The Last Passenger Rail Service to Tewkesbury, 1961

The end of an era

“...It was time to go. Slowly, as if reluctant to leave, the train moved away from the platform. The crowds watched silently. It disappeared from view and the line looked strangely deserted. Ciné camera enthusiasts took more shots of the empty line. The crowds moved off through the dingy booking hall. A pall of silence settled over the station. An era was over...” [1]

The ‘Last Day’ of passenger service to Tewkesbury station on 12 August 1961, coming as it did during an era of great social change and modernisation, was a significantly nostalgic event – and it was recognised as such at the time. It came during the closing decade of the age of steam, the star of the show being an engine built within two years of the death of Queen Victoria. Some of the adoring public who witnessed the event were born during her reign – and many of the rest were children and teenagers, who are now approaching their retirement, their memories are a bridge to a world nearly half a century past. The event was recorded not only in the local press but on hand-held box cameras by at least four amateur cameramen.

Today, the rustic charm of Tewkesbury’s railway age is largely forgotten. However, during the July 2007 flood the embankment between Ashchurch and Tewkesbury entered into national and international consciousness as the only dry route between the town centre and the outside world – a narrow and muddy via sacré, winding between thorn bushes and blackberry thickets.

This article will concentrate on what led to the line closure and the ‘Last Day’ itself – drawing from what was reported at the time and the reminiscences of some of those who were there.

The Tewkesbury and Malvern Railway

The Tewkesbury & Malvern Line’s Station was not the first in Tewkesbury. In July 1840, an original single-line Branch of the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway opened from Ashchurch Station past the rear of what is now Morrison’s, over the area where the Baptist Church now stands, past the Maltings and eventually terminated at a station in the High Street: an extension continued to the Mill works at the Quay. [2]

The Tewkesbury and Malvern Railway Company was originally authorised through the Tewkesbury and Malvern Railway Act, 1860. An application to raise further capital was made the following year and confirmed in a second Act in the London Gazette.[3] The line, including the ‘new’ Tewkesbury Station with its temporary building, was opened on 16 May 1864 and it joined the original Birmingham and Gloucester Railway (taken over by the Midland Railway in 1846) at Ashchurch with the Worcester and Hereford Railway at Great Malvern. Stations between were Ripple, Upton-on-Severn and Malvern Wells (Hanley Road). It was fourteen miles long and the trains travelled at an average speed of 40mph with a running time of half-an-hour.

According to the Tewkesbury Register, the first train that Whit Monday consisted of 20 carriages – and ran on time! The original station in the High Street was rendered obsolete and subsequently closed down, the quay branch being used for freight and as access to a shed facility (on the town side of where the Maltings stands now). A permanent building for the new station was erected in 1872 on the southern platform, serving Malvern-bound passengers: this featured an intricate Midland Railway style glass canopy (though in later years the facing edge of this canopy was disguised by vertical wood panelling). Passengers for Ashchurch services waited in a rudimentary stone shelter – no footbridge was built and passengers crossing the line did so via a ‘boarded crossing’ at the Malvern end of the platform. A signal box was later erected a hundred yards east of the station, inside the ‘V’ where the old tracks separated for the Quay.

On 1 July 1877 the Tewkesbury and Malvern Railway Company was finally absorbed into the Midland Railway – unsurprisingly as the latter had been operating the line since the beginning. Upon the creation of the ‘Big Four’ Railway companies in 1923 the Midland became the London Midland and Scottish Railway (L.M.S.), and, of course, was Nationalised as part of British Rail in 1948.

A rural line

to Expand

The line carried a moderate level of passenger traffic, and also goods trains collecting local produce and raw goods and delivering coal and machinery. It could be of use as a diversionary route between Ashchurch and Worcester (via Great Malvern) and was once even the target of the Great Western Railway for running rights. The L.M.S. converted the line from double to single track, using the obsolete track as wagon storage, between 1922 and 1937, reputedly as an attempt to frustrate this.

