Roman Tewkesbury

The Conquest

(Tewkesbury Museum)Click Image

to Expand

In 43ad the Roman army crossed the channel and landed in Britain bringing Britain into the historical era. This is often popularly viewed as a dramatic momentous occasion sweeping away prehistoric Britain and replacing it with a new complex Roman one. However, this view has been much discredited recently, being rightfully replaced with an interpretation of the occupation of Britain as a slow cultural change rather than any Roman Revolution.[1] Ancient Tewkesbury, like many areas, supports this interpretation.

Although the Roman forces entered Britain in 43AD, it is unknown when they would have first set foot in ancient Tewkesbury. Romanists allow the years from 43 to 47ad as the time in which the West Country was conquered. However, there is a further complication:[2] it is written by Cassius Dio that half of the Dobunni, the tribe to which Gloucestershire and some bordering counties belonged, surrendered to the Romans just after they had landed in Britain – but he does not specify which half.[3] Archaeology appears to suggest that it was, indeed, the northern half of the Dobunni that surrendered since, in the first two centuries of Roman rule, this area demonstrates a great wealth and population. Southern Gloucestershire, however, demonstrates a dearth of settlement reflective of struggle and punishment.[4] Therefore the Romans may have entered the Tewkesbury area as early as 43ad since there would have been no meaningful resistance.

This idea of Tewkesbury passing into Roman control in a peaceful manner is reflected in the settlements of the early conquest period. Late prehistoric settlements in Oldbury continue to be inhabited into the Roman era,[5] ditch systems underneath the modern town were maintained and across Walton Cardiff life continued in Iron Age round-houses.[6] Tewkesbury demonstrates a significant absence of any war cemeteries or any sudden relocation of the existing population; in fact it portrays the coming of Rome as a rather quiet occasion in Tewkesbury’s history.

Roman Tewkesbury

more decorated and thus more luxurious

than Severn Valley ware.

(Tewkesbury Museum).Click Image

to Expand

Although the arrival of the Romans in Tewkesbury may have been somewhat anticlimactic, this is not to say that they did not impact the area throughout the length of their occupation. Discoveries of Roman artefacts, across the town over the last two hundred years, demonstrate that Tewkesbury experienced a significant human settlement throughout the Roman occupation. The commonplace retrieval of Roman coins and pottery confirm this.[7] Nevertheless one must not suffer the illusion that Tewkesbury was urbanised by the Romans. Roman Archaeology for the town has mainly been supplied from the redevelopment of the Sabrina Cinema site into the Roses Theatre. Here habitation existed in timber framed, wattle and daub buildings in plots fenced off and demonstrated signs of small scale industry. They also feature storage pits and several burials respecting a track way leading out of the site.[8] This is significant because, under Roman law, it was forbidden to bury the dead within an urban area: burials had to occur outside of the city boundary whereas here they are very much part of the settlement site. Roman Tewkesbury features rural styled buildings, an absence of any administrative buildings and no ramparts or street plan: Tewkesbury was not a Roman Town. In fact, archaeology suggests that Tewkesbury remained a rural settlement with a large agricultural focus although the density of the settlement did intensify.

Furthermore a variety of pottery finds pertaining to domestic architecture were recorded. These finds complimented the arrangement of the settlement and were dominated by the distinctive Severn Valley ware which characterises the pottery record for the wider Gloucestershire area. The site also revealed Malvern grey wares, Black Burnished ware and some decorated Samian.[9]Whilst Samian ware is indicative of Roman culture with its intricate designs and motifs and would have been imported from the continent, Severn Valley ware is a local produce specific to Gloucestershire.[10] The pottery itself derives from a mixture of pre-existing native tradition and some Roman influence, giving it a much more distinctly Iron Age aesthetic. It would have been much more cheaply available than the higher class Roman decorated Samian.[11] The fact that this genre of pottery dominates rural assemblages across Gloucestershire, including Tewkesbury, suggests one of two things: either that the inhabitants of this area preferred the local indigenous traditions, or that they simply could not afford the extravagance of decorated pottery on a frequent basis.

age activity in the cross hatched areas (Author)Click Image

to Expand

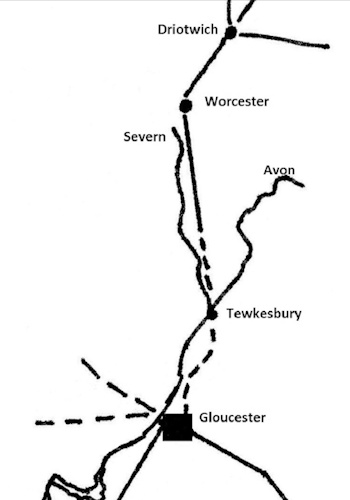

Alongside these largely rural remains there was some archaeology reflective of a higher status building. Masonry and fragments of painted wall plaster have been recovered from debris scatters but do not indicate their origin and implies the presence of at least one grander building in Roman Tewkesbury. Whilst this building may have simply been a richer estate such as a Roman villa these remains may have been from a ‘mansio’, a public inn for travellers and members of the imperial post. The rationale for this lies in the positioning of the town as it lies on, or near, the Roman road leading from the colony at Gloucester to Worcester. (The road can be followed north of Tewkesbury but its course is lost as it approaches the modern town.)

