A Serving of Metropolitan Culture in Eighteenth-Century Tewkesbury

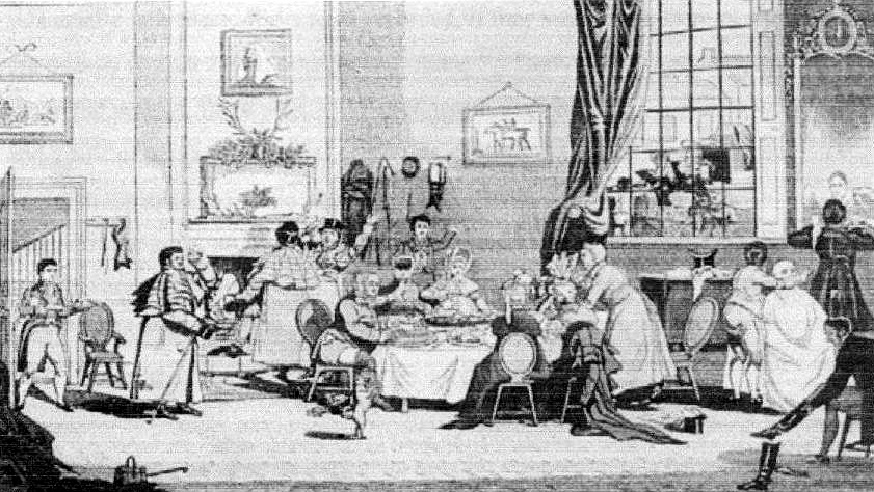

Illustrations of the interiors of inns during the early modern period are rare. However, J. Green’s print, Eating at a Country Inn21 from the early nineteenth century, contains many elements that would have been found in Cotton’s inn. As the print is from a later period, it indicates that Cotton’s inn was advanced for its date. There are fashionably dressed people, numerous tables and chairs, and decorative objects such as window curtains, looking glasses and pictures.

Tewkesbury has a history of ancient public houses providing drink and victuals to locals and travellers alike. Angus Patterson argues that inns’ “ancient and proper use”, according to an English Act of 1606, was “for the receipt, relief and lodging of wayfaring people”.[1] In 1533, four inns and fifteen taverns were recorded. By 1820, this had grown to nine inns and sixteen taverns.[2] Many of Tewkesbury’s premises are discussed in B.R. Linnell’s 1996 book Tewkesbury Pubs,[3] which records the names of the inns and inn-holders from the last quarter of the eighteenth century up to recent times. In Gloucester Archives, there are surviving documents that allow us a glimpse into the trade of inn-keeping for the early modern period. Innkeepers were usually from the ranks of the middling sort and had responsible roles in their communities.[4] There are a number of probate inventories that shed light on how these businesses were operated as they often listed the movable goods that were owned at the time of the inn-holder’s death. These documents were made to assist the proving of wills, and exist for most trades, and for members of the gentry. Although there are inventories for a number of Tewkesbury inn-holders, many being transcribed by Bill Rennison and Cameron Talbot,[5] the inventory of Thomas Cotton made in 1733[6] stands out from the majority. This is due to its being recorded in a detailed manner, which allows us to see all the objects in each room of the premises. In addition, Cotton was a wealthy man, and his goods were noteworthy. The inventory contains an unusual amount of new fashionable commodities, but he was also aware of the new hot drinks that were only beginning to be adopted in towns outside the metropolis. The document illustrates that some eighteenth-century Tewkesburians were living refined and genteel lifestyles, most likely due to having links with London that kept them informed of new fashions and the accompanying polite behaviour.

Apart from Thomas Cotton’s possessions nothing is known about the man or his family. There is no surviving will, and there do not appear to be any taxation schedules that would reveal the part of town in which he had lived, or the name of the inn. Cotton was not a common Tewkesbury surname; the father and son of the same name, recorded in Norah Day’s list of Freemen in 1686, were bakers.[7] As the elder Freeman’s name was also Thomas Cotton, there may be a possibility this was a family member, for example, grandfather, father or uncle. Thomas Cotton, the inn-holder, did not appear to have played an active role in the town as did many wealthy, middle-ranking men. He was not recorded as serving an apprenticeship, or being a Freeman. There is no evidence to suggest that Cotton had held a position in Tewkesbury’s Corporation, at a time when involvement in local government provided a career structure for men who sought status and influence in the Borough.[8]