Occasional snippets exist of particular users. In early spring 1915, Alice Bassett of Tewkesbury (with her daughter, Ethel) used the line to visit her husband, William, a bandsman in the 13th Battalion Gloucestershire Regiment while he was training for service on the Western Front.4 On 18 July 1923, Humphrey Household, who was at Cheltenham School, used the ‘College Boat Club Special’ from Lansdown Station to Tewkesbury, which he described as “a pleasant trip”. The following year saw the end of these specials.[5] There were also excursions, known as ‘Fishermen’s Specials’ from Birmingham to Upton via Barnt Green, Redditch and Ashchurch, which utilised a flat crossing over the main line at Ashchurch. The Second World War probably saw the greatest use of the line. The construction of underground petrol tanks near Ripple resulted in an increased use of the eastern section, while in the latter years of the War ambulance trains from Avonmouth or Southampton serviced three American military hospitals around Malvern Wells.

However, from the end of the war, passenger use started to decline. Partly, this was because of the very limited service that existed – the initial service in 1864 had consisted of just four trains each way, down to two on Sundays; by early 1951 this level of service had hardly changed. A timetable showed four Monday-Saturday eastbound services and just three full westbound services, plus three eastbound and five westbound hops between Tewkesbury and Ashchurch. Nothing ran on Sundays. It was no surprise that, given the growth in use of the motor car, especially in rural areas, passenger numbers correspondingly declined and, in 1951, the British Railways board proposed closing the line on the grounds of the high cost of maintenance. This prompted vigorous opposition, particularly from Tewkesbury Council,[6] on the grounds that the town had to be provided with a reasonable transport service, even if it was not self-supporting, and that the low revenue was caused by inconvenient time-tabling.[7]

Eventually, a compromise was reached whereby the Upton-Malvern section closed, with the last full service running on Saturday 29 November 1952. One of the factors which saved the Tewkesbury end of the railway was the anticipated inconvenience to long-distance bus travellers with luggage between the town and Ashchurch Station.[8]

A quiet decline

The result of the part-closure was a continued decline in usage – the service being further reduced. The 1955 timetable showed just two weekday eastbound services (and four on Saturdays) with just one late afternoon westbound a day (or one on Saturday morning), plus three eastbound and five westbound hops between Tewkesbury and Ashchurch. A visitor on Saturday 3 September 1955 reported that the 11.15 Ashchurch-to-Upton:

“...conveyed only children from Ashchurch to Tewkesbury and seven adults from Ripple to Upton. Returning from Upton at 1.30pm, four adults and one child were taken to Ripple, where three adults and one child joined for Tewkesbury. The train ran empty from Tewkesbury to Ashchurch...”

On 20 December 1958 another observer remarked that the only passengers between Ashchurch and Ripple were four railway enthusiasts![9] A young enthusiast, John Jennings, later recalled:“I recall [in 1961] asking the crew if any passengers were ever picked up at Ripple and the driver said that he thought that the few that had been around in the fifties must all be dead as he could not recall the last time he had seen a passenger at Ripple.” [10]

The line was a magnet for enthusiasts because of the pretty rural views from the line and the ancient Midland Railway 3F 0-6-0 Tender Engines and 0-4-4 ‘Tank Engines’ used on the line (which were supplemented by GWR ‘Pannier Tank’ steam engines from the late 1950’s). Photography in the 1950’s was becoming a cheaper hobby as a roll of eight negatives for a Brownie Box Camera was just starting to fall within the price reach of the reasonably well-off. However, those partaking in these sedate journeys had just the one carriage to enjoy!

Before we consider the line’s demise, let us read the recollections of the short hop from Tewkesbury to Ashchurch by John Sidebotham, at the time a youngster from Tewkesbury:-

“I entered the (usually empty) booking hall, and purchased my fourpenny child’s third class return ticket to Ashchurch, and then went through another door onto the platform where the train was waiting.Steam trains are either dirty, or they are romantic. It’s always one or the other: if you think they are romantic you don’t notice the dirt; and if you think they are dirty you fail to see the romance of a train journey. I must be a romantic, because I was never really aware of the dirt. For me the whole experience was a delectable assault on my senses. The locomotive was there, and even though it was stationary, it issued different sounds: the fireman shovelling coal onto the fire; the injectors whining softly; the hissing of steam; dribbles of hot water issuing fromthe cylinder drain cocks; and the smell. Oh that smell! The smell of hot oil, steam and chimney smoke must surely be one of the most evocative smells on Earth.