This is significant as Gloucester was a Roman colony and therefore an important urban centre for the local area; furthermore Worcester was a thriving industrial centre so traffic between the two must have been significant. In addition the road would have run through Droitwich, a major salt producing centre and there is believed to have been a land route running east from the Cotswolds that passed by Tewkesbury.[12]

This settlement was well located having access to two major waterways and a significant Roman road. This would make it a worthwhile stopping point on the Roman road system and can account for the influx of some luxury artefacts, to serve a ‘mansio’ or a trade administrator for the inhabitants. The evidence suggests, therefore, that it was, either “a large rural settlement, or a series of farmsteads”.[13]

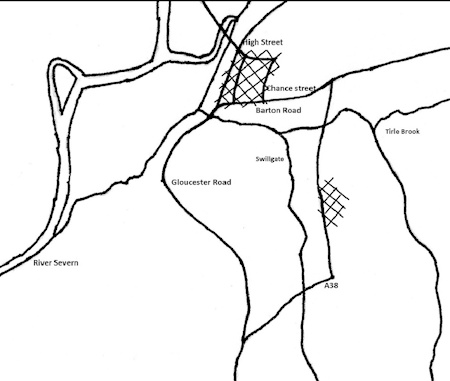

The extent of the Roman age occupation in Tewkesbury ranges from the north end of Oldbury Road, follows the High Street for its eastern perimeter before stretching westward to Chance Street. Occupation was not limited to this narrow stretch of land, nor was it consistent within it, however it does form the main nucleus of the occupation around which Roman remains have been recovered. At the north end of Oldbury, fascinating discoveries were made by antiquarians during the construction of the gasworks when an ancient well containing both human and animal skeletons was discovered as well as a collection of funeral urns.[14] The gasworks site appears to have been an area of Tewkesbury more associated with the ritual and divine during the Roman era. Around the well six or seven burials were recovered as well as at least a dozen urns from the base of the well itself suggesting that it was a cemetery of sorts.[15] Obviously a cemetery is not an unusual find in itself but the association of animal remains is. The animal bones found included the remains of a boar, two greyhounds and two ox skulls with abnormally small horns in proportion to their overall skull size.[16]

The remains placed here are striking and the act of deposition in wells as well as a focus on skulls was a peculiarly British phenomenon, thus suggesting a distinctly un-Roman character for ancient Tewkesbury. Unfortunately, since this site was dug by antiquarians, it suffers from their often undisciplined treasure seeking attitude and inexact records, with this extract regarding the well: “to the depth of eleven or twelve feet”, thus making their evidence somewhat difficult to interpret.

Nevertheless this site is clearly exceptional and would have held a significant reverential place in the local society; however its exact purpose is a mystery. Whether this burial site was for veneration of the dead or even damnation of their spirit, it demonstrates a spiritual and divine area of Tewkesbury and radiates a strikingly British influence.

The Wider Area

roads whilst dotted ones portray believed,

but unconfirmed routes. (Author)

Outside of the modern day Tewkesbury town, evidence of ancient life has been recovered on a few sites such as those unearthed at Walton Cardiff. Here a small agricultural community continued life from the late Iron Age through into the Roman era in much the same way as they always had. They lived in a ditched enclosure for farming, inhabiting a traditional Iron Age farmhouse into the early 4th century.[17] That is over 300 years of Roman occupation in which, for reasons of wealth or culture, they decided not to elaborate their house in a Romanised manner. The site did reveal some artefacts of a more Roman nature including a small amount of ‘Samian’ ware, (although again their pottery assemblage was dominated by Severn Valley products), some ‘Aucissa’ brooches (pre-‘Flavian’: 69ad) and fragments of snake bracelet.[18] Nevertheless this settlement would have benefited from the trade links that the Avon and Severn, as well as the Gloucester–Worcester Roman road, would have offered.

