Tewkesbury’s Stockingers, Part II

“Prosperity to the Manufactory of Tewkesbury and Plenty to the Poor”?

‘Illustrated London News’ (R. Ross)Click Image

to Expand

It is now 1860 and the old stockinger, now in his eighties and still trying to earn a crust at the hand knitting machine, walks back from the Baptist Chapel in Church Street to his cottage in one of the alleys in the High Street. He stops for a moment at the entrance to Machine Court and listens to the hum of the few machines still operating in this time of depression. Just a few short years ago the whole town would have resounded to the noise of busy machines in hundreds of homes. He passes the home of James Blount Lewis, one of the richest hosiers in the town, who has taken over the family business after the death of his father.

His two sons have gone to Nottingham to set up in the ‘factory trade’. They are sending back reports of developments in the industry, although reluctant to abandon the domestic production and the income from frame rents. Little does the father, James, realise how this industry will grow into a major one in the Midlands and still be operating more than a hundred and fifty years later.

The old man walks to Stephens Alley, opposite the home of Edward Moore, another of the masters, destined to play his part in the new ‘factory manufacture’. Perhaps Mr. Moore is reflecting on the empty lace factory in the Oldbury, considering the possibility of starting a new venture there. The old stockinger pauses at the alley entrance, to allow ‘Lampy Loo Stephens’, the town lamplighter, onto the High Street to start his round of lighting the lamps around the town, before passing into the alley to partake of a cold supper.

The mid 19th century saw the onset of a depression, which affected Tewkesbury and the local industry, bringing the stockingers to penury. One of the major factors was the development of the railway system. Tewkesbury had been by-passed, despite a great deal of local pressure. The main line from Gloucester to Birmingham had been completed in 1840, with the town only having a branch line from Ashchurch as a sop to the town. The business brought to the town by road began to diminish, as did the barge trade on the rivers.

The Tewkesbury Register, considering all the unused frames and the unemployment, commented on “conditions of the utmost penury”, and suggested that perhaps improved housing conditions might change attitudes and get the stockingers “trooping to church and chapel”. Perhaps this comment was uttered more in hope than expectation.[1]

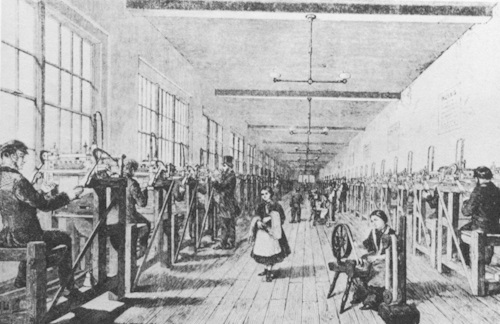

We have already noted the practice to employ children, and it must have been galling for the father to be out of work and see his wife and children earning. This became the norm, especially when the silk throwing trade became established in 1847. Humphrey Brown, the local M.P., bought the old theatre in the Oldbury to convert it for silk manufacture. The wages were low, much lower than those offered to the knitting trade, coming as it did after this trade was much declined. There can be little doubt that cheap labour was a major factor in the start of the silk industry.[2] The Register encouraged the unemployed knitters to send their children to silk throwing, to save themselves from want. It did, however, add that only “industrious” children need apply. It would seem that the trade could only survive on cheap labour, as ten years later, they were advertising for hands for a new venture but only boys, girls and some women need apply.[3]

One of the centres for the knitting trade was Jeynes Row, off the Oldbury, and the disputes which came to court came with the heading “Jeynes Row Again”, in the Register. An out-of-work knitter, accused of stealing rabbits, gave the reason that he “was out of work”, a reason that could have applied to quite a number in the town.[4] Whilst there are no clear records, it would be a reasonable estimate that about 250 knitters lived in the town; and some 50% of these would be out of work. Wages, for those in work in 1853, were of the order of 6/- (30p) to 24/- (£1.20p) for narrow frames rising to 16/- (80p) to 30/- (£1.50p) for the wide frames. As the majority of the frames in Tewkesbury were of the narrow variety, it would be reasonable to assume that the wages were somewhere around 6/- (30p) per week.[5] The Register was pessimistic about trade in the town and commented on the by-passing of Tewkesbury by the main railway line. It would appear that there were those who were more optimistic as, in 1860, moves were afoot to establish a stocking factory driven by the new ‘steam power’.[6] The application of steam did have the prerequisite of a circular or rotary motion. This change was pioneered in Nottingham (of course), with the first factory opening in 1851, but ten years later there were several factories operating there.

