Association. Little did I think I was going to surround myself with men of principles so contrary to those of pure religion. Oh, that I had listened to Christian advice! And now I wish it to be known throughout Tewkesbury and the neighbourhood, that I sincerely regret having so awfully prostituted the Word of God, as I did by getting people together on blessed Sabbath days, and preaching sermons three parts politics, and the rest a little less than scepticism. And if I did, as it is feared I did, lead any one astray by my influence, I hope they may hear these my dying words, and immediately, by Divine mercy, return to the paths of life. And as for some of those who were my principal associates, and whose infidelity has even prompted them to oppose ministers of the truth of God, I pray you to take warning before it is too late. Were you in my circumstances, I trust you would think and feel differently, but I assure you that if you die as you are, five minutes’ suffering under the vengeance of an angry God will take away all your infidelity. Take warning; and may the Lord have mercy upon your souls!

(Signed) William Morris Moore, Tewkesbury Union Workhouse, July 7 1841.” [38]

Wherever this was published it states that this was an “extract of the more important part” of his declaration. The full text was published in the Cheltenham Free Press[39] and the omitted parts are mainly religious in nature, although there is a tribute to the master of the workhouse for his “great kindness”. However, the newspaper states that “we have some doubts of its genuineness” and asks its readers to judge for themselves. Certainly, the obsequious, ‘show-trial type confession’ that was printed provided very good ammunition for anti-Chartist interests. The Free Press describes pamphlet versions of it being hawked on the streets as “the last dying confession of the wicked Charterist, Moore.”

The publication of the tract triggered correspondence in the local newspapers.[40] Francis Hayes of the Cheltenham Mechanics Institute appears to have known Moore well and questions the testimony. He adds that Moore was expelled from the Teetotal Society for forming the Tewkesbury Working Men’s Association, not for being drunk.

Hayes’s letter was answered by “A Lover of Truth” from Tewkesbury – could this be Bennett? The ‘truth lover’ includes a letter from the father of Moore confirming that the confession was the true sentiments of his son. Hayes replied questioning the motives and character of an anonymous writer and added that Moore had often told him of the “injustice of the father to his children”. Certainly the letter is suspiciously well written for an apparent framework knitter living in Well Alley.[41]

“Tewkesbury, August 11th 1841

Sir – Having been with my son very frequently during the latter stages of his illness, I can bear full testimony that the statements already published by you were his true sentiments and, having myself been too, much disposed to take up Chartist principles, I would take this opportunity in hoping, that all who have been so led astray, may take warning from the dying testimony of my son. I am sir your humble servant. William Morris”

It is worth noting that the Free Press article of 7 August 1841 corrects a statement they had made that Moore had run away with the money-box of the Tewkesbury Working Men’s Association. They now accepted that the Tewkesbury Chartists had no funds at the time that Moore left the town.

Bennett directly commented on Moore’s death in his 1841 Register, describing him as “an itinerant Chartist preacher of some celebrity” and attributed his politics to “the fevered notions of ‘liberty and equality’, which he had imbibed in France.”

On the national scene, Feargus O’Connor was arguably the most important Chartist leader – certainly the most self-important. Although far from being a Socialist, he envisaged co-operative style farming communities of cottages with smallholdings. In pursuit of his Utopian vision he formed in 1845 the Cooperative Land Society, later known as the National Land Company. The basic idea of his scheme was for working people to buy shares in the company, the money to be used to buy land and build cottages. Shareholders would then be chosen by ballot to live and farm in these communities. They were to pay rent which was to be used to repay (in theory with interest) all the subscribers.

One such community was Snig’s End: it consisted of 268 acres lying partly in Staunton and partly in Corse, some nine miles south-west of Tewkesbury. By 1848 a schoolhouse and 85 four-roomed, single-storied cottages had been built, each with three or four acres of land. It is claimed that the third Chartist Petition was taken to Parliament in 1848 on a cart made at Snig’s End and pulled by estate horses; O’Connor himself lived there for some time after 1848.

In the 1851 census we can see that some 20 families made up the Snig’s End community, each farming from two to six acres. They were from all over the country with most of the heads of households in their thirties though several were in their fifties.[42] Although they no doubt welcomed the chance of living in well-built housing, having land to farm and a school for their children, the change from being perhaps a factory worker in Lancashire transplanted to farm in isolated countryside must have been challenging.

formerly Chartist schoolhouse (Derek Benson 2009)Click Image

to Expand

Ultimately the settlements were not a success, and the tenants had difficulty in making a living and resisted paying their rent. The government attacked the scheme by branding it an illegal lottery, and in 1848 the House of Commons set up a Select Committee to look into the company. It declared that The National Land Company was an illegal scheme that would not fulfil the expectations held out to its shareholders. After a number of court cases an Act to wind-up the company was passed by Parliament in July 1851. The settled shareholders mostly disappear from the records of most of the estates in the years following, and the estates themselves were auctioned off. However, at Snig’s End several of the 1851 tenants were still there in 1861[43] and today the cottages are sought after residences; the school became The Prince of Wales public house.

