Coombe Hill Canal

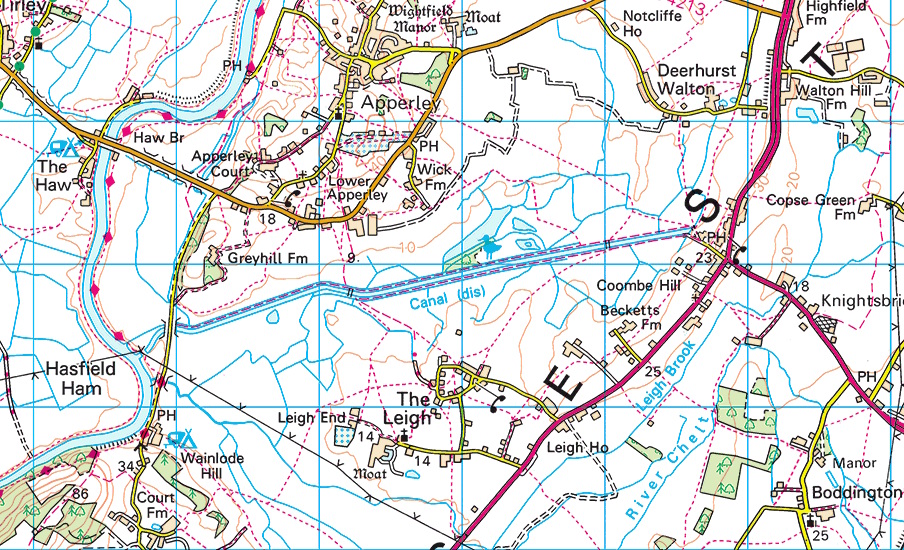

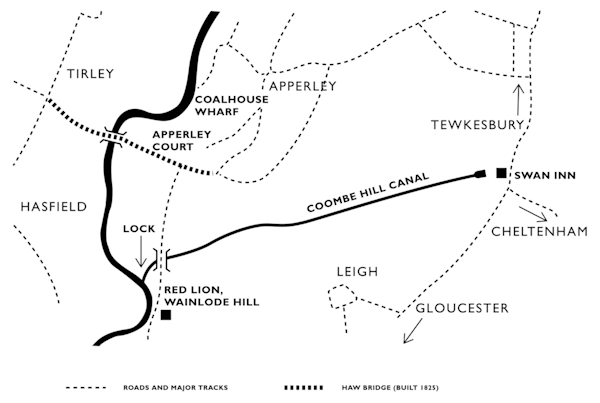

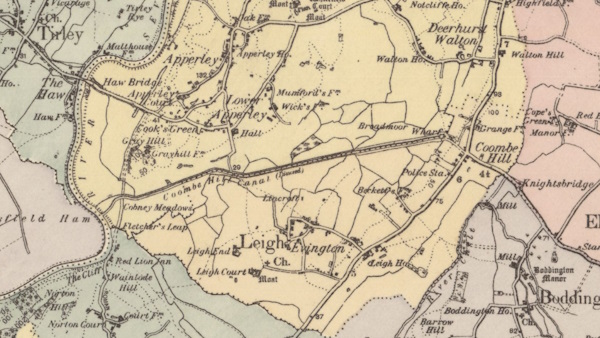

Here is a tale of a little local failure, the Coombe Hill Canal. Today, it is hidden away behind the Swan public house on the A38 between Tewkesbury and Gloucester near the junction with the road from Cheltenham. It is two and three quarter miles long from the River Severn near Wainlodes, being regularly flooded in winter but often empty in summer. Sadly, it appears that there are no photographs of the canal in operation. To understand why this canal was built – and why it failed – is to intertwine three separate stories: the rapid growth of Cheltenham, the incredible ‘boom and bust’ in canal projects during the ‘Mania’ of the early 1790s and the coming of a local tramway.

In 1700 Cheltenham was only a small village on the River Chelt, with a parish church of St. Mary and a population of around 1,500 people. With the discovery of medicinal waters in 1716, the village began to grow slowly. The catalyst for change was in the summer of 1788 when the King and his family came to stay for five weeks. So by 1800 the population had grown to 3,000 and was rising rapidly. As the local forests were cut down and not replaced, Cheltonians needed coal to keep them warm in winter, to heat the blacksmith’s forge and to provide power for the new inventions. The nearest coalfields were either in Shropshire or in the Forest of Dean. In both cases, the cost of transporting coal to Cheltenham was considerable: most accounts of opening new canals in the second half of the 18th century referred to the reduction in the price of coal brought about by the building of a new canal. The sponsors of the Coombe Hill Canal must have hoped to benefit from the growth of Cheltenham but events conspired against them from at least two separate directions.