Getting into a compartment in the single coach train was another sensory delight. First, the clunk as the carriage door closed behind me. Then there were the wood veneers inside the compartment, often labelled ‘Crown Elm England’ or ‘Spanish Mahogany Brazil’ (that one always set me wondering, but I realise now the wood was Spanish Mahogany). There were pictures of far away places elsewhere on the railway system flanking a somewhat dirty mirror on which was inscribed in capital letters as if in code ‘BR (M)’. Lastly that wonderful dusty smell of world-weary cut moquette. If the morning was fine, I’d lower the window by pulling the large leather strap that hung down on the door, so that I could breathe in the fresh air, perfumed in spring by May blossom, and also hear the sound of the locomotive more clearly.

After a few minutes, other unseen carriage doors were slammed shut. Clunk, clunk clunk, clunk! The sound of a guard’s whistle, followed by a brief reply from the engine, and then slowly, very slowly at first, we started to move.

As we left the platform behind, you felt a regular but not unpleasant movement to and fro, back and forth, as the steam pushed the pistons ever harder and faster. As we passed the signal box at all of ten miles per hour, we crossed over onto the left hand running line and continued to accelerate until we had reached about twenty-five miles per hour. The fields and houses went by, and that wonderful engine smell came through the open window. After five minutes, we slowed down, passed under a bridge, crossed some points clickety clack, moved to the right with a screaming of flanges, and pulled into the curved platform at Ashchurch Junction…”[11]

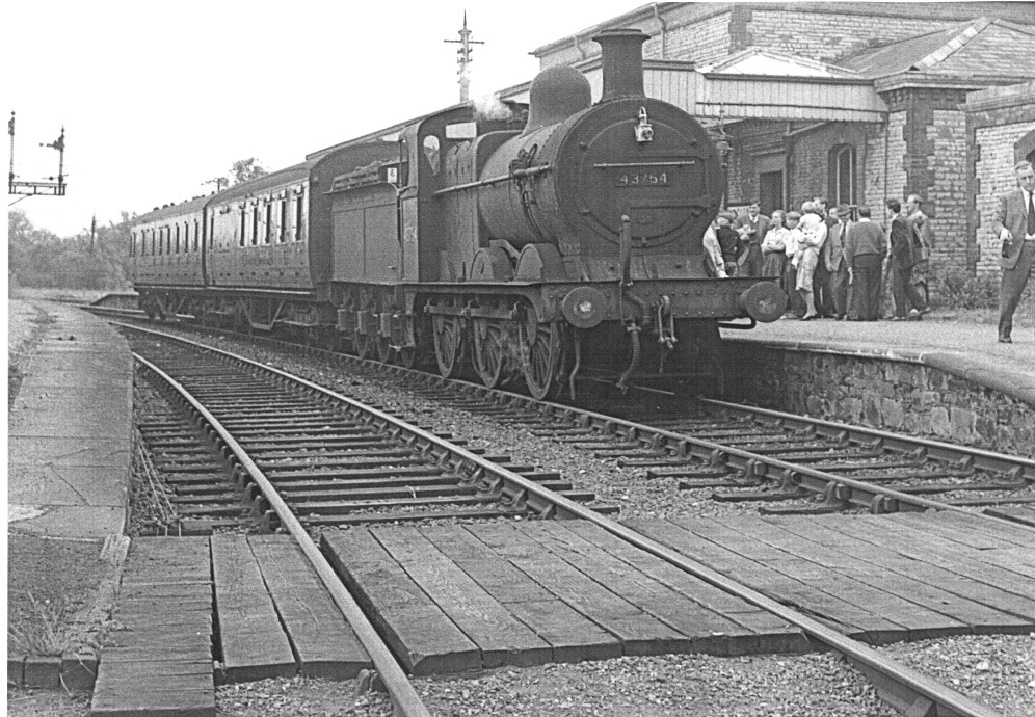

Upton-bound train on 12 August 1961.

John Jennings JJ-1172 Transport TreasuryClick Image

to Expand

However, the romance could not obscure the decline – and a major factor was the increase in road use in the fifties. In fact, part of the line between Upton and Ripple had to be diverted and a bridge built to make way for the new M50 in 1958/59; no doubt these costs were compared with the poor revenue from the line.

