Romanesque Sculpture in the Abbey

Reproduced from the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society Transactions, Volume XCVIII, 1980

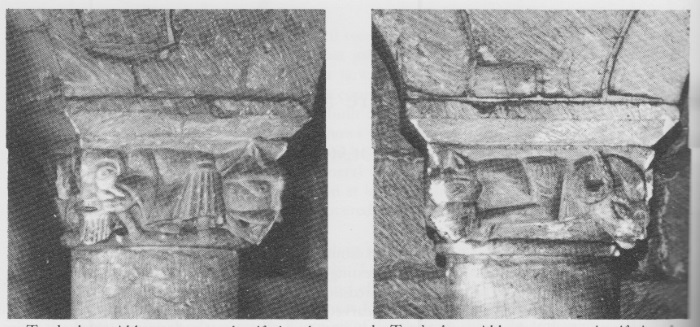

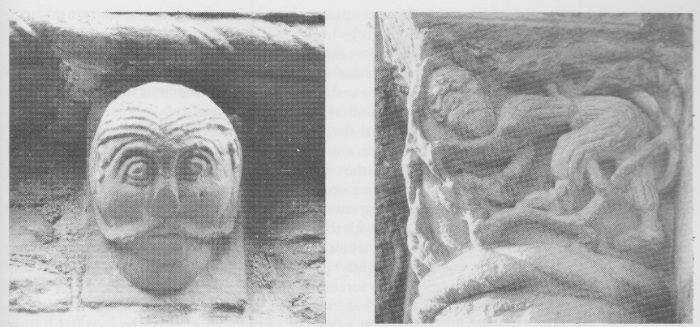

Although the Abbey Church of Tewkesbury has been much studied by historians of English Romanesque architecture, the interesting carved capitals towards the west end of the north and south triforia of the nave have passed unnoticed[1]. In the south triforium just the west capital of bay l, counting from the west, is carved. The north, east and west faces are adorned with grooves which splay towards neatly executed angle volutes. In the north triforium three capitals received more elaborate sculpture. The east capital of bay I has half of the east and north faces scalloped towards the north-east angle. The south-east angle is carved with a grotesque mask. On the south face a male figure, dressed in three-quarter length ribbed trousers, bends forward (PLATE IVa). His bearded head is set at the south-west angle of the capital and he holds the left side of his long drooping moustache with his left hand. The west face and west half of the north side are carved with a trefoil tailed, serpentine creature who appears to be about to bite the cap-like hair of the angle head. (PLATE IVc).

The east capital of bay 2 has its north face scalloped while on the west side is carved a quadruped whose grotesque head is set at the south-west angle devouring a human head. The angle head is shared with the biped on the south face of the capital (PLATE IVb). A ram's head is placed at the south-cast angle, and on the east face there is simple splayed grooving.

The west capital of bay 5 has a scalloped north face. The south and west faces are grooved towards an angle volute. The east face is similarly grooved and at the south-east angle is carved a head with rope-like moustache, almond-shaped eves, and a cleft chin.

The volute capital with the splayed grooved faces in the south triforium, bay I is clearly related to two capitals preserved in the corridor to the Vicars' Cloister at Hereford cathedral Which probably came from the choir of that building.[2] Other capitals from the Hereford choir display distinct affinities with the Herefordshire School of Sculpture, and it is to that school that we must now turn to find parallels for the remaining Tewkesbury capitals.[3]

