Tewkesbury Workhouse

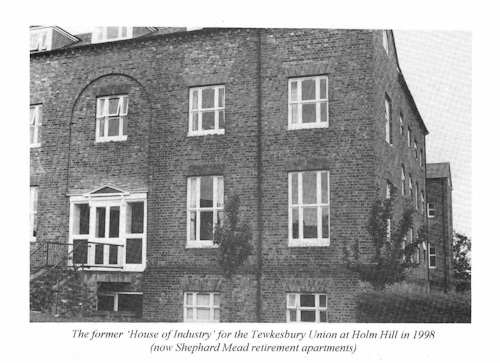

An exhibition was held in 1998 in Tewkesbury Library, which focused upon the Tewkesbury Workhouse, its successor Holm Hospital and the present residential development into which the building has been transformed. One of the visitors remarked with feeling: “They should have pulled it down!” To the suggestion that it should be kept, because it had been part of the town’s history, she replied: “But the STIGMA is still there!”

Nicholls’ ideas were included in the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834, which denied relief outside the workhouse to the able-bodied poor. The Act replaced a system first devised in 1795 by the magistrates of Speen in Berkshire, and widely copied. They had made payments to the able-bodied poor, linked to the price of bread, and the size of the family, enabling them to continue living in their own homes. The cost to ratepayers spiralled, and led to demands for change.

Our knowledge of the working of the Workhouse is assisted by a variety of sources. The Minute Books of the Board of Guardians of the Poor, which was established to administer the Workhouse after the 1834 Act, are held by the Gloucestershire Records Office. The Guardians recorded such details as punishment of minor offences and the apprenticeship of workhouse children. Summaries of the annual accounts were published in James Bennett’s Yearly Register and, later, his newspaper, the Tewkesbury Register is a good source of more ‘human interest’ stories. These include crimes committed by inmates, advertisements for tenders to supply provisions to the workhouse, and descriptions of benevolence by local people, such as Christmas entertainment. The general history of Tewkesbury records the outbreaks of cholera in 1832 and 1849, which resulted in some victims being interred in the garden behind the House of Industry. The census of 1841 and subsequent ones list the inmates there on the particular day, with ages, but not their former occupations.

An example of reporting in the early news-paper is for Christmas dinner in the Union Workhouse in 1853: “Inmates were regaled with a good substantial dinner of roast beef, plum pudding and ale, in the spacious dining hall when, with joyous hearts and eager appetites, they did ample justice to the smoking viands …” It mentions: “the superintendence of Master and Matron, Mr. and Mrs. Thompson, who were indefatigable in their efforts to render every necessary comfort … The same was greatly enlivened by the decorations of the dining hall, which was adorned with evergreens and devices appropriate to the festive season. In the front entrance was (a device) with the words ‘Thanks to our benefactors’.”

The 1841 Census lists eighteen ‘elderly persons’ aged 64-90 as resident in the workhouse; 29 adults aged 16-63 (21 women and 8 men); and no less than 63 children aged 0-15 years. The youngest was six months. Of these children, only fifteen were with their mothers. The others must have been orphaned or abandoned children. Perhaps some were a matter of ‘one child too many,’ but these were likely to be fostered out in the parish. There were seven women with children: for example, Anne Sherratt (aged 29) had five children with her. Indeed, husbands who were in prison, or who had been transported, often left dependants reliant on the workhouse. In October 1839 leave was given to Rebecca Bishop, an inmate of the work-house, to go to Worcester to see her husband, who was under sentence of transportation, before he was sent to Australia.

Workhouse children were taught to read and write which, it should be noted, was not always the case for children existing outside the workhouse. It was realised, however, that the children would be more likely to be able to support themselves when adults, if basic skills were acquired. Thus, the schoolmaster or mistress found themselves with a large class to instruct, even if some of the 63 children were too young to be taught. Eleven were aged three or younger in 1843 and this group included two-year-old twins, Emma and Sarah Moore. In the early days, the wife of the Master of the Workhouse acted as a teacher, although her skills may not have been very advanced. Discipline was sometimes needed, and rules were laid down about this. For example, a child was not to be confined in the dark, even though locking up might be used. In August 1842 two boys were guilty of ‘gross misconduct,’ and were ordered to be placed in confinement for eight hours each. It is clear that all punishments had to be noted in the official report and that those in charge were held accountable for such actions.