The Tewkesbury knitters were not over-delighted with the factory system, being used to the freedom of working at home; they would probably have found it more difficult to adjust to the discipline of factory life. The master hosiers, however, were disinclined to give up the income from frame rents: this would account for the continuation of the domestic production. The Register stated that rents were being charged at 1/1d. (6p) per week, whilst the value of frames had fallen to about 50/- (£2.50p).[7]

Although the domestic knitters preferred the independence of their home work, they would have been aware that the factory process could be a salvation. The hosiers, however, would see this as making inroads into their profits, and must have been concerned.

The first public hint of a new era in the industry was given by the Register, in its editorial of 18 August 1860: it announced that “the lace factory, shut up for so long is purchased with the adjoining property, by some spirited capitalist from London, and will soon resound to the hum of labour”. The building was, of course, the lace factory of George Freeman, in East Street, at right a angle to Trinity Walk. The purchaser was a man called Samuel Massey Crosse, and he began to enter into contracts with some of the local hosiers, one of whom was James Blount Lewis.

The new company took the name “The Patent Renewable Hosiery Company” and brought a new idea to the stocking industry. As, the stockings had the greatest wear on the toe and heel, the woman of the house would unpick the whole of the sole and re-stitch a new foot by sewing onto the stocking leg.

The main source of power came from a large beam engine situated on the ground floor, and probably provided heating for the rest of the factory. This building was of such importance as to be shown in the Illustrated London News in 1860. One of the major features was the erection of the large chimney, 125ft. high, which must have made an impression on the landscape and the citizens. The opening of the factory took place on 10 December 1860: the ultimate accolade was made by the Mayor, Councillor F.J. Prior, who was carried to the top of the chimney by winch, to top out the final bricks of the structure. For this effort, he was presented with a gold snuffbox and the first pair of stockings, at a dinner held in the Kings Head that evening, just around the corner in Barton Street! [8]

Mr. Samuel Massey Crosse was the new industrialist, and it is likely that he had discussed with local hosiers, the possibility of ‘taking in’ work from the home knitters. His Manager was Mr. L.H. Allen, who supervised all production. [9]

The stockingers must have been enthusiastic; here was a new opportunity for them away from the uncharitable master hosiers. Banners were raised in Barton Street, declaring, “Prosperity to The Manufactory of Tewkesbury and Plenty to the Poor”, and along the streets were posters with the legend, “The road to Industry leading to prosperity”.[10] Now hunger and cold would be a thing of the past, and full employment was on the way.

to Expand

Photo: Between 1861 and 1871 Thomas Holland lost both hands in an accident, but he was still able to make models, now featured in the Museum.

However, everything in the garden was not so lovely for, only a short time later, on 18 April 1861, Mr. Crosse was dead. Prior to his death, the Register reported the closure of the business of Owen and Uglow, a company having some links with Massey Crosse.[11] To the dismay of the town, the greater part of the work force was dismissed yet again, only a small number being retained to work out the remaining stocks of material. By 26 April 1861, all the remaining work force was gone, and the widow of Massey Crosse was left to deal with what remained.

It is not too difficult with hindsight, to look at the reasons for this failure. Tewkesbury was a long way away from the centres of the industry, and the owner would be out of touch with market forces. The two men, Crosse and Owen, had already fallen out with each other, when Crosse refused to manufacture the ‘Patent Renewable Stocking’! No reports are extant regarding the details of this quarrel, but even today we might not see the benefit of removing a worn out heel and sewing on a new one, when the housewife need only darn the offending heel. Further to this, Crosse had done deals with the hosiers and their hand knitters, taking in hand work and probably overstocking the factory, tying up capital in stock they could not sell.[12] It would have cost money to break these agreements with the hosiers.

After this latest blow to the local economy, some measures had to be taken to relieve the poverty of the unemployed, and a large crowd of knitters came to the Market House on the Cross, where bread to the value of 3/- (15p) was given to each knitter. The unemployed continued to suffer throughout the summer and, by the end of July, a meeting of the leading citizens was called and it was arranged that some work should be found for the neediest. The Borough Surveyor was to find work - breaking stones for the repairs to the roads. For this they would be paid up to 9/- (45p) per week.[13] There was some outcry from the ratepayers, at the increased rates (sounds familiar!) and, as a consequence, the Surveyor was to employ “only such persons who were actually in distress, and pay them in proportion to the work done”. [14]

The company was put into receivership, under a Mr. R. Walters, and this led to a sale of the seven hand frames.[15] The power frames were not in the sale and would have remained in the factory. Perhaps, like today, the receiver was looking or hoping for a buyer for a going concern.