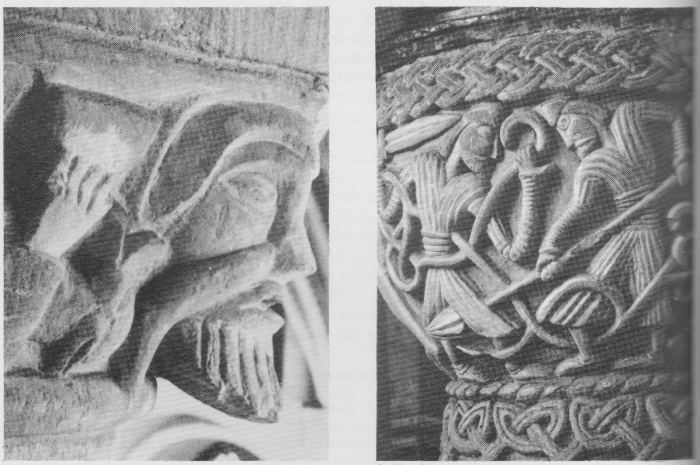

Plate V b: Leominster priory west door, left central capital

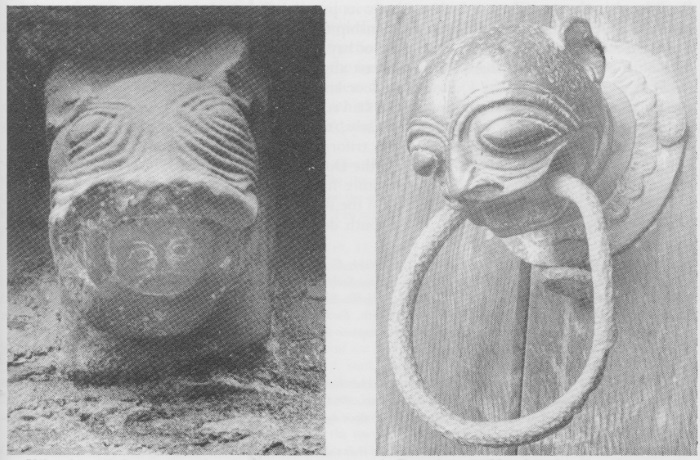

Finally in connection with this Tewkesbury figure we may compare the angle head with the one on the central right capital of the chancel arch at Rock (Worcs.).[7] Clearly they belong to the same family, and although the Rock head is not actually attached to a body its proximity to the beast on the main face of the capital is akin to the head and body relationship of the Tewkesbury figure. This placement is also used at Tewkesbury on the east capital of bay 2 of the north triforium where the bodies on the south and west faces share the south-west angle head (PLATE IV b). The form of this head reads as a cross breed of the Dormington door knocker (PLATE Vd), and one of the corbels on the north wall of the nave at Kilpeck (PLATE V c).[8] Even the diet of the human head may be paralleled in this Kilpeck sculpture. Similarly, the head at the south-east angle of the east capital of bay I in the Tewkesbury north triforium belongs to this family, the form of the mouth and teeth being particularly close to the Dormington door knocker (PLATES IV a, V d). The fact that the eyes of this Tewkesbury creature have drilled pupils does not detract from the parallel for we have seen this detail on one of the west wall corbels at Kilpeck (PLATE Va), and it is used throughout the first order of the south door of that church.9 The jambs of this door provide a comparison for the serpentine creature on the west face of the same Tewkesbury capital, while the trefoil termination to the body at Tewkesbury may be compared with the quadruped on the south-west panel of the west wall at Kilpeck. The parallel between these creatures may be taken further for both are placed immediately to the side of a head, human at Tewkesbury and a crocodile's at Kilpeck.

Plate IV d. Eardisley (Herefs.): carving on the font

The bearded figure wearing ribbed, three-quarter length trousers which splay out towards the cuff is closely related to a number of figures in the Herefordshire School. The trousers are of the same type as those worn by Samson on the Stretton Sugwas tympanum, St George on the Brinsop tympanum, and the two warriors on the Eardisley font (PLATE IV a,d).[4] These Eardisley figures are particularly close to Tewkesbury. The form of the head, the large bulbous eves and cap-like growth of the hair are common to all three figures, while the long drooping moustache of the Tewkesbury figure is like that on the right Eardisley warrior and his striated beard akin to that of the left figure on the font (PLATE IV a,c-d). Indeed the comparisons are so close that one is tempted to suggest that the same hand was responsible for both works. Zarnecki has attributed the Eardisley font to a sculptor he designates the 'Chief-Master' of the Herefordshire School.[5] This master is best known for his work at Kilpeck. The general shape of the Tewkesbury head may be compared with the figures on the left jamb shaft of the Kilpeck south door.[6] More specifically, one of the corbels on the west wall at Kilpeck shares 'With the Tewkesbury head the long moustache, slightly parted lips, striated beard, the cap-like hair groomed to a low peak in the middle of the forehead, and large, bulging eyes (PLATES I Vat Va). The general pose of the Tewkesbury figure is related to the right reaper on the left central capital of Leominster priory west door (PLATES IVa,Vb).

