46 High Street

The Obliteration of the Architectural Memory of the Moore Family

to Expand

I was inspired to write this article when a photograph of 46 High Street, the office of Moore and Sons, graced the cover of a recent John Moore Society Journal. I hoped there would be an article based upon it, but I was to be disappointed. I, therefore, wrote the article.[1]

I really had hoped that the Society might be declaring its indignation at the fate of the shop, now it has been converted into a Subway Fast Food restaurant. However, there was none. Nor was there any fuss in the town when the shop was converted and its trademark ‘Tudor’ façade was removed. Memories will fade of the long neglected building and memories will fade that this building was the business HQ of the Moore enterprise and dynasty.

Did Collins add façades in the Tudor style to decrepit buildings? The answer is we do not know as photographs are not available in great abundance before the 1903 Gardner’s Guide.

However the Tewkesbury Register reported on a “Lecture on Architecture” delivered by Collins when Mayor: in this he referred to a book Old Houses of Tewkesbury: Holme Castle etc by the late H. Moore & F. Moore. He stated that the Bell Hotel was coated “50 years ago” in “rough cast plaster” then “picturesque half timber exposed, an example which had since been widely followed” in the house of Miss Rice at Tudor House.[2] David Cole agrees that Tudor House was “bricked over in the 17th century and then re-clad with timbering in 1897.”[3] This is the year after the Moore’s bought 46 High Street – were both buildings ‘restored’ at the same time? Exposing timbers is one thing – adding them to the building as a façade is quite different.

N. Pevsner and D. Verey join in the excoriating of what they call the “pseudo-timber-frame-style”. They agree that the Tudor House is “one of the most interesting [buildings] in the Town … it was a small masterpiece of architectural design and proportion.” However, in 1897, “the façade suffered the indignity of being covered with floor boards”! They are, of course, even more scathing about “the horribly restored no. 46.”[4]

to Expand

Added to this, the obituary of W.H. Watts is interesting:[5]

“It is with sincere regret that we have to record the demise of another old and valued resident of Tewkesbury ... On leaving Cheltenham, Mr. Watts worked in various parts of England and Wales, before becoming foreman to the late Thomas Collins in 1864. He eventually took charge of the joinery department for several years and finally became local works manager, from which position he retired some fourteen years ago … A man of marked ability and antiquarian tastes … he always took the keenest interest in the ancient architecture of the town, and was personally responsible, for the restoration of several of the timber fronts of the old houses.”

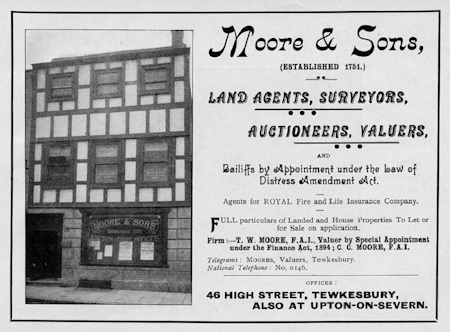

We do not know if Collins and Watts played their part in fashioning the headquarters of the Moore enterprise when the auctioneers bought the building for £400 in 1896. Gardner’s Guide was published soon afterwards, using the photograph which graced the magazine’s cover.

Unfortunately we do not have any prints by Rowe of this building before 1903. We do know, however, that from at least 1821 it was occupied by the important brewer H.A. Johns and, after his death in 1868, the building was taken over by brewer Charles Mather who, perhaps surprisingly, voted Liberal in the 1868 election. After that we can surmise that the ground floor was used for offices while the upper floors were occupied by employees: we can be sure they were grateful for such a salubrious abode.

John Moore, of course, suffered an apprenticeship in this building between 1924 and 1927 – the years of depression caused by an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease. In a Portrait of Elmbury,[6] he noted that you could still see Double Alley “by squinting sideways … It needed a coat of paint outside and a thoroughly good clean up inside. It was shabby with the shabbiness of enormous respectability.” Moore recalled that no.46 was a three-storey building, but that all the work was crowded into the ground floor. The walls were lined with books guarded since the firm’s foundation in 1750. “The dust lay thick on the firm’s old ledgers and nobody took them down off the cobwebby shelves.” This is appealing literature but Moore failed to recall that “Messrs. Moore and Son have removed offices to 46 High Street opposite Sun Street.”[7] The dust was, therefore, of thirty years’ antiquity rather than 174!

to Expand

Thomas Weaver Moore bought the premises in 1896 and censuses record that auctioneer’s clerks continued to live in the building with their families, a baby being born there in 1899. We do not know much about the interior until the 1909-13 Land Tax Survey when the inspector wrote:

“First Floor: 3 Bedrooms (Bath, Geyser, W.C.). Ground: 2 Sitting Rooms, Kitchen, Back Kitchen, Surgery (Over Kitchen & Back Kitchen), W.C.,”

All ‘mod. cons.’ pre-World War One?