Until the canal era began in about 1660, the rivers were the ‘motorways’ of the country; one third of all trade going up or down the River Severn while the Avon was just becoming navigable. Development of our canal network was spasmodic. Some projects failed through lack of engineering knowledge; problems of too much or too little water and unfavourable soil conditions, such as the notorious Bagshot Sands. The first phase of Canal expansion finished in 1772. Then followed a period of consolidation, a period of financial gloom after we lost the American War of Independence but, by the mid 1780s, things had improved. The Thames and Severn Canal was being built from Stroud to Lechlade with its 3,817 yard long Sapperton Tunnel being the local wonder of the age.

In the 1780’s there was a small port at Tewkesbury and a much larger port at Gloucester. To cart coal from either of these towns to Cheltenham was an expensive business so there were a series of places slightly nearer on the Severn where coal was dropped off, such as Coalhouse Wharf at Apperley and at the mouth of the River Chelt at Wainlodes. These sites would have been near the present public houses, the Red Lion at Wainlodes and the Coalhouse at Apperley (previously called the White Lion). So could a canal shorten the distance to Cheltenham?

At this time, there were no real maps to help the surveyors but it came down to two choices. The River Chelt, which was not navigable, could be turned into a canal with a series of locks; it was likely, however, that there would have been opposition from the various mill owners. Then there was the possibility of a canal from the Severn just upstream of Wainlodes Hill running for two and three quarter miles to a small basin behind the Swan public house at Coombe Hill, as the first phase of a canal to Cheltenham. This route would be about 1,000 yards shorter than using the Chelt. The only structural works would be a lock at the junction with the Severn and the canal basin, with possibly a small bridge near the lock to maintain a route along the river bank.

To start the project an Act of Parliament was required that did give permission to purchase the necessary land and obtain rights of way. In June 1792, the Coombe Hill Canal Navigation Act was passed, which was “for making and maintaining a navigable canal from the foot of Coombe Hill in the parish of Leigh in the County of Gloucestershire to join the river Severn at or near a place called Fishers, otherwise Fletchers Leap in the parish of Deerhurst”. It was claimed that the canal would save about five miles compared with the existing carriage routes. Its provisions included the right to collect water from 3,000 yards distance; water from the Chelt could be used but they could not obstruct or divert the stream of the Chelt and the canal; its associated towing path could not be more than 25 yards wide. It is important to understand the original act only covered the distance actually built: it did not allow for any further progress towards Cheltenham. The scheme did have one major weakness. The canal was planned to carry coal nearer to Cheltenham, yet little consideration seems to have been given to providing any return cargoes from Cheltenham to destinations up or down the River Severn. This would severely limit its future profitability.

There were three original owners, William Miller and Sarah Mumford, who both came from Cheltenham, together with Thomas Burgess from London. It appears Sarah Mumford was a nominee for the Miller family who had a large financial interest in the canal until 1871, although over the years they had a series of partners. The capital was £5,000 which all appears to have been spent on building the canal with another £2,000 available if necessary. Fortunately the finance for the canal was in place before the ‘Canal Mania’ reached its peak in early 1793. After that, finance for building new canals dried up for some years, with the inflation caused by the Napoleonic Wars increasing the cost of building or improving any canal considerably. According to records written much later the canal cost £5,055.15s.0d..

The canal was probably opened by February 1796 as a wide canal able to take barges of up to 70 tons, probably Severn Trows. The basin at Coombe Hill was small and probably could hold two barges at any one time. It is unclear whether men, horses or donkeys were used to haul the barges in its early days. In March 1798, the company offered a site at the Coombe Hill Wharf at a peppercorn rent to anyone wanting to build a warehouse and dwelling there. The canal was charging 2/6d. (13p) per ton, which seemed very high so there was a meeting at Cheltenham in 1801 to promote a canal to Tewkesbury. Although the project was discussed several times nothing happened. A minute book of the canal survives starting in 1802 but is not very complete. That year an advertisement had offered the canal on lease saying that the canal had done 7,000 tons of coal in 3 years. In 1808 the owners said, “It has till within the last two years been very unprofitable so as almost to be ruinous to them”.

to Expand

Stone from Leckhampton Hill was being used to build the fine houses in Cheltenham, before 1800 using inclined planes to get the stone down most of the hill. In August 1806 there was a meeting to discuss a possible tramway from Leckhampton Hill through Cheltenham and on to Gloucester docks, with a line up Gloucester Road in Cheltenham to a site which would soon become Cheltenham Gas Works. Another idea was to have a tramway to Coombe Hill. In 1807 the Swan Inn at Coombe Hill was offered for sale and part of the advertisement shows the thinking at that moment. It was nearly contiguous to the Coombe Hill Canal which communicated with the River Severn from which the said, “canal a tram or railroad is shortly intended to be made to the town of Cheltenham and if made must come within a few yards of the house”. Another idea was a canal to Cheltenham having a series of locks and a tunnel to get the canal under Coombe Hill and on to Knightsbridge. A copy of a Bill for extending the scheme is in existence. However, there was opposition from the trustees of the Cheltenham to Tewkesbury Turnpike, three of the 34 landowners and the people of Gloucester who were backing the Leckhampton to Gloucester Tramway scheme. If the Coombe Hill to Cheltenham scheme had gone ahead it is very likely that it would have suffered severe water shortages and been very unprofitable.