The summer ended and a long hard winter followed, with some of the knitters finding employment through the good offices of John Garrison, editor of the Tewkesbury Weekly Record, and Cllr. J.F. Prosser, who bought frames, possibly from the receiver, and set up as hosiers, providing some work for a number of knitters. This was, of course, only a short term solution; neither of the gentlemen had any experience of knitting, but both were businessmen concerned for the welfare of the poor of the town. I am unable to find any record of how long these two gentlemen continued their good works, but it is likely that their efforts were over by the end of 1862.

Formerly, the manager’s sumptuous residenceClick Image

to Expand

In July 1861, yet another committee was raised to discuss with the receiver for the factory to be set up in production again. This time two other men were involved in these discussions – Messrs. Weaver and Prior, both J.P.s and both ex-mayors of the town. Perhaps their motives were not altogether altruistic, for there was a ready-made factory, pretty well fully equipped and with a plentiful supply of trained, cheap labour.

The major drawback, as it ever is, was the need for capital to start up the factory. In September 1862 an approach was made to Sir Cusack Roney of London; he was a director of the Dover to London Railway at the time.[16] After a visit to the town and the realisation that the rates of pay for the area were quite low, he agreed to become chairman of a new limited company, with Messrs Weaver and Prior serving on the board. A surprising appointment was that of Mr. Henry Owen, the licensee of the ‘Renewable Stocking’, a venture which had already failed. He was engaged as the general manager, perhaps because of his experience in the same industry. The Prospectus was published in the Register of 12 September 1862: a statement in this edition claimed that the company was awaiting approval “from the Inspectors of clothing for the Army and Navy”, which, if it came about, would be a major coup for the company. The same prospectus also reported that the duty on hose going into France was reduced by 65%, which could open up another market.

The requirement for capital was met initially by shares to the value of £5,000, and this sum was taken up almost immediately, but a second issue of £15,000 was not taken up. In 1864 the capital in shares only came to the value of £8,610.[17]The company began recruitment in October 1862, in order to put the factory in working order, before production began. By 21st of the month, 100 employees had been recruited, all previously unemployed. In the manner of the time, a dinner was held to mark the occasion; this time it was a little more restrained and business like. A letter had been received from the Army, Sir Cusack Roney stating that “Mr. Owen had all but convinced the Army to introduce his patent hosiery”.[18] Sadly, the Army never took up the offer and, some time later, Mr. Owen left the company, never to be heard of again, and by February of 1864, Mr. Prior had become managing director.[19]It is at this time that a new figure entered from the wings, in the person of Mr. Edward Moore, an old friend of Owen. He had already patented a type of surgical stocking, and had a patent for “improvements in dress shirts and dresses in hosiery”, and it was decided to produce under-shirts by this new design, despite the fact that as many as twenty knitters were needed to make the shirts.[20] The A.G.M. of the company took place in February 1864, reports indicating that there had been continued employment for about 130 employees, during the past fifteen months. This must have given the townsfolk confidence in the continuance of the factory system: the future was beginning to look brighter for a change.

A total of 66,600 pairs of stockings and 162 dozen of the new shirts in just over a year were, however, a comparatively low output, when compared with a hand knitter. The calculation showed the factory produced just 13 pairs of stockings per person per week, whilst a 13-year-old hand knitter even 50 years before was able to turn out 3 pairs of stockings per day, although working longer hours, but without a powered frame. Not the best comparison.[21]

The company continued to express confidence and, in fact, laid out several thousand pounds on new equipment. The chairman also indicated that there would be further purchases, amounting to some £1,000 during the coming year. The forecast was for a return of £400-£500 per annum, although one of the shareholders, John Garrison, appeared to be sceptical of the forecast, but was advised that a future dividend of 7-8% was possible.[22]

The large windows reveal its former use as a workshopClick Image

to Expand

Another false dawn broke in January 1865, when all the knitters were laid off, a situation not helped by the death of the Managing Director, Mr. Prior, in May 1866. As a result of his demise, the Official Receiver was appointed, with a new M.D., Dr. Hitch, imported to act as Manager.[24] The shareholders were unlikely to see the promised dividend, but at least the knitters – or some of them – were back at work. [25]

Optimism was ill-founded, however, as a petition to wind up the business was presented in May 1866, and an Official Liquidator was put in charge in August 1866.

