Diamond Jubilee Celebrations in Tewkesbury, 1897

Celebrating the Diamond Jubilee of Victoria’s accession to the throne required months of planning, both in London, other cities of the British Empire, and in large and small communities up and down the British Isles. Celebrations in Dublin were marred by demonstrations in the evening, but in general intense patriotism was shown.

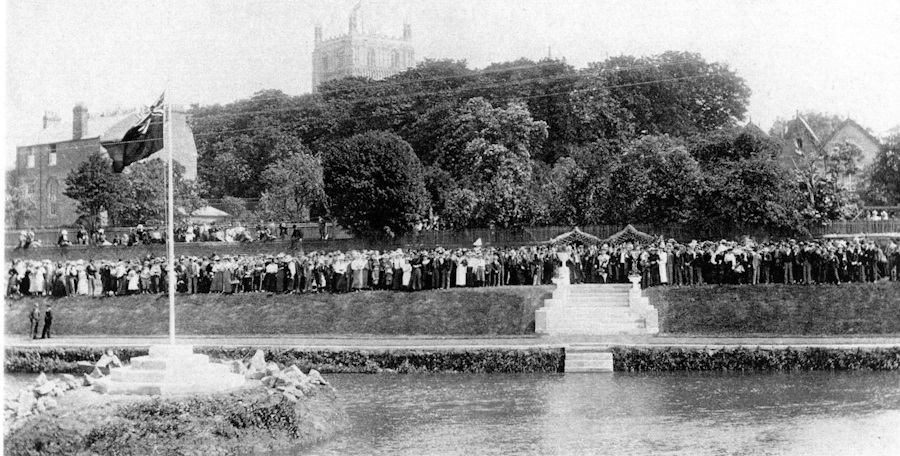

In Tewkesbury, the Town Council had organised the creation of a new public garden and pleasure park named the Victoria Pleasure Gardens, on the bank of the River Avon near the old Bowling Green and Abbey Mill. On 20 March 1897, it was reported that the Corporation would buy public wasteland between the Bowling Green and the Abbey Mill Pit. It would “raise the surface, and put seats thereon.” Mr. Gray[1] had large plans for flowerbeds, gravel paths and a fountain. The cost was estimated at between £150 and £250. The annual cost of maintenance would be about £5. In May, we are told that the Clerk to the Council was authorised to take steps to stop the old road over the site of the proposed leisure ground, the ‘Jubilee Pleasure Ground’.

There was a public ceremony on 22 June, when the ground was officially opened by the then Mayoress, Mrs. T.W. Moore. (The Mayor had previously put a notice in the paper: “The Mayor earnestly requests the Public to ABSTAIN FROM WALKING OVER THE NEW TURF at the pleasure grounds until after the opening ceremony…”).

to Expand

Prior to the big day of 22 June, special events were advertised, such as the Tewkesbury Philharmonic Society’s ‘Grand Diamond Jubilee Concert’ on 6 May. The public would hear Sir A. Sullivan’s Dramatic Cantata, ‘The Golden Legend’; reserved seats cost 3s.6d., and unreserved, 2/-. This was the age of Gilbert and Sullivan, and Edward Elgar was also becoming well known. He composed some suitably patriotic works for the Jubilee Year; fine ‘Imperial March’, and a cantata called ‘The Banner of St.George’, which centred round the Union Jack. It was also the time of his composing ‘Caractacus’, inspired by the stories of the Ancient British leader, who resisted the might of Rome; it is associated with the ancient earthworks on the Herefordshire Beacon, the highest part of the Malverns. In his book, ‘Elgar, Child of Dreams’, Jerrold Northrop Moore tells us that Elgar and his wife Alice moved to a villa at Malvern Link in June 1891. Among his compositions then were works for the Three Choirs Festival at Worcester, where his father’s music shop was still in business.

He loved walking and cycling on the Malverns and on Longdon Marsh. The advertisement for Hayward’s Ironmongery and Cycle shop in Tewkesbury High Street shows a bicycle, which may have been very much like Elgar’s own. Jerrold Moore relates that, on his deathbed in 1934, Elgar rather feebly whistled the theme from his ‘Cello Concerto’ to a friend. He said: “If ever you’re walking on the Malvern Hills and hear that, don’t be frightened, it’s only me”.Bicycles were very much a feature of life at the turn of the century. Part of the Tewkesbury celebration events was the ‘BICYCLE PROCESSION’. All those taking part were to meet at Ashchurch Railway Station and join up with other groups at the Oldfield. The route took them up to the Workhouse on the Gloucester Road at Holme Hill, where it would turn round and go back to the Cross, where they would dismiss.[2] The announcement of this in the paper said that the numbers (both sexes)who had so far promised to take part was 50. (It was a sign of the times that women were now cyclists.)