In 1836, the Rev. Father Hone of Tirley wrote to the Poor Law Commissioners in London, with a complaint about the way two of his parishioners, possibly children, had been treated by those responsible for Tewkesbury Workhouse. We do not know the cause of his complaint, but it elicited a reply, from no less a personage than the national Secretary, Edwin Chadwick himself. This letter proves to be a marvellous example of prose of the period: “Commissioners see no reason to doubt the Board of Guardians exercised a sound discretion in the cases referred to. The Commissioners desire further to state that they have read a copy of Mr. Hone’s letter with much regret, and lament exceedingly that a letter so intemperate in tone should have been written by a clergyman of the Church of England.”

Some early examples of the placement of workhouse children can be given from 1837. Many were of course placed as servants: Mr. Gardner of the Bell Inn took ‘a boy,’ Fred White, as a servant. Maria Mop went into service at Apperley and Charlotte Wedgwood at Deerhurst Walton. John White, however, was apprenticed to Isaac Parker. We do not know how happy a fate this was, and how far the employers took advantage of orphan children. The whim of the individual employer was all-important and there was no system of inspection. 2

Of the adult men, there was at least one blind man, John Pates, who was aged 22 in 1841. Another rejoiced in the name of Telemachus Jeynes: he is mentioned several times, first in 1835 at the age of 52 and also as troublemaker since, in April 1842, he had been fighting with the said John Pates. The Master placed them both in confinement for twelve hours. However, this did not seem to solve the problem because, in 1843, John Pates threatened to set fire to the workhouse, and was taken before the magistrates.

James Bennett, himself a Guardian for some years, was proud of the fact that the elderly could live to a ripe old age in the workhouse. In the summer of 1844 he records, “Only four deaths occurred in the workhouse, and these were old people, respective ages 78, 81, 92 and 93.” The total deaths for the year in the Parish of Tewkesbury were 136 which, with 183 in the Union parishes, give a total of 319.

However, in 1849 cholera struck for the second time in Tewkesbury. From August, when the disease broke out in Wilkes’ Alley, 940 cases of cholera/diarrhoea were reported to the Board of Health. 197 were designated cholera and 54 deaths occurred: seven of these were at the Workhouse. As in the 1832 outbreak, graves were dug in the workhouse garden, but some of the victims had to be placed in one very deep hole, together with their bedding and wearing apparel.

The care of sick paupers was another responsibility of the Poor Law Union. Tewkesbury was, however, fortunate in that inmates deemed to be insane could be despatched to the Asylum at Gloucester, as was poor Modesty Hooper in 1843. From August 1838, paupers suffering from illness were to be separated from other inmates, with the Medical Officer required to attend daily. This may, indeed, have been the start of the infirmary into which the Workhouse changed itself in 1948.

Casual visitors to the Parish were a deep concern for the Guardians but the census does not appear to distinguish between residents on the one hand and tramps and vagrants on the other. In the annual summary of paupers assisted by the parish, however, Bennett lists the vagrants separately for the period 1839-1846. Previously, they had formed part of the general listing of numbers of persons receiving ‘outdoor relief.’ In 1844, 2,822 vagrants were admitted to the casual ward during the time later known as ‘The Hungry Forties’: possibly, therefore, this was the peak of such numbers. The Guardians ruled in 1841 that vagrants were to be made to work six hours at the work-house before proceeding, so as to prevent the abuse of the system.

On arrival at the workhouse paupers were searched, washed and had their hair cropped. This was justified on health grounds, but had a humiliating effect on the individual. Uniforms were then issued to distinguish them from ordinary townspeople in a way comparable to prison inmates: early photographs show rows of identically dressed people. The children were said to have hobnailed boots which made them walk clumsily. However, children outside the workhouse might have no shoes at all. On this subject, Tewkesbury Gaol also has some interesting records: in 1821 one young woman, Susannah Matthews, who had been convicted of running a ‘disorderly house,’ was released having no shoes. One of the Bailiffs (joint Mayor) of the day, Mr. Holland, gave her a pair at his own cost.

One of the most detested aspects of the workhouse system was the separation of man and wife. There were separate, locked areas for different categories of inmates: men and women were housed in different sections, not only for sleeping, but also for food and exercise. There was some justification, however, for protecting young girls and women from proximity to disreputable or disturbed male paupers. As it was, there was said to be a corrupting influence when hardened young women mixed with girls who had been made pregnant and deserted, but were basically decent and, indeed, innocent. Young children were fed at set times, of course, and no amount of crying for food in between was of any avail, although one can imagine that some mothers might well hide a little food about their person for when the child was hungry again.