Edward Moore was, however, more optimistic, stating that “all was not lost”, in a letter to the Register on 19 May 1866. He must have had an attractive business plan with which to convince the Liquidator that there was a future for the factory because, in August 1866, a private company was formed with Moore and a partner, Anthony Turner,with the title of ‘Moore and Co.’. The factory as a whole was purchased for the small sum of £1,600.[28]

This venture continued until December 1869, when the partnership was dissolved. In the following summer, Mr. Moore, having continued operating the factory, albeit with a smaller workforce, decided to retire from business and the factory and the equipment were put up for sale.[29]

So the factory era had come to an end: not with a bang but perhaps a whimper. The knitters must have recognised the end after the many ups and downs of the previous generations; they probably did so with relief, having the uncertainty of those years removed. One can only wonder at the perseverance of the investors. Several ventures had been embarked upon with financiers losing both their socks and their shirts! There is no doubt that the demise of the various owners served to increase the speed at which the several organisations failed.

The real losers, undoubtedly, were the stocking knitters of the town, having seen the demise of the hand knitting industry and then the introduction of the factory style of work, all of them having a built-in uncertainty, and none of them fulfilling their initial promise. They had suffered penury and cruelty, starvation and misery for many generations, now they would no longer have the uncertainty of the past.[30]

We are, however, left with some reminders of the past glories of the trade. The steam powered factory in East Street still exists - minus its chimney. Osborne House was the manager’s residence, whilst the workshops featured in the Illustrated London News have now been converted into cottages, called ‘North East Terrace’.[31] This is called amusingly by the locals, “Chimney Pot Row”, for obvious reasons. We can still identify Bleachers Yard, where the materials were bleached white before sale. It is the area behind the Nottingham public house and between Walls Court and Post Office Alley, upon which Humphrey Brown built his silk factory and which is now all devoted to housing. We have the several ‘nicknames’ that refer to the industry: “Tucker” Graham and “Tucker” Ryder, “Socks” Avery, “Stockinger” Linnell, and many others. They all bring to us the echoes of a not-too-distant past that helped form the character of the people who suffered and toiled at the trade.

References

- Tewkesbury Register, 5 February 1859.

- For a biography, see John Dixon, Humphrey Brown, M.P., THS Bulletin 13 (2004) pp16-20, where it is suggested that one of Brown’s motives might have been the securing of electoral popularity. The Silk Factory was until recently the home of Harvey White Engineering, but has been recently converted into flats.

- Register, 11 September 1858.

- Register: several editions, including 2 June 1859.

- worth about £14 in modern values (Editor).

- Register, 5 November 1859.

- Register, 6 October 1860.

- Author: “I wonder where the snuffbox went?”

- Register, 3 November 1860.

- Register, 15 December 1860.

- Register, 16 February1861.

- Register, 20 April 1861.

- Register, 27July 1861.

- Register, 10 August 1864.

- Register, 7 September 1861.

- Register, 12 September 1862.

- Register, 13 February 1864; worth about £400,000 in modern values (Editor).

- Register, 6 December 1862.

- Register, 13 February 1862.

- Register, 6 February 1864.

- W.B. Felkin, Account of M/c. Wrought Hosiery and Lace Manufacture, (1867), pp48-49.

- Register, 13 February 1864.

- Register, Obituary, 27 May 1866.

- For a biography, see Ian Hollingsbee, Samuel Hitch, M.D., THS Bulletin 13 (2004), pp33-35.

- Register: Letter to Editor, 27 May 1866.

- Register, 27 May 1866.

- Register, 4 August 1866.

- Gloucestershire Record Office, ref: D2079111/73. Edward Moore, a “chemist and druggist” in 1861 described himself in the 1871 census as a 43-year old “Stocking Manufacturer, Employing 11 Persons”. A local man, he is worthy of further research as he was involved in litigation locally and nationally in 1868. See the Woodard Database for more details of Wendy Snarey’s transcriptions. £1,600 worth about £74,250 in modern values (Editor).

- Register, 20 August 1870.

- Perhaps we should have a memorial to these Tewkesburians who suffered for so long, perhaps in the shape of a knitting machine sited at The Cross!

- For the specific history of this development, see Cameron Lawrence, Tewkesbury Textile Industry, THS Bulletin 2 (1993) pp7-19.

Comments