It was hoped that something could be done for the elderly and children on the great day. The Register had published a letter from the Princess of Wales, written from Marlborough House on April 29th. “In the midst of the many schemes and preparations for the commemoration of the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee, everyone comes forward with schemes for good causes…schools, hospitals, etc. One class has been overlooked, the poorest of the poor in the slums of London….Let us provide those poor beggars and outcasts with a dinner or substantial meal during the week of June 22nd.” The Princess started a fund for this with £100.

Were there many in Tewkesbury, who were poor and who lived in ‘slums’? Relative to conditions in the town at the start of Victoria’s reign in 1837, things had improved. Cholera epidemics in 1832 and 1849 had been caused by lack of clean water and overcrowded living conditions. The public health Inspectors who made a survey in 1848, reported that conditions were then as bad in Tewkesbury as in the worst slums in Birmingham. Things had improved over the years by the provision of cleaner water from the Waterworks at the Mythe (opened in 1870 and available to Tewkesbury from 1894). Dr. Anthea Jones quotes annual death rate figures in the Tewkesbury Union area (14,000 people) as having fallen from 26 per thousand in 1870 to 16 per thousand in 1878.[3] The new Hospital in the Oldbury Road, which took over the old Dispensary in 1870, under the leadership of Dr. Devereux, may have helped the drop in deaths.

However, as John Moore told readers of A Portrait of Elmbury, the old alleys, like Double Alley, which was situated opposite the Tudor House at the top of High Street, still had very bad conditions even in the early twentieth century. As we shall see, child mortality, in particular, was still high among the poorer inhabitants. Schools had to be closed at times because of epidemics of measles, for example in 1896. Rickets affected some children and diphtheria claimed many young lives.[4]

One family’s Christmas Eve in 1902 was far from happy. Kate Mary Devereux died aged 13 months, in East Street. In October 1903, little Minnie Mann, aged 2 months, died at 7 Spring Gardens. (How that name for a little child evokes her time.) Spring Gardens was one of the worst areas at that time. Later the dilapidated row of cottages was demolished and replaced with sheltered accommodation for the elderly.

So much for the context of the time; the events of the big day, 22 June, included some special things for children… a parade and special fairground rides. The town would look festive if the mayor’s appeal was heeded. “The Mayor earnestly requests the public to display as many FLAGS AND DECORATIONS as they can, from the 19th until the 23rd June”.

The Register advertised the day’s schedule. Abbey bells would ring, and there were two main processions. At 11.00 in the morning the Mayor and Corporation, preceded by the Town Band, would leave the Town Hall, followed by the Volunteers and the Fire Brigade. They proceeded to the Abbey (where there was the Victoria Jubilee Clock) for a short service, via High Street, the Oldbury, East Street and Barton Street and along Church Street.

The children had their own procession in the afternoon. They were to meet at the Cross, carrying their banners, and after singing ‘God Save the Queen’, march through the town, also headed by the Town Band, and then proceed to their respective schools for a tea party. Then there was the big treat….free fairground rides on roundabout, circular railway and swings, for two hours, in “Mr Walker’s yard near the gasworks”.[6] Walker’s were well known for the fairground equipment which they built. Everything was hand made by craftsmen.

The fun was not over. A fancy dress parade through the town was followed by a firework display at the Mythe. At 9.30 a balloon ascended, and the illuminations in the town set the scene splendidly.

The Editor had said that the “sine qua non of the day” was that it should be sunny, warm and not spoiled by rain. As it turned out, the day was dry, though cloudy at times.

Great enthusiasm had been shown. The strength of loyalty to the Crown in this area may be seen by the report that the visit of the Prince of Wales to Cheltenham in August “was greeted by splendid decorations, and that 30,000 visitors joined the inhabitants to render His Royal Highness an effective welcome, to demonstrate their affection for the Royal family”.

to Expand

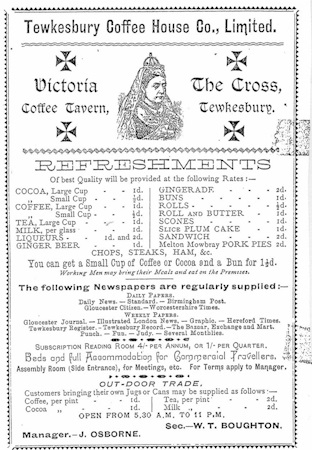

In Tewkesbury, this loyalty was, for example, to be seen in the naming of the Victoria Coffee Tavern, at the Cross in Tewkesbury. The list of refreshment prices in the advertisement included the statement: “You can get a Small Cup of Coffee or Cocoa and a bun for 1 and a half pence”. The concession was made that “Working Men may bring their meals and eat on the premises”. (Presumably they were encouraged to buy a large cup of tea to go with these, for 1d.). Newspapers were available for customers to read. Commercial travellers could stay there, and the Assembly Room could be hired for meetings.