Plate V d. Dormington, door knocker

The Tewkesbury sculpture may therefore be regarded as a product of the Herefordshire School. The period of execution of the capitals must now be examined. Tewkesbury Abbey was founded by Robert FitzHamon in or soon after 1087[10]. In 1102 monks from Cranborne moved to the abbey, and in 1123 the church was consecrated.[11] There can be little doubt that the present building was commenced on the occasion of the foundation. Whether the change in the design of the plinth of the main nave arcade piers from square on the east side of pier 3 to round on the west represents the stage reached by the arrival of the monks in 1102 is a moot point.[12] However, in view of the simplicity of the decoration in the nave it may be suggested that the entire structure, with the exception of the elaborate upper stages of the crossing tower, was completed for the consecration in 1123. This would place the carved capitals around 1115- 23, a date which may be checked against related sculptures.

The Hereford capitals in coming from the choir of the cathedral must be dated to the earliest years of the building campaign. We know that the present structure was commenced by the time of Bishop Reynhelm, 1107-15,[13] so the capitals would have been carved before 1120, Kilpeck church was given to St Peter's, Gloucester in 1134,[14] and it seems reasonable to suppose either that the church was rebuilt immediately before this date, or that enough money was attached to the gift to permit reconstruction.[15] Leominster priory was founded from Reading abbey in 1123 and the main altar in the first bay of the nave was consecrated in 1130.[16] This would suggest that the capitals of the west door should be placed around 1135-50. The other Herefordshire School sculptures to which we have referred are not dated by any documentary evidence, but there is one more dated product of the school at Shobdon. Shobdon church was founded between 1131 and 1143.[17] In his study of the Herefordshire School Karnecki distinguished two master hands at Shobdon and Kilpeck[18]. He noted that the division of hands was clearer at Shobdon than at Kilpeck and suggested that Shobdon was the earlier work where the masters collaborated for the first time. The differences in their styles became less distinct at Kilpeck probably because each had influenced the other's work. This suggests that Shobdon should be placed in the years 1131-34. Zarnecki argued convincingly that the one master who worked in a quieter, more restrained style previously carved the tympanum of the north door at Aston (Herefordshire). He is therefore called the 'Aston .Master'. The training of the second, or 'Chief .Master' was not explained. It may now be suggested that this master received his training in Gloucestershire and that the Tewkesbury capitals are one of his earliest works. The somewhat tentative application of the sculpture to a limited number of capitals Tewkesbury is indicative of the early, experimental stages of the master's style before its full blossoming in the Herefordshire churches in the 1130s.

April 1979

References

- See A.W. Clapham, English Romanesque Architecture After the Conquest, Oxford, 1934, 34, 37, 52, 63, 100; T.S.R. Boase, English Art 1100-1216, Oxford, 1953, 92-3, G.Vebb, Architecture in Britain: The Middle Ages, Harmondsworth, 1956, 32-3; A. W. Clapham, Arch. Journal, CVI (Supplement), 1952, 10; J. Bony, Bulletin Monumental, XCVI, 1937, 281-90, 503-4. In a paper presented at the University Art Association of Canada annual meeting in February 1979 1 argued that Bony's reconstruction of a four-storey elevation in the choir and east walls of the transept was not supported by the evidence in the fabric, and instead a three-storey, barrel-vaulted arrangement was suggested. The paper is being revised for publication in Racar.

- The capitals in the corridor to the Vicars' Cloister at Hereford were removed from the fabric of the cathedral in Cottingham's restoration of 1842-9.