One must consider the political drive of the time. The 1951-64 Conservative administration was keen to expand the Motorway network, and Ernest Marples, Minister of Transport (1959-64), had himself been a major shareholder in a road-building company. Another figure of growing influence was Richard Beeching, an ICI businessman, who in 1960 was seconded by the Government to become a member of the Stedeford Committee advising on the state of British transport. Beeching developed radical ideas to close down a significant proportion of the Railway, which he saw as a relic of the Victorian age, in order to pay for modernisation – meaning the wholesale changeover to diesel technology. (Beeching later became chairman of the British Railways Board). The problem was, oddly enough, a result of the Rail network’s survival in World War II: the French and German rail systems were almost completely destroyed in 1939-45 and had to be rebuilt from scratch – both countries invested in new diesel technology. In Britain, there was no capital because of the huge war debt and, rather than invest in expensive diesel development, it carried on its steam-engine-building programme. This position had to be reassessed in 1954 with the end of fuel rationing and the corresponding rise in prosperity as the country emerged from post-war austerity. People preferred to drive to holiday destinations rather than experience dirty steam travel and delays. In the mid-fifties coal prices started to rise and oil prices fell. Consequently there arose a financial imperative for modernisation. However, there were two major funding problems: firstly that of falling revenue as the roads abstracted passengers; secondly, because of utterly different service-support systems and driving know-how needed to operate the two engine types, it was difficult to man and run steam and diesel on the same line. The Rail Modernisation Plan of 1955 was the realisation that something had to be done, and it was against this background that Beeching’s initial ideas from 1960 have to be considered. However, it must be emphasised that the closure of the Ashchurch to Upton line pre-dated the infamous ‘Beeching Report’ by two years.

Reasons for 1961 closure

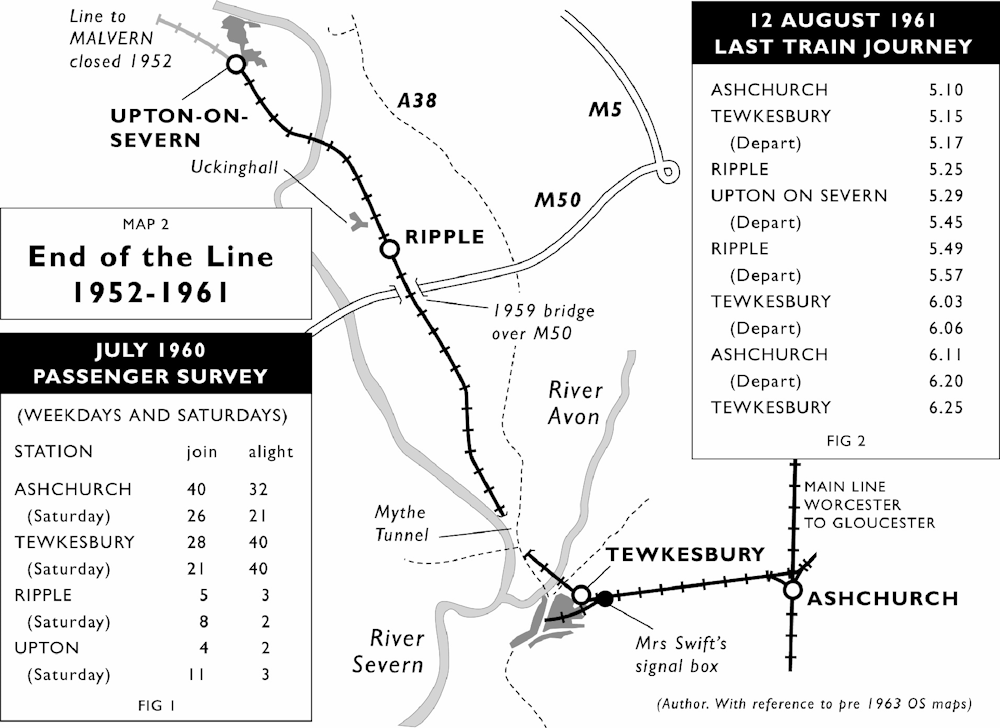

It was against this background that, in 1960, British Rail again prepared their case for closure of the Ashchurch-Upton line. A passenger survey was taken in July 1960 (see fig 1 on map 2), which starkly outlined the failure of the line to pay its way.

In November 1960 the British Rail Western Region drew up its closure proposal – they would replace the trains with road services using the Bristol Omnibus Company (nationally, this process was pejoratively referred to as ‘Bustitution’) and it was presented to the South West Transport Users’ Consultative Committee [S.W.T.U.C.C.] on 9 December.[12] Interested parties submitted written objections, including Tewkesbury Council, which selected Alderman Frank Knight to represent the council at a meeting in the Fleece Hotel, High Street, Cheltenham on Friday afternoon, 10 March 1961.[13] There were eight objectors there, representing Worcester and Gloucester County Councils, The Borough of Tewkesbury (Alderman Knight) and the Parish Councils of Ripple and Upton-on-Severn. Written objections were also supplied by the Tewkesbury Chamber of Commerce. Six men represented various British Rail bodies, Bristol Omnibus Company and the Birmingham and Midland Motor Omnibus Company. British Railways [B.R.] quickly shot down two reiterations of the 1951 objections:-

- That the timings of the trains was not convenient to the public. (B.R.’s response: “The present service has been built up in the light of many years experience” and had to fit in with connecting mainline services.)