On 29 May, the Editor wrote of the significance of the Jubilee message, which the Queen would be able to send by telegraph to all the subjects of the Empire, in so many far-flung parts of the globe. “Thank my beloved people....may God bless them”.[9] She pressed an electric button and the message went to every part. This was, of course, to be an unwelcome part of life in the First World War, when the delivery of telegrams with news of the death of loved ones on the battlefield became an all too common occurrence.

The tremendous ceremonial procession in London, when the Queen went to Westminster Abbey, was reported in the Register on 26 June. Much was made of the dignitaries from all the Imperial possessions and the selected troops in their colourful uniforms, with great patriotic crowds lining the way. The Editor’s comment on the reign included this tribute. “….The reign of a good and noble woman, who by the sheer force of beneficent influence has made so powerfully for the elevation of the British people. It is trite to say that the Queen, alike in budding girlhood, in happy wifehood, in sorrowing widowhood, has set an example which all women would do well to imitate, but it is trite only because it is true…… She is…a truly constitutional ruler.” The Register tended to write in a way which would be appreciated by the supporters of the Conservative Party.

However, it seemed that the monarchy had become generally popular again, by this time. Earlier, the Queen’s long period of mourning, for the death of her beloved husband, Albert, seemed to many to have been over-prolonged. She had retired from public life and did not carry out all the public appearances expected from the monarch, though privately she kept a good eye on things and wrote with understanding. The popularity was demonstrated that same summer by the enthusiasm for the visit of the Prince of Wales to Cheltenham, as we have seen.

29 June 2007 during the first of the

two floods of this summer (J. Dixon)Click Image

to Expand

The Queen took the Empire very much to her heart, and James Morrison’s book notes, from her private writings, that she was maternally caring for the native people .She did not like blacks to be called ‘niggers’, detesting the Boers because they were cruel to black Africans. She thought it unfair that, in the casualty lists of frontier wars, British soldiers were named, but seldom the loyal natives. She admired the Zulus, and wished they could be friends, not enemies.

That the Empire itself was still very much of public interest may be deduced from the many articles about it which appeared that year in the pages of the Tewkesbury Register. From famine and plague in India, to firm handling by “Commissioner Vorster and Mr Cronje”, of a witchdoctor’s violent persecution of a Christian girl in a village in South Africa, faraway places were brought to the attention of local residents here, because they obviously felt part of a much wider community….THE BRITISH EMPIRE.

Tewkesbury in 1897 – part of a “Land of Hope and Glory”? The issues of the Tewkesbury Register newspaper in the summer of 1897 tell how the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria’s accession to the throne was celebrated and commemorated in this area. The general events of Empire and State were topics which were thought by the Editor to be of interest and concern to local readers; a detailed account of the proceedings of the Select Committee of the House of Commons enquiring into the ‘Jameson Raid’ on Johannesburg, South Africa, was deemed to be of as much interest as reports issued by the Borough Police about criminals who had been charged in the local courts.[10] We often associate the events of 1897 with this evocative piece of music. However, this title for an account of the events of 1897 is a slight anachronism, since Edward Elgar had not yet combined his stirring melody with the words of A.C. Benson to create the famous ‘anthem’. However, the sentiments expressed in “Land of Hope and Glory” were shared by most of the general public in the closing years of the nineteenth century, especially when Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee brought tangible benefits to the town and to “those poor beggars and outcasts” who were given a free dinner.

References

- W.H. Gray, the Borough Surveyor.

- The Workhouse is now the Shephard’s Mead retirement complex.

- A. Jones, Tewkesbury, (Phillimore, 1987) p161.

- Rickets was a disease caused by deficiency in Vitamin D and caused children to develop deformed, ‘bow’ legs. Diphtheria was an even more lethal disease: it is seriously infectious and caused by bacteria that attack the membranes of the throat and releases a poison that damages the heart and the nervous system.

- For a different interpretation of life in Spring Gardens see John Dixon, Spring Gardens (THS Briefing Document 2).

- This area was near the present Mitton Garage and Handyman Centre.

- There was later a terrible fire at their town engineering works, destroyed in 1908, which was recorded on photo at the time. Mrs. Bloxham, mother of Mrs. Kathleen Hall, wrote about it in her diary when a young girl.

- This was the future King Edward VII (1901-1910).

- The Telegraph Service, which sent telegrams via Morse Code, had come to Tewkesbury in 1868, and from 1870 would have been operated by the Post Office.

- The Jameson Raid (1895-6) was very controversial: it was an attack on the Afrikaaner Republic of the Transvaal hoping to provoke a rebellion by so-called British expatriate workers. It failed and was a major reason for the outbreak of the Boer War (1899-1902).

Comments