Lucile Bell, 1916-2003

by John Dixon

to Expand

I first met Lucile Bell when we held meetings to set up THS in 1991. Although then I knew little of her celebrity, I was immediately impressed by her enthusiasm and, throughout the next twelve years, she was wonderfully supportive of our efforts.

I was privileged to visit her in both her homes at the Mythe and then in Turners Court; frequently we corresponded as she assisted me with research. Only recently she was trying to help me learn more about the founding of the Civic Society when she was so indignant at the threatened demolition of the Doddo Café.

On the day she was taken ill I wrote to her, enclosing a short portrait of John Moore’s contribution to the preservation of Tewkesbury’s architectural heritage when he and Lucile were proud to earn the epithet “Meds”! Sadly, that letter will never have the benefit of her advice and the Society will miss her unfailing support and the delightful aura that always accompanied her.

by D.J. Cole

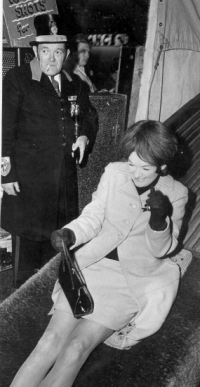

Lucile Bell, who has died aged 87, was a vivacious Australian WREN who immediately stole the heart of the Gloucestershire author, John Moore, when they met at a friend’s wedding in February, 1944.

Moore, then a Lieutenant Commander in the Fleet Air Arm and a confirmed bachelor of 37, had been asked to conduct her across London to the Savoy chapel. Those were the days leading up to the invasion of Europe that were, no doubt, charged with a not uncommon urgency for emotional commitment in the face of impending danger. He was later to admit that he made up his mind to marry Lucile during that brief journey. On All Fools’ Day the ceremony took place at Caxton Hall, witnessed by Compton Mackenzie and Eric Linklater.

The couple were soon parted. Lucile returned to her duties as a staff driver at a training establishment at Portsmouth and her husband continued his role in the planning of the invasion. John Moore was attached to Supreme Allied Headquarters, having been relieved of flying duties following a bout of rheumatic fever. He worked for the Admiralty Press Division alongside Ludovic Kennedy and Nicholas Monsarrat, having a particular responsibility for media liaison in connection with the Mulberry floating harbour and Pluto pipeline projects. He landed at Arromanches beach on D-Day+1.

Lucile Douglas Stephens was born at Melbourne on 4 June, l916, the third child of Henry Douglas Stephens, a distinguished Australian paediatrician. She was an academically gifted child and became Head Girl of St. Catherine’s School before going on to the university to read English Literature.

Much to her father’s displeasure, she abandoned her studies in 1937, instead seizing an opportunity to accompany a girlfriend to Europe. After six weeks at sea, the pair disembarked at Genoa and travelled extensively before reaching London. During that journey, Lucile developed a passion for European culture which determined that she would never return to live in her native land.

She settled temporarily in England to replenish her resources through secretarial work, before ignoring the gathering threat of war and setting off for the continent once more. As a seventeen-year-old girl, Lucile had gone aboard a German warship making a goodwill visit to Australia, where she met a handsome submariner - Gerhard Stamer. During the summer of 1939 she stayed with his family near Munich and they took her on an extended tour of the Rhine and Moselle. Quite by chance she met a British Consul on 26 August, who advised her immediately to leave Germany. After a series of adventures travelling overland through the chaos of France, she arrived back in Dover on the very eve of war.

Having left it far too late to heed her father’s entreaties to return to the perceived safety of the Southern Hemisphere, Lucile embraced the war effort. After a period peeling potatoes in a fire service canteen, she became a stretcher car driver and served throughout the Blitz in London’s east-end from a base at the Elephant and Castle. In 1943 she joined the WRNS.

Shortly after her marriage she fell seriously ill and was given only months to live. Her husband was allowed three months compassionate leave to be with her. The pair had little money on which to exist and, although John Moore had struggled in pre-war years to make his way as an author, she encouraged him to spend the time writing. In six weeks, he completed the book that was to make his name - Portrait of Elmbury - a pen picture of life in his home town of Tewkesbury during the first decades of the century.

Happily, Lucile made a full recovery, albeit she was unable to conceive a longed-for child and, after Moore’s discharge from the Navy at the end of the war, the pair settled into happy domesticity in a village beneath Bredon Hill. Moore enjoyed successful sequels to his book when Brensham Village and The Blue Field were published soon afterwards - and he went on to write a further fourteen works over the next two decades.

Lucile dedicated her life to supporting her husband’s work as an author, broadcaster, naturalist and newspaper columnist. She shared his love of the theatre, the natural world and literature, and, as a skilled hostess, was equally responsible for the success of the Cheltenham Literary Festival, which he founded and organised for several years. The couple entertained lavishly with Lucile’s beauty and charms enrapturing the Poets Laureate Cecil Day Lewisand Betjeman, authors H.E. Bates, Compton Mackenzie, Monsarrat, Laurie Lee and C.S. Forester. ‘Love to the adorable Lucile’, wrote Betjeman in a thank-you letter. ‘Those half-moon eyes and that springy hair haunt me.’

Gerhard Stamer also unexpectedly reappeared in her life. Initially, John Moore did not take kindly to the postcard that arrived from the prisoner of war spending his seventh year of captivity in a South Wales POW camp. Stamer, who had been shipwrecked in one of the first naval actions of the war, identified Lucile from publicity material connected with the publication of Portrait of Elmbury. It was some time before her husband allowed a civilised correspondence with a former enemy and it was not until after his death in 1967 that Lucile was able to visit Stamer and his wife in Germany.

The years following John Moore’s premature demise from cancer were difficult for Lucile. For much of his life, he had adopted a cavalier approach to matters of taxation and she was obliged to vacate their magnificent house and gardens for a tiny residence in order to meet the fiscal demands. Eventually, she found happiness and companionship in a twenty-five year second marriage to Dr. Arthur Bell, a noted academic and retired head teacher of Cheltenham Grammar School. Bell died in 1995.

Lucile Bell remained forever faithful to her first husband’s memory, never neglecting any opportunity to keep his name alive. She republished some of his early books, sustained an interest as patron of the Cheltenham Literary Festival and was the driving force behind the opening of the John Moore Countryside Museum in Tewkesbury. Six weeks before her death she signed copies of a limited edition re-issue of his first novel - Dixon’s Cubs - originally published in 1930.

She died peacefully on 6 September, following a short illness.