Coombe Hill Canal lost the battle as the tramway scheme from Leckhampton Hill to Gloucester obtained its Act of Parliament in April 1809 as the Gloucester and Cheltenham Railway. The cost of building this scheme was twice the cost predicted; yet the coal traffic target was achieved, although business was slow to develop. The aim of reducing coal prices in Cheltenham was achieved. At the Coombe Hill Coal Company yard at Chester Walk, St Georges Place, Cheltenham, coal had cost £1.15s. (£1.75p) per ton but when the tramway was in operation it was down to £1.4s. a ton and in the harsh economic conditions of 1818 Forest of Dean coal could be bought for only 16/3d. (81p) a ton. To make life even more difficult for the canal, Cheltonians preferred Forest of Dean coal to Shropshire coal.

Gloucester road at the side of the Swan Inn. A more roundabout route, but easier climb, was probably used in the early days of the canal. There seem to have been various meetings called by advertisement, where the necessary number of people to form a quorum did not attend and the meeting had to be adjourned. In September 1821 rates were lowered to a shilling a ton for coal, iron, ironstone, timber and other goods, but stone, gravel and manure were to be charged at sixpence (3p) a ton. They were also having problems with people leaving coal at either wharf without permission. Later they were charging sixpence a ton per week for goods left more than a month and some people wanted to keep parts of the yard for their own use rather than sharing it. In April 1822, the rates were reduced again from one shilling to sixpence for a while. This appears to have been raised again to 10d. (4p) a ton in September 1822 when the canal was leased to James Smith of West Bromwich with John Mabson, Edward Eagle and Thomas Clark, all of Birmingham, for seven years at £250 a year. These men were all members of the committee of the Worcester and Birmingham Canal. Then the owners of the canal raised a mortgage of £1,000 from Thomas Mortimer of Cheltenham in 1824. The following year the Worcester and Birmingham Canal were assigned the remainder of the lease to protect their interests, as it was said the Tramway Company tried to obtain control of the Coombe Hill Canal to stifle competition. In 1829 the lease on the canal was extended for a further 21 years at £500 per year.

In the 1820s, the River Severn was in poor condition and the Shropshire carriers probably had considerable problems getting their coal down the river, particularly at the shallows near Deerhurst. The first steps to improve things happened in 1831, with the Severn Commission being formed in 1842. The Coombe Hill Canal had a representative on this committee. It was only in the second half of the 19th century that things began to improve on the river: this was too late for our canal. The railway arrived in the area in 1840 and, although it was built primarily for carrying freight, passenger traffic stole the show in the early years. In the mid 1840s, coal was deposited at various station yards along the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway but it was 1848 before there was a proper rail link to Gloucester Docks. This would prove to be the death knell for the Gloucester and Cheltenham Tramway. The Worcester and Birmingham Canal also faced severe competition from the railway and thought of buying the Coombe Hill Canal and extending it to Cheltenham. The canal owners offered it for sale at £12,000. About £8,750 – provided an Extension Act was obtained and a plan was deposited – was the reply. A shareholder in the Worcester and Birmingham Canal claimed that they should not use their funds in this way; the idea seems to have been dropped.

Staffordshire and Worcester Canal Company, rather than the Worcester and Birmingham Canal Company. The lease came to an end in 1867 and tonnage on the canal had fallen to about 1,800 tons a year. G.W. Keeling, the engineer to the Gloucester and Berkeley Canal, was asked to give a report: he suggested that it should be turned into an osier bed. In 1871 it was sold to Edward Sowerby and Joseph Cockrell for £520, only one-tenth of the cost of constructing it 75 years before. It was resold in 1873 to Algernon Strickland of Apperley Court for £1,000. The Strickland family gave financial support to local causes such as almshouses, schools, village halls and local charities. Keeling looked at the canal again in 1875 and indicated that “the bridges and lock gates were in a far more ruinous condition and the Canal in a very foul state”. A summer flood had swept away the lock gates and it was not economic to repair them.

So

was passed that memorable piece of British legislation, the

Some years ago Alan Pickens bought the canal hoping to turn it into a canal centre. He did bring his narrow boat onto the canal for a while. However, this project never materialised.

In conclusion the canal is now a nature reserve and is at least safe, although it is hidden away. The short canal was built to budget, the canal basin was well built and it operated for some 80 years. It was, therefore, by no means a complete failure.

Bibliography:

- Charles Hadfield, British Canals;

- Charles Hadfield, Canals of the West Midlands;

- Steven Blake, Cheltenham

- A Pictorial History, (Phillimore, 1996);

- The River Chelt: a survey by members of Cheltenham U3A (1998);

- D.E. Bick, The Gloucester and Cheltenham Railway and Leckhampton Tramway, (Oakwood Press, 1968); Gloucestershire Records Office;

- David McDougall, Keeper of Collection at the National Waterways Museum, Gloucester;

- Janet Devereux;

- Dr. Anthea Jones, Tewkesbury (Phillimore, 2003).

Comments