- The connections between the Hereford cathedral capitals and the Herefordshire School of Sculpture, which have not been generally recognised in the literature, are the subject of a forthcoming article I am preparing with Sarah Nichols. For the Herefordshire School see:- (G, Zarnecki, Regional Schools of English Sculpture in Twelfth the Century, unpublished doctoral thesis, University of London, 1951; G. Zarnecki, Later English Romanesque Sculpture, London, 1953, 9-15, 54-6; T, S.R. Boase, (1953), 78-84; L. Stone, Sculpture in Britain: The Middle Ages, Harmondsworth, 1955, 66-71; S.Jonsdottir, Art Bulletin, XXVII, 1950, 171-80; Sir N.Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Herefordshire, Harmondsworth, 1963, 24-5, 1-3, 288-9; J. Beckwith, Burlington Magazine, XCVIII, 1956, 228-35.

- For the Stretton Sugwas and Brinsop tympana see Zarnecki, (1953), ills. 31 & 32

- Zarnecki, Thesis, 1951, Section II

- Zarnecki, (1953), ill. 20

- On the connection between Rock and the Herefordshirc School see Zarnecki, (1953), 14; Sir Pevsner, The Buildings of England: Worcestershire, Harmondsworth, 1968, 46, 253,

- The connection between the Dormington door knocker and the Herefordshire School of Sculpture was pointed out by Beckwith, (1956), 235.

- Zarnccki, (1953), ill. 20. It should be noted that the font at Topsham (Devon) may also be attributed to the Tewkesbury workshop: Stone, (1955), pl. 31B. The inclusion of the leonine creature in the otherwise simple scalloped decoration of the font bowl is akin to the combination of scalloped and figurative carving on the Tewkesbury capitals. The elongated body is similar to that on the west face of the east capital if bay 2 in the Tcwkesbury north triforium, the treatment of the eyes with drilled pupils is most readily comparable ith the left eye of the male figure on the south face of the east capital of the Tewkesbury north triforium bay l. This connection between Gloucestershire and Devon is by no means unique for the crypt of St Nicholas' priory, Exeter, has squat cylindrical piers and segmental vaults like the crypt of Gloucester cathedral. The main apse of the Romanesque Exeter cathedral, which was in line with the present transept, had a polygonal exterior like the ambulatory chapels at Gloucester cathedral, and the discovery of fragments of large cylindrical capitals after the war in the nave of Exeter cathedral suggests that the structure originally had huge main arcade columns like Tewkesbury and Gloucester: Sir Pevsner, The Buildings of England: South Devon, Harmondsworth, 1952, 132.

- Dugdale, Monasticon Anglicanum, 11, 1819, 53.

- Dugdale, II, (1819), 53. The date of the consecration is variously given:- 1121 (Florence of Worcester); c.1125 (Annales de ecclesiis et regnis Anglorum); 1123 (Annules monastreii de Theokesberia). Sec Lehmann-Brockhaus, Lateinische schriftquellen zur Kunst in England, Wales and Schottlund vom Jahre 901 bis zum Jabre 1307, 2nd. Band, Munich, 1956, 560.no 4356.

- Such 'Vbreaks' in the design of piers are not necessarily indicative of a stoppage in the building campaign but may be read in connection with liturgical divisions of the church, For example, at Norwich cathedral the spiral piers of the nave arcade, numbers 3 (now recased) and 5, mark the altar area of the nave. At Castle Acre Priory the masonry, Barnack and Carstone, is confined to the liturgical choir which encroaches one bay into the nave, which Barnack stone is used alone. At Hereford cathedral the first three capitals of the arcade are carved with foliage while the remainder are plain scallops. Again perhaps liturgical division of space is here emphasised.

- Bishop Reynhelm (1107-15) is recorded as the founder of the cathedral in the Calendar of Obits. (Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, Herefordshire, I, South-West, 1931, 90.) This does not necessarily mean that Reynhelm began the construction of the present building but rather that the choir was ready for use in his time, (Journal of the British Arch. Association, XXVII, (1871), 56.) I should like to thank Richard Halsey for this reference.

- W. Dugdale, Monasticon Anglicanum, I, 1817,

- Professor Zarnecki informs me that he prefers this dating for the sculpture at Kilpeck rather than that suggested in 1953, pp. 9-10.

- W. Dugdale, Monasricon Anglicanum, IV, 1823, 51.

- The documentation is discussed by Zarnecki, (1953), 9-10.

- Zarnecki, Thesis, 1951, Section II,

Comments