Glimpses of the Railways at Tewkesbury and Ashchurch, 1913-45

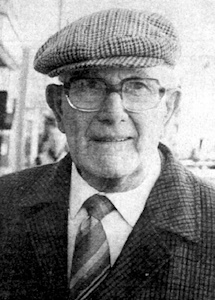

retirement in 1931[2]Click Image

to Expand

The first railway station in Tewkesbury was situated in the High Street. The law forbade steam strains to cross the High Street and use the tracks down to the Tewkesbury Quay.[3] Therefore, large horses would pull wagons of flour from Healings Mill (built on the Quay in 1865) to the Goods Yard behind the High Street Station. Railway lines crossed both the High Street and Chance Street. Eight to ten horses were employed on the job but after 1923 the horses were replaced by specially adapted tractors. A horse-drawn carrier service used to operate from Tewkesbury Station to the Swan Hotel in High Street, and also to Ashchurch. Greens ran the carriage in 1911.[4]

(Echo)Click Image

to Expand

Ernest Devereux[5] came to work at the Junction box at Ashchurch in 1937, after a career at stations such as Alvechurch and Fenny Compton. He recalled that, in the later 19th and early 20th centuries when horses were widely used in connection with the railway, there was a large provender stores at Ashchurch, which served the whole of the Midland Railway. From there food was distributed all over the route. Thousands of sacks were needed, as there were over two hundred horses at Birmingham Station alone. Hay from the verges at the side of the tracks was cut and used, as it was railway property. Ernest’s uncles, Edward (Ted) and Tom, worked at the Provender Store.

Ted sliced ropes and Tom worked on a chaff-cutting machine. Horses were considered more valuable to the railway than men.

to Expand

In the 1930s when Ernest was employed on the L.M..S. Railway, jobs were not easy to find - and could be easily lost. One guard was ‘given the sack’ because, one night, he put 1½d. [1p] belonging to the ticket office in his pocket. He forgot to hand it in the next morning. It happened because a lady travelling from Birmingham ‘Five Ways’ had not had time to purchase her 1½d. ticket before catching the train, so handed the money to the guard on her way off. This action was reported and he was dismissed instantly.

Another guard had made a habit of defrauding his employers, and was tracked down by a detective. The latter rushed onto the train at Birmingham with a bicycle, for which one paid extra. The guard entered the man’s fare into his record book, but not the 3/6d. [18p] for the cycle, which he put into his pocket, intending to spend it at the pub later.

Ernest worked at the station during the Second World War.[6] A feature of the Malvern to Ashchurch Branch Line during the war was the hospital train. This would take wounded soldiers to a hospital on the Show Ground at Malvern, a military hospital for the Americans. 55,000 casualties came straight up from the port at Southampton in specially converted trains, three days after ‘D-Day’ (6 June 1944). Many had lost their feet because they had run over mines in the ground. Prisoners of War were also transported on the railway because there was a camp at Ashchurch. At this time, there were miles of railway inside the Camp that connected with Ashchurch Station. A ‘Railway Transport Officer’ was in charge of all the tracks, sidings, etc. In those days there was an extra signal box at Aston Cross to control the comings and goings.to Expand

Road transport was also needed, and Aston Cross saw some improvements in the local roads, which were then mere lanes. German Prisoners of War, many of whom were young conscripts who were glad to be out of the war, were given this work. Ernest’s wife, Kathleen, used to give them ‘Lemon Barley Water’ to drink, as they toiled near her garden in the house next to the British Army camp that bordered on the camp perimeter, then bounded with a wire fence. On the other hand, Ernest and Kathleen had an army major billeted on them, who was an expert in guns, whose job it was to check out consignments of weapons as they came in from America, in case of sabotage. It was rumoured that it had been known for factory workers in the U.S.A. to place brass filings in the weapons to explode on the user when fired.

The German prisoners were musical: people used to come out from Tewkesbury on Sunday evenings to hear the choir of hundreds of prisoners singing as they marched back to camp. Rumour had it that various bits of ‘wheeling and dealing’ went on between prisoners and friendly locals, but as soldiers used to say: “No names, no pack drill”. Some Italian prisoners, also held at Ashchurch, made a ring out of a shilling piece for Ernest and engraved his initials on it: just an act of friendship. The Italian and German prisoners of war were kept in two separate compounds, guarded by troops with machine guns from towers on the barbed wire fences. There was a tremendous celebration on ‘V.E. Day’ (8 May 1945), when the ‘Yanks’ had a huge bonfire on the crossroads at Aston Cross, burning old, and not-so-old, tyres.

Thus Ashchurch and Tewkesbury saw their transport facilities used for far more than they might have imagined when Mr. Aldridge was first in charge at Tewkesbury Railway Station in 1911.

References

- Mrs. Irene Andrews was a member of the author’s Oral History Group at Holy Trinity Church.

- L. A. Aldridge retired in 1931 after 45 years’ service. He arrived in Tewkesbury on 17 May 1911 and stayed for 20 years. A former school teacher, he joined the railway in 1886 and was a Conservative councillor from 1921-1927. Tewkesbury Register, 31/10/1931 He died in 1943 (Woodard Database).

- For more information, see J. Dixon, ‘Tewkesbury’s First – and Forgotten – Railway Station’ in T.H.S. Bulletin 12 (2003).

- Herbert Green of 42 Oldbury Road.

- Ernest Devereux was the father-in-law of the author. Her husband David Devereux has vivid memories of Ashchurch Camp in war time.

- Ernest Devereux (1905-1991) was the Station Master at Cheltenham Lansdown Station before he retired.

![Mr. Aldridge at his<br>retirement in 1931<sup>[2]</sup>](/images/THS02460.jpg)

Comments