The diet at the workhouse, like everything else in the Union establishment, was supposed to be less attractive than that found in the outside world. We have the diet list for 1836. Breakfast, the same every day, was 6oz bread for men, 5oz for women, with one and a half pints of gruel. The basic recipe for this infamous dish was one tablespoon of oatmeal to every pint of water. Dinner on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, provided one and a half pints of soup with 5oz of bread. On Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays, however, Dinner yielded 5oz of meat and 1lb of potatoes. Saturday, as a contrast, produced simply boiled rice: 14oz for men and 12oz for women. There was also Supper, consisting of either 6oz of bread and 1½oz of cheese, or bread and broth. The cost of meat was 37 shillings a cwt, cheese 26 and oatmeal 20 shillings a cwt. Flour was 27 shillings a sack and rice cost 18 shillings per cwt. [3]

By comparison, we are told that the prison ration in 1842 was 292oz of solid food a week: the workhouse ration was half of that. It was indeed usually the poor quality of workhouse fare that was criticised: gruel with no milk or sugar was not popular! Many workhouses did not allow cutlery for the inmates and so gruel would be drunk from a bowl. In another area in 1860, one Poor Law Inspector went round an old people’s ward collecting teapots, which family members had given to the old folk, and then ceremonially smashed them.[4] It was, however, noted in Tewkesbury’s records that gradual improvements were allowed. From February 1836 ‘old people over 60’ were to be allowed tea, sugar and butter for breakfast instead of gruel. This must have occasioned disapproval from the authorities, though, because in September the minutes stated that the tea and butter allowance was only to be given to paupers who, from old age or sickness, “should require such indulgence.” Many work-houses were notorious for poor quality food, but Tewkesbury must have insisted on reasonable standards because complaints about the quality of flour supplied by those who had the contract for the workhouse, were investigated and corrected. We read that, from December 1837, inmates should have Roast Beef and Plum Pudding for Christmas dinner and should be allowed to go out the day after Christmas from 10am till 7pm.

The work that was given to inmates varied from grinding corn, picking oakum and cotton, shoemaking and domestic work in the house and grounds, to chopping wood and breaking stones. It is not easy to determine the attitude and conduct of the Master and Mistress of the Workhouse in Tewkesbury. The local people who were Guardians of the Poor are known to us from other sources. They were some of the same people who gave generously to the charities which flourished in Tewkesbury for the benefit of the poor, especially in times of crisis like the depression in local industry and the severe weather conditions described in the article ‘On the Parish’ (see T.H.S. Bulletin, No.8 (1998), p.48). However, these kindly individuals did not have complete freedom in running the affairs of the workhouse, since there were constraints from the central authorities and they were answerable for any squandering of the Poor Rate to the local people who had elected them.

As the nineteenth century wore on, conditions in general improved, and it was realised that it was not only idleness which caused some people to fall on hard times, but the shame of having to enter its walls never left the institution.

The workhouse building was used as a geriatric hospital from 1948 until 1980, with some of the former residents staying on. One lady with experience of both institutions said, “Holm Hospital was much nicer than the Workhouse!” No-one lamented the demise of ‘The Grubber,’ as the Poor Law Union building had become known to locals.

References:

- Norman Longmate, The Workhouse (Temple Smith, 1974). Students of the Great Irish famine of 1845-1847 will know that it was the same George Nicholls who, as Poor Law Commissioner for the Whig government, was sent to Ireland in 1838 to investigate the best way to relieve ‘destitution.’ He recommended that the workhouse system of the Poor Law Amendment Act of 1834 be introduced to Ireland, with little attention being paid to the local characteristics of that country. If anything, it was to be applied more harshly in Ireland, with great problems for those affected by the catastrophe of the famine years. For further information see Cathal Poirtier (Ed.), The Great Irish Famine (R.T.E. with Mercier Press, 1975).

- From the invaluable book by ‘Tewkesburian’, They Used To Live In Tewkesbury (Sutton, 1991), we do, however, obtain a glimpse of a possible fate through an inquest of 1788 which relates to the death of Thomas Wells, a boy employee. He drowned himself rather than continue a wretched life of beating and ‘cruel treatment’ under his master, a stocking framework knitter. He had not come from the workhouse, which was not built then, but he could well have been a parish child.

- These are the Imperial Measurements: 4oz = ounce or 28 grams in metric measurements; lb = pound or approximately half a kilo; cwt = hundredweight or 5% of 1 tonne. £1 = 20 shillings and £1 in 1834 was worth approximately £43.37p in modern money. (Editor)

- Longmate, op. cit.

Comments