In July 1847 O’Connor had been elected as MP for Nottingham but his mental health was deteriorating, no doubt exacerbated by his heavy drinking and possibly syphilis. In August 1849 he wrote a strange letter to Queen Victoria beginning “Well Beloved Cousin” and signing himself as “Your Majesty’s Cousin, Feargus, Rex, by the Grace of the People”. In 1852 he struck two fellow MPs in Parliament, and at the Lyceum Theatre, a policeman. In June 1852, he was admitted to an asylum at Chiswick. As news circulated that he was neglected and in need, working people contributed to a fund to help him. O’Connor died on 30 August 1855 at his sister’s home in London. Fifty thousand people were reported to have attended his funeral.

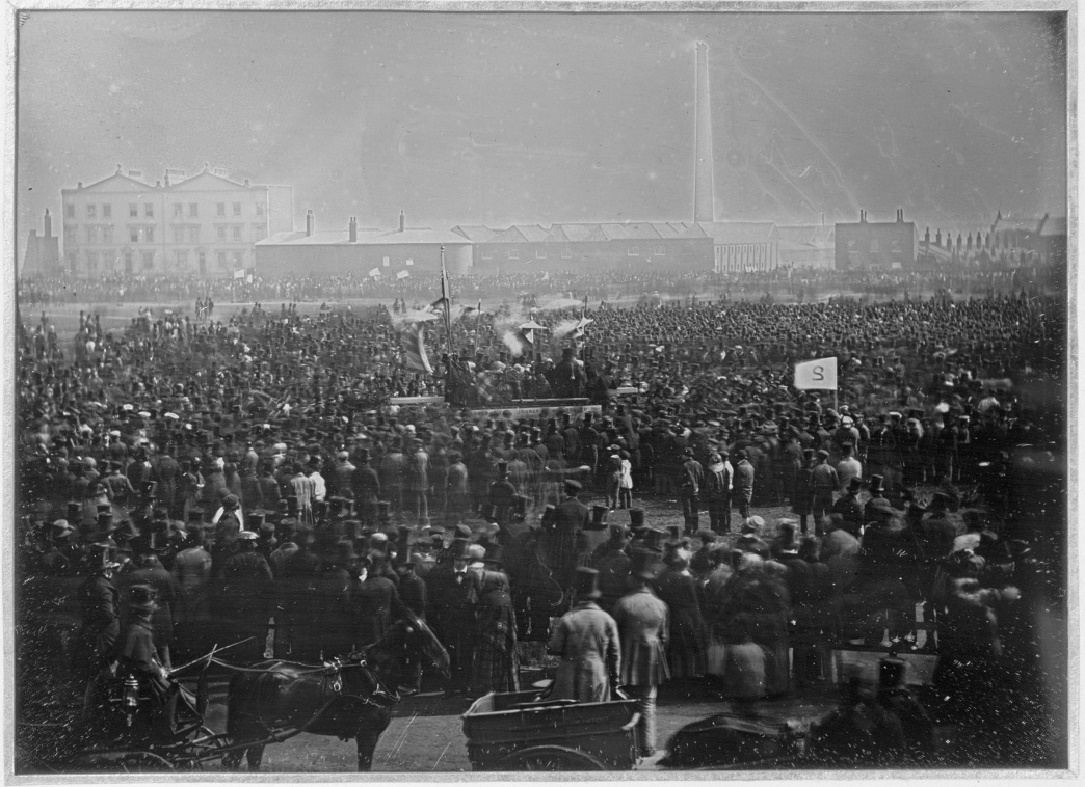

Chartism as a significant force can be said to have ended in April 1848 when the third Chartist Petition was delivered to Parliament. It was claimed to have had nearly six million signatures but the actual number was much smaller and many of those were obvious forgeries. The plan was to deliver it after a mass meeting on Kennington Common and a march on Parliament; the march did not take place and the meeting was considered a failure. Following the rejection of the petition by Parliament (222-17) widespread disturbances throughout the country occurred and many Chartists were arrested. The 1848 Chartist National Convention dissolved into acrimony and division.

However, the movement did continue in various guises into the 1850s, developing a radical program. The 1851 Convention proposed (amongst other things) the nationalisation of land, free education, the right of the poor to relief and the abolition of capital punishment. Many Chartists turned to other endeavours. Local Government, the Cooperative Movement and Trade Unionism; others agitated for reforms in education, some joined the Temperance Movement, a number moved towards Marxism. Of the original aims of the Charter, only that of annual elections has not been realised. The property qualification for MPs was abolished in 1858, and the secret ballot introduced in 1872. MPs were paid from 1911, and successive Reform Acts equalised electoral districts. The advent of universal suffrage for all men in 1918, and then for all women in 1928, is something that would have gratified and exceeded the expectations of the Tewkesbury Chartists, and their comrades in the district and elsewhere.