- That branch line services should not only be judged by commercial standards but by their usefulness as a public service to remote areas and scattered communities. (Response: Services had to “pay their way” and this particular one was “grossly un-remunerative”.) Further objections and B.R.’s answers (in brackets) can be summarised as follows:-

- Possibility of replacing the steam service with cheaper new ‘diesel car’ service. (Response: Minimum cost of £5,300 p.a. for the whole route, - or £4,000 p.a.for the Ashchurch-Tewkesbury part - could not be offset by expected maximum £830 p.a. receipts.)

- Effect on life and trade in the town, the tourist trade and the fact that population growth in Mitton and Newtown would increase demand (Response: Commission observed that the latter objection had been raised in 1951 and subsequent population growth had no effect on declining passenger numbers - in fact, the Commission had noticed that Tewkesbury residents were already using omnibuses. Therefore, the line would not pay its way.)

- Inconvenience of replacement bus service between Tewkesbury and Ashchurch, to people with prams and luggage, and possible delays to transporting fish and perishables and other parcels. (Response: the omnibus service was adequate, luggage would be carried free of charge and, if it were found that there were gaps, the Commission would arrange extra omnibuses.)

- That the section between Ashchurch and Tewkesbury is well-used (Response: Replacement omnibuses would be similarly well-used, especially those replacing the popular morning and evening rail services used by schoolchildren.) [14]

There were also objections because of the fears of disruption caused to roads by flooding but these were rejected because of the perceived infrequency of flooding and that “it was the practice when such conditions arose to liaise with the police on road conditions”. Overall, the Committee found that the objections were “not well founded”, that revenue gained from the line did not warrant its use and that population growth was not likely to change this.

Alderman Knight had requested that the name of Ashchurch Station be changed to ‘Ashchurch for Tewkesbury’ and this was agreed.[15] The proposal to close the line was approved by the S.W.T.U.C.C. and this was reported in the local press.[16] The proposal was referred up to The Central Transport Consultative Committee on the 8-9 May, with the estimation that B.R. would save £10,000 immediately by closing the line, on top of the estimated £5,300 p.a. diesel running costs and an estimated £2,700 maintenance of signals, bridges etc., adding the news that “...In the Area Committee’s view no serious objections were put forward.”[17] The final blow was announced by The Transport Commission that, as from 14 August 1961, all passenger services would be withdrawn. Goods services, however, would continue to run. When the notice was read out at a meeting of the Tewkesbury Council’s Finance and Water Committee, the chairman, Alderman Knight, remarked “Three cheers for Dr. Beeching”.[18]

The last day

A poster was displayed in the station and an announcement made in the local press that the service was ending as from Monday 14 August; the last actual service would depart from Ashchurch at 6.20pm on Saturday 12August. In fact the last complete journey and the final return ‘hop’ to Tewkesbury started at Ashchurch at 5.10 p.m. (see fig 2 on map 2). A number of press reports survive of ‘The Last Day’, particularly that of the Tewkesbury Register, which is reproduced at length here, and from which the title of this article is taken. These are supplemented by the memories of the young enthusiasts who were eye-witnesses.

The Tewkesbury Register takes up the story:

“To the sound of exploding detonators and the shrilling of whistles an era which lasted 120 years came to an end on Saturday evening as the last passenger train between Ashchurch and Upton-on-Severn pulled into Tewkesbury Station... Normally the engine hauls only one carriage. Only in exceptional circumstances does it have two. This was an exceptional circumstance. It is many a long day since the platforms at the four stations have known anything like the scenes on Saturday. Crowds had swarmed on them to await the arrival of the train. The start of the last journey from Upton-on-Severn at 5.45 p.m. was delayed for at least five minutes because of the number of people wanting to board the two carriages.”