Recent discoveries at Bredon Hill have suggested the area possessed a more significant level of Roman influence than previously thought. These recent discoveries include a vastly important Roman coin hoard numbering just under four thousand and dating mostly to the third century. Intriguingly the coins were kept for roughly seventy years before eventually being deposited in the ground amongst the rubble of prior Roman habitation.[19] This hoard raises many questions into the nature of habitation at Bredon and in particular why they were kept for seventy years? Were they a previous hoard rediscovered? Some of these questions may never be answered but form one of many pieces coming together to demonstrate significant Roman activity upon Bredon Hill. As well as this another area of Bredon produced a selection of sixteen Roman coins, five brooches and one hair pin implying some significant presence. These remains range in date from 87ad to the mid 360s.[20] This suggests activity over a period of almost 300 years, however the nature of this activity is somewhat unknown. Local metal-detector enthusiasts and folk history claim that a group of burials exist nearby; an idea which is not too implausible when related to the finds as items of personal adornment were often buried with their owners.[21] Furthermore the insistence that there is an ancient kiln near the finds suggests the existence of a settlement, domestic or industrial, since such a structure would have been built to supply a demand. If there was a rural settlement nearby then the presence of a small cemetery would not be unusual, however pending further archaeological research this must all be noted as conjecture. For now it can only be stated that there was long-lasting Roman activity on Bredon Hill and that the area presents itself as an exciting opportunity for future archaeology.

A Romanised Settlement?

It is clear to see that Tewkesbury’s heritage goes back much further than the medieval period and the year of 1471 for which it is so famous. There was a thriving community in and around Tewkesbury throughout the Roman era; however, was this community Romanised?

The archaeology suggests the area to have been largely un-Romanised as life continued in a native manner. At Walton Cardiff the impact of Rome appears to have been minimal as they continued to live in traditional round-houses with no hint of stone buildings or mosaics in sight. This particular settlement was British in both life and death, burying their dead in the local tradition of crouched burials rather than the Roman habit of cremation.[22] In Tewkesbury, religion had a strong British influence. The inhabitants of the site of the present Roses Theatre showed some Roman influence in the manner that they abandoned round-houses in favour of rectangular structures; although the scale and the materials of their construction were akin to native rather than classical traditions. Current evidence suggests that there was only one building of a truly Roman style, although what we have left of it is only a very fragmentary unlocated scatter and also arguably is not reflective of ancient Tewkesbury but of its location in the wider Roman world. Tewkesbury was a rural settlement and like much of Roman Britain outside of the towns, it saw little Roman influence. The main impact that the Romans had on Tewkesbury was in economic terms. The Romans installed a coin centric economy in Britain, improved trade by their feverish road building, introduced greater economic opportunities and intensified the settlement through such better trade opportunities. This economic impact is archaeologically attestable through the number of Roman coins recovered from the Tewkesbury area and in the way that small quantities of Roman Samian ware appear alongside the more traditional Severn Valley ware and the Malvern ware. To believe that the Romans had no impact on Tewkesbury is obviously nonsense, but it is equally nonsensical to believe that Tewkesbury remained completely British. This was Roman Britain with a Romano-British culture; however, in this case it appears to have been a little more British than Roman.

References

- K. Branigan, ‘The New Roman Britain – A View from the West Country’, in Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeology Society [BGAS], 112, 1994, pp.9-16.

- W.H. Manning, ‘The Conquest of the West Country’, in The Roman West Country, Classical Culture and Celtic Society, ed. by K. Branigan and P.J. Fowler (London, 1976), p.17.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History 60.19, trans. by E. Cary 1924 (London: Loeb Classical Library, 1924).

- P. Salway, A History of Roman Britain (Oxford, 2001), p.14.

- A. Hannan, ‘Excavation at Tewkesbury 1972-1974’, BGAS , 111 (1993), p.24.

- J. Hart & E.R. McSloy, ‘Prehistoric and Early Historic Activity, Settlement and Burial at Walton Cardiff near Tewkesbury. Excavation at Rudgeway Lane in 2004-2005’, Iron Age and Roman-British agriculture in the North Gloucestershire Severn Vale, ed. by N. Holbrook (Cirencester, 2008).

- Hannan, p.25.

- Hannan, p.29.

- Hannan, pp.29, 43-44, 62-63.

- J. Timby, ‘Severn Valley Ware: A Reassessment’, Britannia, 21 (1880), pp.243-251.

- Timby, p.251.

- Timby, pp.39-44.

- Hannan, pp.44-45.

- M. Todd, Roman Britain 55BC – AD400 (London, 1981), p.115.

- J. Bennett, The History Of Tewkesbury (London, 1832), p.114.

- Bennett, p.115.

- Hart & McSloy, pp.12-14.

- Hart & McSloy, p.41.

- Retrieved 22 Nov 2011 from, [LINK]

- Tewkesbury Museum.

- Literal hearsay.

- Hart & McSloy, p.17.

- Salway, p.323.

- Hannan, pp.23, 39.

Comments