How significant was the role of the people of Tewkesbury in the Chartist Movement in Gloucestershire? Certainly not as involved as those of Cheltenham where the Chartists were particularly active. Nevertheless, the penurious stocking-workers of Tewkesbury no doubt made archetypal Chartist ‘foot soldiers’. Furthermore, the preaching throughout the county of Tewkesbury’s William Morris Moore drew crowds of thousands. When ailing on his deathbed it could be that he did repudiate his Chartist agitation. However, opponents of the movement may well have embellished his words for propaganda purposes; this may also be the case with the exact facts surrounding the various misdemeanours attributed to him. In any event the widespread publication of his alleged recantation is in itself indicative of his importance. William Morris Moore was clearly a far more prominent and interesting character from Tewkesbury's political and religious past than Bennett would have us believe, with his curt dismissal of him as an “itinerant Chartist preacher”.

10 April 1848 (William Kilburn)

The Royal Collection ©2009,

Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II.

Postscript

I was prompted to write this article on discovery that Frederick Tovey of Cheltenham, ancestor of Janet Martin (THS Secretary), was a nominee to the General Council of the Chartist National Convention in 1842.References

- Representation of the People Act 1832, enacted by the Whig government in the face of severe opposition.

- Import tariffs on foreign corn, keeping the price of domestic corn artificially high.

- In 1834 six Dorset Agricultural Labourers were sentenced to seven years transportation for taking an ‘illegal oath’ when they formed a ‘friendly society’.

- Poor Law Amendment Act 1834, replacing the old, mostly 17th century, parish based ‘Poor Law’.

- James Bennett, Tewkesbury Yearly Register & Magazine (Bennett’s Register) for 1843.

- Dr. Anthea Jones, ‘Tewkesbury’s M.P.s’, THS Bulletin 5, 1996.

The Anti-Poor Law League was formed largely by Tory Radicals following the 1834 Poor Law Amendment Act.

The Anti-Corn Law League, formed in 1838 by Richard Cobden and John Bright. Corn-laws were abolished in 1846. - The Ten-Hours Movement was formed in 1831 to campaign for factory reform, led by Richard Oastler.

- The Society for the Promotion of the Repeal of the Stamp Duties, to remove newspaper taxes, led by Francis Place.

- Henry Vincent, Life & Rambles, https://www.visionofbritain.org.uk/text/chap_page.jsp?t_id=Vincent&c_id=3

- Woodard Database, 1832 Poll List.

- 1841 census HO 107/380/6 es.7 p8.

- Woodard Database – Linnell, Tewkesbury Pubs. (Unclear whether the inn was the Queens Arms or the Quart Pot.)

- Northern Star and Leeds General Advertiser (Northern Star), established by William Hill, Joshua Hobson and Feargus O’Connor in 1837.

- Alias of Tommaso Aniello, the 17th century leader of an insurrection in Naples against Spanish rule.

- Gloucester Journal founded 1722 by Robert Raikes and William Dicey.

- The exact number is unclear. Up to 8,000 assembled in the area but a much smaller number actually participated in the attack on Newport.

- John Frost (1784-1877) Draper, Newport Town Councillor, Mayor and Magistrate – and prominent Chartist.

- Bennett’s Register for 1839, Vol. I p.427.

- Gloucester Journal 8 Feb 1840.

- Northern Star 3 Aug 1839.

- Birmingham ‘Bull Ring Riot’ 4-5 Jul 1839. Police brought in from London to clear a crowd deemed to be an illegal assembly. Chartist leaders were arrested in the aftermath.

- John Martin of Upper Hall, Ledbury (1805-1880). Whig (Liberal) M.P. for Tewkesbury 1835-1859. First Chartist Petition presented to Parliament 7 May 1839, rejected by 235 votes to 46. (Martin did not vote for later Petitions.)

- Cheltenham Free Press 14 , 21 Sep & 5 Oct 1839, (est. 1834 , incorporated with Cheltenham Examiner 1908).

- Cheltenham Examiner 21 Aug 1839, (est. 17 July 1839, incorporated with the Gloucester Journal in 1913).

- Gloucester Journal 20 Mar 1841.

- Bennett’s Register, 1838-1846.

- Rev. Francis Close (1797-1882), later Dean of Carlisle (‘Dean Close’). Anti-Chartism – and anti many other things.

- Owen Ashton, 1983, Clerical Control and Radical Responses in Cheltenham Spa 1838-1848: Midland History, 8.

- a. Ian McCalman, 1999, An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age: Oxford University Press; b. Owen, above.

- Bennett’s Register for 1839, Vol. I, p.427.

- Gloucestershire Archives, P329/2 in 4/1/1. Rev. Edward Walwyn Foley incumbent of Trinity Church.

- Cheltenham Free Press 8 Jun 1839.

- Northern Star 26 Oct 1839.

- a. George Holyoake, 1871, The Last Trial for Atheism; b. Ashton, as in fn. 28 above.

- Bennett’s Register for 1839, Vol. I, p.426.

- Cheltenham Free Press 23 Nov 1839 & 26 Oct 1839.

- 1841 census HO 107/380/7 es.7 p.4.

- Freeman's Journal and Daily Commercial Advertiser (Dublin, Ireland) 13 Aug 1841.

- Cheltenham Free Press 31 Jul 1841.

- Cheltenham Free Press 7 , 14 & 21 Aug 1841.

- 1851 census HO 107/1974 f.344 p.5.

- 1851 census HO107/1960 f.430-432.

- 1861 census RG9/1762 f.49-50.

Comments