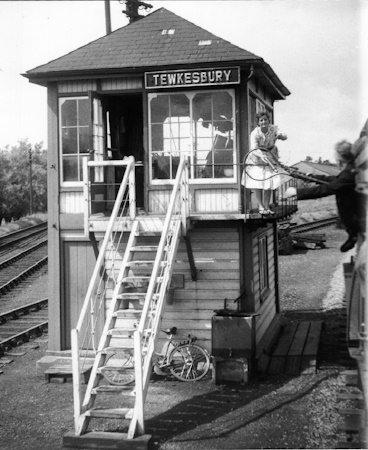

John Jennings, a train-spotter from Stratford, had already taken a journey on a mid-week day about a fortnight before the closure in the course of “my ramblings as a rather destitute student in the area”. He had scrounged a ride on the footplate of the 3F steam engine, and later been able to photograph the signalwoman as the train approached Tewkesbury.[19] This lady was Mrs. Swift, whom many local commentators remembered working in the box. The Worcester News added that she was passed a metal plaque marked ‘Malvern and Tewkesbury’ as the train passed her on its final run into Tewkesbury.[20] John Jennings had bought his return ticket, marked serial 582, ‘Return Upton to Tewkesbury’ for two shillings and sixpence [13p]. He said: “Unlike many ‘last days’ I attended in the early sixties, the closure was a sombre affair and the morning train attracted little attention, I recall that there were a fair number around later in the day.”

Everyone gets off for a look at Ripple Station.

David Aldred, holding camera on left, his friend second right. Extreme right is Mr. P Bradford, who started his rail career at Upton in 1921. (Source unknown)

David Aldred from Woodmancote and his friend Derek Blake from Bishop’s Cleeve were both thirteen. They had been dropped off for the day at Ashchurch by David’s father, with a new roll of negatives in his Brownie Box Camera. Both of them travelled on the last 5.10 return to Upton. As the train stopped at Ripple and when the engine ‘ran round’ the carriages at Upton, David and many of the other passengers alighted so as to be able to photograph and film the scene. Fifteen-year-old John Sidebotham was also there with his camera.

The Register continued:

“Small boys fought for the honour of travelling on the footplate with driver Mr. Jim Workman, of 30, Ashchurch Road, Newtown, and fireman Mr. R. Langford, who comes from Gloucester ... The train finally got under way with a passenger load it has not carried for many years. There was an enthusiastic reception at Ripple before the next stage of the sad journey to Ashchurch. Here a Register reporter mingled with the large crowds and, while he waited, spoke to some of the people on the platform. There were people like Mrs. Agnes Bishop, of 25, Fairway, Northway, who had decided to take her four small children, Vanessa, Graham, Sandra and Austin on this last trip. “Actually,” said Mrs. Bishop, “I very rarely used the train. I don’t often go into Tewkesbury. It’ll be hard, I think, on people with prams because you can’t get those on buses.” As the train pulled in there was much jostling and pushing. From every angle cameras, still and ciné, clicked and whirred. A cameraman from a B.B.C. television unit took shots of the scenes. Before the engine was uncoupled from the carriage ready to be hitched on to the other end, the Register had a chance to speak to the ‘crew’. Mr. Workman, who has been on this line for over 30 years, 18 of them as a driver, smiled to hide his obvious sadness. “Naturally I’m very disappointed,” he said, “but I’m not surprised. This has been coming for some time.” The same sentiments were expressed by Mr. Langford, perspiring from the heat of the engine boiler.”

The train returned to Ashchurch at just after ten-past-six: more crowds were waiting on the platform for the final hop back to Tewkesbury. In need of a fresh ticket, David Aldred went to the booking clerk at Ashchurch Station and asked for a ‘return to Tewkesbury’. The clerk answered: “Sorry, there’s no return service”, so he just bought the single. The Register confirmed this:

“One-way tickets only were available on Saturday and most of the passengers kept theirs as souvenirs.

One of the passengers, who left the train at Ashchurch, was Mr. P. Bradford. In a black homburg hat and neat suit he looked every inch an important executive of British Railways. He was, in fact, a relief station-master, who had travelled all the way from Nottingham to be ‘in at the death’. But, he had a very special reason for his long journey, for he started his railway career at Upton in 1921 as a porter and has a sentimental regard for this line. “Yes”, he remarked, “it’s very sad to see these lines closed down but it’s the progress of time. They have to go.”[21]

By this time the engine had been re-coupled. Everything was ready for the last stage of the journey to Tewkesbury. Cllr. Mrs. Grace Workman joined her husband on the footplate and the train moved out. The time was 6.25.”