What is known about Cotton is that he owned a many-roomed large quality inn, of unknown name and location. As these details were known to the probate assessor who wrote the inventory, there was no reason to record them. The inn would have been on an important street, due to its great size and wealth. Anthea Jones argues that, during the eighteenth century, “in each of Tewkesbury’s main streets was one major inn.”[9] These were The Star and Garter[10] in Barton Street, The Royal Hop Pole Hotel[11] in Church Street and The Swan[12] in the High Street. It is possible that Cotton’s inn was one of these large establishments.[13] The inn would have appealed to more affluent members of society, people from the middling ranks and above, or wealthy travellers. Angela McShane Jones suggests that taverns and inns were often the largest public buildings in a market town embellished far beyond the modest amenities of home.[14] The pleasant surroundings would have been a suitable venue to conduct business. There is no evidence that entertainments were provided, as found in other inns. At the time, these were games like backgammon, and shuffleboard,[15] or more violent sports like cock fighting.[16] The idea of treating animals with kindness would have been an almost unheard of notion, as they were required for specific purposes. Cotton had two ‘dog wheels’, one in his kitchen, and the other in a room that fronted the road. These were labour-saving devices that freed a servant from the monotony of turning a spit in front of a fire. A small dog was put in a drum with a hot ember to make it run, this turned the spit.

The inn contained fifteen rooms and a stable and brewhouse. Beer and ale sustained existence at a time when water was dangerous to drink..[17] B.R. Linnell argues that it was usual for landlords to have a basic trade they laboured in during the day, whilst their wives tended the bar: it was “unlikely that the beer-house alone supported the family”.[18] This did not appear to be the case here, since the combination of supplying quality food, drink and accommodation made the inn a profitable business. Cotton’s movable goods were valued at £605, a large sum of money. In comparison the goods of a Tewkesbury goldsmith, Samuel Jefferies, who also left an inventory from the same year, were assessed at £86.3s.5d. [£86.17p].[19] Cotton kept his inn well-stocked with a small fortune in alcoholic drink. He had £60 of exotic wine to supply to his patrons. At this time this was imported from the Rhineland and the Canary Islands. Wine was heavily taxed and was probably drunk only by the wealthy. Cotton also had £56.10s.0d. [£56.50p] of bottled cider, and thirty casks of ale with some cheese assessed at £55. What were not present were stocks of spirits as brandy was, by then, becoming a fashionable drink.

At this time customers were generally served drinks in traditional pewter quarts and pints, but the inn was also using a material that was to become increasingly sophisticated over the century; early pottery quarts and pints.[20] These could also have been used for hot beverages. Cotton supplied the latest novelty drink at his inn: tea. This had its own specialised equipage, ‘small earthen tea dishes’ were listed. These would have been functional and roughly made, far removed from the delicate and elegant porcelain that would later be available. Another indication that Cotton catered for his patrons’ changing tastes was the presence of numerous knives and forks: three dozen in total. The existence of cutlery indicates a behaviour shift, firstly that forks appeared, as the use of knives and forks, and its accompanying new style of eating, required a modification of existing practices away from eating food with a knife and fingers.[22] Pottage, eaten with a spoon, was an exception.[23] Secondly, the inn did not presume that customers brought their own knives and forks, as had been the custom up until at least the late seventeenth century. “Forks became standard equipment for the aristocracy in the 1670s.”[24]

A feature of Cotton’s inn was the unusual amount of decorative goods that he owned. At a time when many middling rank homes contained mostly functional goods, Cotton owned commodities that suggested an awareness of metropolitan fashion. However, it also hinted the owner had wealth and taste. These were objects such as looking glasses, chinaware, window curtains, clocks and pictures. It was more common for well-off people to own one or two of these objects - but Cotton had all of them. The public area of the inn, “ye little parlour, ye hall” and “ye club room”, had pictures (most likely cheap prints) and looking glasses. The bulk of the luxury goods were in the rooms above the inn where Cotton would have lived with his family: this was common for inn-holders in the early modern period. The upstairs bedroom suites were sheer opulence compared with the homes of many Tewkesbury residents, especially those who lived in the numerous overcrowded alleys, where they would have worked, eaten and slept in one or two rooms with only basic goods and necessities. The five sumptuous rooms, that were Cotton’s living quarters, were rented out to exclusive customers. This allowed concepts that are taken for granted in modern times, but that were only beginning to emerge: these were comfort, relaxation and privacy. The inn’s luxurious rooms were valued at between £10 and £20 each, more than many people’s entire household goods. One of these rooms valued at £20 contained:

“One bed, bedstead covering and furniture, four tables, seventeen chairs, one large looking glass, twenty pictures, window curtains.”

