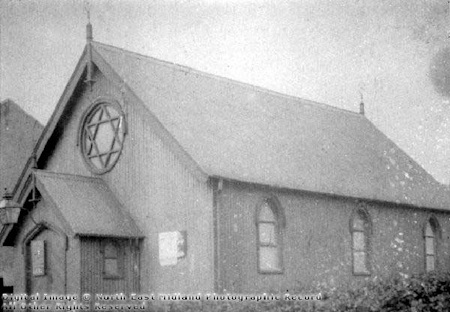

The Mission Hall, Barton Street

Our Perplexing Treasure1

with Star of David 2

This apparently disused building, now owned by the Hospital, has been the frequent subject of discussion – particularly because of the ‘Star of David’ which is incorporated into its fabric. It has never been a synagogue and was, for many years, the Mission Hall for Holy Trinity Church – it is, indeed, the adjoining building to Holy Trinity’s manse.

What, however, did surprise me was that it was, in fact, a chapel built for Primitive Methodists and that the Star of David is a religious symbol for many religions. It is the tragic experience of the Jews in Nazi Germany, which convinces us that it is uniquely a Jewish symbol.

It comprises two equilateral triangles and it is one of the oldest Christian symbols; initially representing the Creation and, later, the three equal parts of the Trinity – Father, Son and Holy Spirit. It also became an important symbol of unity in the Hebrew religion – firstly after a successful battle of King David and, subsequently, it was adopted by Zionists: Jews determined to set up a state in Palestine. When Israel was proclaimed in 1948, the Star of David was placed at the centre of the national flag. It was the Nazis who invested notoriety in the symbol.

Because ‘Zion’ means Jerusalem, which is the centre also of Christianity, it is not surprising that there is a brand of ‘Zion Methodists’, found mainly today in the USA and Africa. In fact, Primitive Methodists in Dronfield, Derbyshire, used this symbol on their ‘Tin Tab’, a corrugated iron tabernacle, which was demolished in 1959.

to Expand

Although today there is one united Methodist Church in the UK, there were rival sects until 1932. The ‘Wesleyans’ who tended to be middle class and the ‘Primitive Methodists’ who appealed to such as agricultural labourers who reacted against Wesleyan ‘respectability’ and wished to return to open air preaching by non-ordained ‘local preachers’.

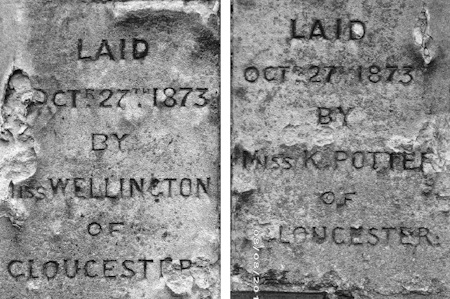

It was a Primitive Methodist Minister, Mr. Harris, who asked local builders Collins & Cullis to build them a chapel for £750 and Berrow's Journal reported the laying of foundation stones on 27 October 1873 by Misses Wellington and K. Potter from Gloucester. Both ladies proved difficult historical quarries to identify precisely, but I think that Wendy Snarey’s persistence has enabled us to identify one as the daughter of Joseph Wellington of Gloucester and the other his future daughter-in-law, Catherine Potter (who married his son Caleb in 1876).

The only problem being the “K”. Katherine Wellington spelled her name with a ‘K’ in the 1901 and 1911 censuses! She was born in Churcham, the daughter of a schoolmaster who died in 1865 followed possibly by her mother. In 1871 she was living with ‘friends’ in Kidderminster, but married Caleb James Wellington in 1876, three years after laying the foundation stone. She had two sons and died, aged 83, in 1933, living in Tuffley Avenue.

I initially thought that the Miss Wellington was her sister-in-law, Kate Welllington, who had been born in 1862 in Gloucester, daughter of Joseph a paper merchant. She went onto marry a Cornish mechanical engineer, Thomas Holman, and was living in Swansea at the time of the 1901 census. However she had died – aged only 39 – by June, possibly in childbirth.

However, Wendy challenged this verdict, as she would have been only eleven when the foundation stones were laid. She is of the opinion that it was more likely to be her older sister, Frances born c1857. She emphasised that the stone only stated “Miss Wellington” – a fact I had omitted to notice in my enthusiasm. Frances did not marry until 1886: Frances Maria Wellington married Charles George Tombs at the Register Office, Gloucester in 1886, so she would still have been “Miss Wellington”.to Expand

The New Chapel’s opening in Tewkesbury was described in Berrow’s Journal of 28 March 1874. There were three services and in the evening the congregation was so large it had to use the nearby Independent Chapel (now ‘Kingdom Hall’). The architecture was described in detail – but, significantly, there was no comment on our symbols. However the Chapel only survived eight years as, on 7 October 1882, the Tewkesbury Register reported: “We understand that the Primitive Methodist Chapel … having been offered for sale has been purchased by the Messrs. Healing and handed over to the incumbent of the Holy Trinity Church, for the various Trinity week day meetings etc. – such a building has been much needed.” The presence of Trinity was consolidated in 1887 when the widow of a former Vicar, Rev. F.J. Scott, donated ‘Beaufort House’ next door as the Vicar’s manse.

Why did the chapel have so short an independent life? The Register, no friend to Non Conformity, explained that “the efforts to get together a congregation were persisted in with a great show of energy for a year or two. Thereafter work appeared to be of a very spasmodic and unsettled kind, and the total collapse of the endeavour it was early evident was only a question of time.” It failed to point out that in 1878 the Wesleyan Methodists had opened the new and large church which still stands at the Cross. The opinion of the Register was that “a community now numbering few if any over 6000 persons, and where, besides Romanists [Catholics of the Mythe] there are four or five Nonconformist’ societies [including Baptists and Independents] striving to get and to hold congregations together.”

Trinity Hall continued to support the work of the Church in Oldbury Road. Ironically perhaps, in view of our current fascination for the symbol, a meeting was held at the chapel by the Society For Christianising Of Jews [reported in the Tewkesbury Register of 19 Aug 1893]. However, in 1932 the Vicar offered it to the Council for use by the unemployed for five days per week at nominal charge 5/- [25p] for cleaning. The Council accepted and provided free newspapers and magazines. However, the church recreation room had to be shut in March [1933] for the summer because the Town Hall grant expired and because numbers dropped. In any case men were only playing cards. The vicar noted lack of leadership and organisation and wondered also if education could be provided [Tewkesbury Register, 6 May 1933]. The end of its religious life came in 1979, when the hall was taken over by the Health Authority which today uses it as a storeroom. A humble use for a building that continues to perplex and fascinate passers-by.

References

- This is an expanded version of the article first published in the Gloucestershire Directory, October 2012 and was inspired by the great interest in the chapel shown on ‘Facebook’.

- with kind permission of Old Dronfield Society

- Taken in Barton Street by J. Dixon, 2012

- Taken in Barton Street by J. Dixon, 2012

Comments