The train had been due to pull out of Ashchurch station five minutes earlier (the station clock at Tewkesbury read 6.27 when it arrived, confirming the delay as the throng clambered aboard). The Tewkesbury Register continued:

“At Tewkesbury came, perhaps, the wildest scenes of all. There was little space to move on the platform. Again, cameras were everywhere. The train came slowly round the bend, smoke ‘pluming’ upwards. As it reached the beginning of the platform, detonators which had been placed on the lines exploded and cracked like machine-gun fire. At the same time the engine whistle screamed and one felt a queer kind of emotion. The train pulled up with the familiar grinding of the brakes.”

Waiting on the platform were cine-camera enthusiasts: Harry Butwell (who ran a jewellers in the High Street) and his wife; brothers Cecil and Wills Freeman – both pairs filmed the train as it pulled into the station; and the Freemans’ sister, the redoubtable Mary Green, in her long, striped dress and brimmed white hat, had been pacing purposefully up and down the platform before the train approached, with her handbag clasped behind her back.

59-year-old Midland 3F No. 43754

At Tewkesbury Station, at about 6.35 p.m. on 12 August 1961. The two ladies on the right have been identified as Mrs. Edith French and Mrs. Molly Day. Can anyone identify the man who dominates the photo? (David Aldred)

his cab at Tewkesbury Station (Harry Workman)Click Image

to Expand

“People crowded and pressed round the engine, trying to shake the hands of Mr. Workman and Mr. Langford. The hiss of steam from the rather old-fashioned engine was like an epitaph. A father lifted his small son on to the footplate. Mr. Workman climbed down on to the platform and posed for a photograph, looking rather bewildered by a reception he had not expected.”

The Register and the Worcester News reporters had also worked their way around the railway staff: Jim Workman was accompanied by his wife (a Town Councillor) and she remarked:

“Between my family and my husband’s there is nearly 700 years’ (sic) railway service ... I used to work on the railway myself. I was the first woman booking clerk at Tewkesbury. This is where I met my husband as a matter of fact.”.[22]

Ron Langford, the fireman, was 35 in 1961. He regretted that the“whole position of the railwayman had changed. Throughout the depression and before World War II, he said the railwayman had a secure, well paid job and a good pension at the end of his service. But loyalty to the war effort and to Government pleas for wage restraint had left him far behind in the inflationary scramble for higher pay.”[23]

Three other employees were interviewed. The guard, Joe Catlin of Northway, of five years service, just shrugged his shoulders and laughed “It doesn’t matter to me, really, I shall just go somewhere else. One train is much like another to me.” Irish-born Mr. John Dowling, of Upper Lode Locks, the leading porter at Tewkesbury, had also been on the railways five years. He said: “I’ve been dealing with passengers all that time – I shall miss it. I shall be going over to goods now.” Mr. Thomas Franklin, of 3, Hollams Road, Tewkesbury, has 26 years’ railway service behind him. For 20 years he was signalman at Tewkesbury. He is now signalman at Ashchurch. “I’m sorry to see this line go, but it had to happen of course. Trains are not just trains, you know. They’ve all got different characters.” [24]

Eventually, the train had to reverse out of the station and depart to Tewkesbury Shed by the Maltings. The crowds gently dispersed, some people buying never-to-be-used tickets as souvenirs; finally they had all departed into the summer evening. Harry Butwell filmed the empty line then followed his wife through the booking hall.

David Aldred and Derek Blake followed the engine to its shed. When he was eventually picked up, his father wasn’t happy because seven of the eight negatives on the camera had been expended.The fate of railways and railwaymen

Of the men, Jim Workman retired after the closure and died on 29 December 1969, aged 67. Ron Langford devoted his working life to the railways – in fact, he never married. He drove diesels until his retirement and he died, also aged 67, in August 1993.25 His brother was a signalman at Ashchurch, their father a signalman at Gloucester and great-grandfather a platelayer.

Of the young train-spotters, David Aldred grew up to be a teacher and later became Head of History at Cleeve School, from where he retired in 2003. John Jennings, throughout his life has taken many thousands of railway photographs, many of which can be seen at the Transport Treasury. From the 1980s he has visited over fifty countries in pursuit of steam engines.26 John Sidebotham emigrated to Sydney, Australia.