The pictures in these rooms were perhaps oil paintings. They also incorporated the role of a parlour as there were numerous tables and chairs for dining and entertaining. (There were between six and seventeen chairs, and between one and four tables in each room). This was due to rooms having a multi-functional use that was common until the later eighteenth century.

The inventory of Thomas Cotton provides an insight into the operation of a wealthy eighteenth-century Tewkesbury inn and the gracious standard of living it afforded the inn-holder and his family. The document also suggests that there were people in the town that were aware of metropolitan tastes and were able to provide appropriate goods and services to fulfil customers’ requirements. The presence of such a large and successful inn, which fulfilled the needs of the affluent, suggests that Tewkesbury, as a provincial town and a port, had suitable connections to supply desirable fashionable goods to those with surplus money - and to allow the wealthier sections of society to live polite and genteel lifestyles.

References

- Angus Patterson, Alehouses, Taverns and Inns in Philippa Glanville and Sophie Lee, The Art of Drinking (London, Victoria and Albert Publications: 2007), p. 77.

- R.B. Pugh, A History of the County of Gloucester, Vol.8 (London, Oxford University Press: 1968), p. 124.

- B.R. Linnell, Tewkesbury Pubs (Cheltenham, Theoc Press: 1996).

- Angela McShane Jones, ‘Clubs, Dens and Political Drinking,’ in Glanville and Lee, (eds.) (2007) p. 87.

- Bill Rennison and Cameron Talbot, Tewkesbury Wills and Inventories, 1601-1700 (Tewkesbury Historical Society, 1996).

- Located in Gloucestershire Record Office.

- Norah Day, They Used to Live in Tewkesbury (Stroud, Alan Sutton Publishing: 1991), p. 192.

- David Lloyd, The Concise History of Ludlow (Ludlow, Merlin Unwin Books:1999), p. 87.

- Anthea Jones, Tewkesbury (Guildford, Philimore: 1987), p. 93.

- Linnell suggests the Star and Garter may have been so named from 1715. (Editor)

- It was known as the Crown Inn from c 1540; then the New Inn and by 1796 the Hop Pole (Editor from Linnell).

- Linnell claims that the frontage was c1730, English Heritage classifies the Swan as “18th century” and it is first mentioned in the Woodard Database in 1779. In 1783 it merged with the White Hart next door.

- Jones, above (1987), p. 93.

- McShane Jones, in Glanville and Lee (eds.), (2007), p. 86.

- These pastimes are recorded in some other inn-holders’ inventories: for example, the inventory of Rice Prickett, a Ludlow inn-holder, exhibited 27.1.1729.

- An example of an inn that advertised this entertainment was The Eagle and Child in 1731. Lloyd (1999), p. 121.

- McShane Jones in Glanville and Lee, (eds.) (2007), p. 86.

- B.R. Linnell, Tewkesbury Pubs (Cheltenham, Theoc Press: 1996), 28.

- Inventory of Samuel Jefferies, a Tewkesbury goldsmith, proved 28.6.1733.

- A pint is approximately half a litre and a ‘quart’ of a gallon, one litre.

- Taken from Jan Read and Maite Manjon, The Great British Breakfast (London, Michael Joseph: 1981), p. 49.

- Mark Overton, Jane Whittle, Darron Dean and Andrew Hann, Production and Consumption in English Households, 1600-1750 (Abington, Routledge: 2004), p. 175.

- Lorna Weatherill, Consumer Behaviour and Material Culture in Britain 1660-1760 (London and New York, Routledge: 1988), p. 152-3.

- Helen Clifford, ‘Knives, Forks and Spoons, 1600-1830’, in Philippa Glanville and Hilary Young, Elegant Eating, Four Hundred Years of Dining in Style (London, Victoria and Albert Publications: 2002), p. 54.

Comments