John Moore wrote of his dreary experiences there in the 1920s in Portrait of Elmbury but, apart from that, we know relatively little except that the Moore firm of auctioneers petered out in the 1960s. In 1980 there was an application to the Council to alter the façade but I am not sure if it took place since my earliest memories of the declining building which housed Petite Fleur[8]seemed to be unchanged from that in the Gardner’s Guide photograph.

I had vaguely heard that the owner had been constrained to make restoration to the building – but not quite in the way in which it occurred.Dr. Sarah Lewis, the then Conservation Officer of Tewkesbury Borough Council, had the responsibility for ensuring that this building was repaired and restored and I have been very grateful for her expert help and photographs.

to Expand

Dr. Lewis writes:

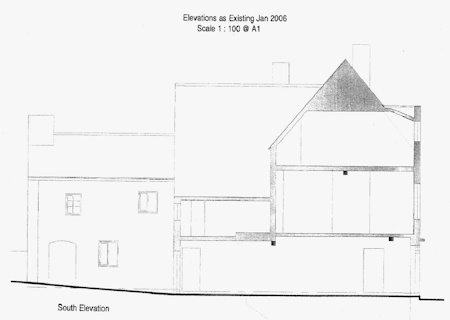

“In the course of repair it became evident that the building historically had two jettied levels and, when it was re-fronted in the C19th, they built down from the second floor jetty to the pavement thus extending the building outwards at first and ground floor levels. The construction of the replace ment front wall was a very poor timber frame incorporating a bressumer [beam] from the original building but that was all. It was clearly never meant to be seen and must always have been rendered.

The floor levels throughout the building appear to have been changed, possibly in the C17th or C18th when a brick chimney stack was erected in the middle of the building at the junction between the front and rear ranges … The timber frame was substantially altered to accommodate the new floor levels and various structural problems built into the building as floor joists were no longer notched into sturdy girding beams but into lighter weight mid-rails.

The picture is, therefore, of a three storey building first constructed in the 16th Century from timber frame with wattle and daub infill panels. Stone tiles found as packing within the panels may suggest that it had a stone-tile roof (these tiles have been found in other buildings in Tewkesbury). The building was improved in the C17th or C18th with the introduction of a brick chimney stack and hearths to heat the rooms, the floor levels were changed to create rooms of a height and form that was considered modern and attractive, so the building was perhaps owned by someone of means. It seems possible that at this time the doors, staircase and plasterwork to the ceilings were added, whether the paint scheme on the ground floor is also of this date needs to be determined, but the indications are that the owner had some pretensions to some social standing.”

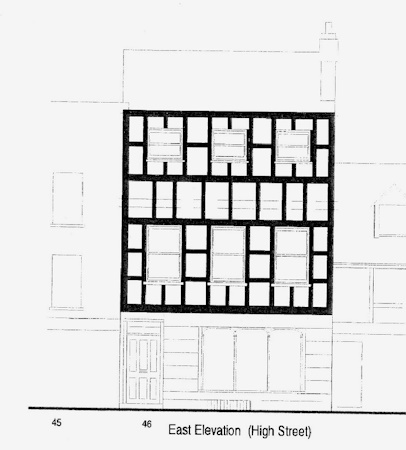

I always advise visitors to Tewkesbury to take time to study any façade. However, it is only when one is able to see the side elevation that the medieval building, which Dr. Lewis analyses, becomes apparent. In the profile the addition of the façade can be clearly seen with an older roof line lying behind.

radically changed the style of the building. Click Image

to Expand

A study of drawings for the recent renovation reveals that the agent claimed that the façade recently removed was 17th century. Dr. Lewis would refute this claim and the drawings submitted reveal an older building.

Future historians will no doubt praise its fine ‘Georgian’ proportions. However, during a long wait for a bus at the stop opposite, I was captivated by the building’s new style, which clearly shows to the discerning that the new/old front is nothing more than a façade and one wonders if the building should really look like its ‘medieval’ neighbour. The focus on this building, and on the Tudor House itself should encourage us to study further the concept of the ‘Tudor’ style of building as perpetuated by enthusiastic and generous, if possibly misguided, late Victorian architectural restorers.

References

- John Moore Society Journals: for more information visit the Society website. This article has been adapted by the author with the kind permission of the Society. https://johnmooresociety.org/

- Tewkesbury Register , 9 Mar 1893 p 1/5.

- David Cole, John Moore — True Countryman, (Malvern 2007) p7.

- David Verey, Gloucestershire 2, ‘The Vale and the Forest of Dean’ (Editor Nicholas Pevsner, 1970) p741 [has] a 17th century carved panel above its passageway. I am grateful to Tony Lord for lending me this book.

- Tewkesbury Register, 1923.

- John Moore, Portrait of Elmbury, (Windrush Press, 1995), Part 2.

- Tewkesbury Register, 25 Jul 1896, p1/1.

- Petite Fleur only occupied the building; it did not own it and was not responsible for its upkeep.

Comments