The Johnson 3F steam engine, ‘43754’, was also near retirement – she could be seen sitting occasionally at Barnwood sidings in Gloucester the following summer[27] and that November was withdrawn. She was later taken to Derby, where she had been built in 1902, and on 30 June 1963 she was scrapped.

The line itself continued to serve ‘small goods’ traffic until late 1964 when it was finally shut down. The main Tewkesbury Station building was partially taken over by John Keen and Co. (later Tewkesbury Saw Company).28 Eventually the company moved away and sometime in the 1960s the building was demolished. The wooden signal box was left derelict and burnt down in the same decade. The station and the line either side of it are now a heavily overgrown footpath.

As a commercial enterprise, steam died in the 1960s; of the men who worked them many followed into retirement. However, at the death, the enthusiasts bought decaying engines and stretches of line and gradually a parallel system of steam heritage lines emerged across the country – a romantic embodiment of the great Victorian age of steam. The events of 12 August 1961 also live on – though only in the films taken by those enthusiasts who were there.[29]

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank four railway experts: Rupert Chambers of Upton, Ian Boskett of Tewkesbury, Martin Smith (editor of Railway Bylines, Irwell Press, www.irwellpress.co.uk) and Barry Hoper (Transport Treasury picture library, Aberdeenshire – website www.transporttreasury.co.uk). Also David Aldred, John Jennings and John Sidebotham who were present on the day, and Brian Langford and Don Freeman, who missed it, but who were of great helpReferences

- Tewkesbury Register [T.R.] 18 August 1961.

- John Dixon, ‘Tewkesbury’s First — and Forgotten — Railway Station’, Tewkesbury Historical Society Bulletin (T.H.S.B.) No.12 (2003); Roger Carpenter, ‘The Tewkesbury Quay Branch’, British Railway Journal No. 40, Winter 1992.

- London Gazette [L.G.] 1 July 1862.

- Sam Eedle, ‘From the Town Hall to the Boar’s Head’ - Interview with Ethel Burford, 2001, T.H.S.B 11, (2002).

- Humphrey Household, Gloucestershire Railways in the Twenties, Alan Sutton, 1986.

- Gloucester Archives [G.A.]: TBR-A1/15.

- The National Archives [TNA] Ministry of Transport [MT] 124/197 - SWTUCC meeting 10.3.61 Min 506 app. C.

- TNA MT 124/197 - SWTUCC meeting 10.3.61 Min 506 app. D.

- 1955 & 1958 observations: ‘The Ashchurch-Great Malvern Branch in B.R. Days’ - Notes by Oswald J. Barker & Railway Bylines (Vol 9 Issue 11), Irwell Press, October 2004.

- Email to the author, Sept 2007.

- John Sidebotham ,Green and Pleasant, http://gl20.blogspot.com [dead link], 2005; with permission.

- TNA MT 124/197.

- G.A.: Tewkesbury Council minute 707, 1961.

- Objections and responses from TNA MT 124/197 - SWTUCC meeting 10.3.61 Min 506 app. C.

- above, Min 506; including App. E.

- T.R. 28 April 1961.

- TNA MT 124/197 - 8-9 May 1961.

- T.R. 14 July 1961.The author points out that, in the newspaper report, there is no recorded reaction to this comment. In view of previous events, he suggests that it was meant as an expression of irony.

- Email to the author, September 2007

- Worcester News, 14 August 1961

- One of that one the objectors at the Fleece Hotel meeting was one Councillor Bradford of Upton. The author has been unable to ascertain whether he was related to Mr. P. Bradford.

- T.R. 18 August 1961.

- Worcester News. 14 August 1961

- T.R. 18 August 1961

- Brian Langford, Ron’s nephew. Harry Workman is Jim’s brother; the railway brought the family to Tewkesbury.

- www.transporttreasury.co.uk

- Both David Aldred and John Jennings photographed her there28 (Cllr.) Ken Powell was an apprentice electrician at the time and remembers wiring it up.

- Harry Butwell - 1960’s Cine Compilation; The Jim Clemens Collection Vol. 5 ‘The Midlands Around Worcestershire’ (B&R Video Productions); Britain’s Lost Railways Vol. 2 ‘Main Lines and Branches’ (Transport Video Publishing), also that of the Freeman family, in private hands. T.H.S. also has in its collection anthologies of cine film which contain clips from this nostalgic event in the history of Tewkesbury.

Comments