Living with Grandparents

home of her great-grandfather,

shoemaker John JamesClick Image

to Expand

During the Second World War Mrs Redman and her brother were evacuated from Bristol to live with their grandparents in Tewkesbury. She has kindly allowed us to print some extracts from her reminiscences, in which she has changed the names of people who may still be alive.

Our grandparents lived in one of the first council houses that had been built in Tewkesbury. They were solidly built semis, half brick and half pebble-dash, with both dining room and lounge overlooking the front garden. The kitchen was at the back and faced up the long garden that stretched to the cemetery. The front door was situated at the side of the house, but we always used the back entrance as our shoes were nearly always muddy or dusty from playing in the fields opposite, so we had to take them off in the stone passageway just inside the front door. The house was the last in a row named the Gastons [12], as they had been built on land originally called Gastons’s Meadow, where, in 1471, a final battle in the Wars of the Roses had been waged.

Upstairs there were three bedrooms and a bathroom, which must have been a very modern convenience when the houses were built. My mother and father, when he was with us, had a room overlooking the main road, and I slept in a camp bed. Our grandparents had the room next to us, where the huge bed with its iron bars and shiny brass knobs seemed to nearly fill it. My brother slept in a little room across the landing that looked out across the back garden. Downstairs were the kitchen and pantry, the dining room where we spent most of our time, and a small drawing room where Grandfather sat on Sunday afternoons reading the Methodist Recorder. He would also retire here when he had one of his headaches or wished for some peace and quiet. A few visitors were invited in here, but Roger and I were rarely allowed inside. I can just remember a Victorian what not in the corner, the shelves of which contained Staffordshire pottery figures on horseback and knick-knacks brought back from various holiday resorts.

The food, even before the days of rationing, was very plain. We found mealtimes a strain as we sat quietly while Granddad expounded some religious or political theory that we did not understand. Mother was subdued and anxious lest our behaviour should not reach the standards required by our grandparents. I do not remember being reprimanded by either of them, yet somehow they managed to instil total obedience into us. Meals started with Grandfather saying grace. Wasted food was not tolerated; every morsel had to be eaten, which I found difficult as I hated most vegetables and did not much like meat. At tea we had to eat the statutory two pieces of bread and margarine before we could have cake. Luxuries like jelly, blancmange or tinned fruit never appeared. We had to sit very still throughout meals, and we were not allowed to leave the table without permission, usually given when everyone had finished.

H.D. James was a Labour Councillor from 1933 to c 1945. In 1936 he and fellow labour Councillor Coopey fought other councillors claiming that “the Town Council had no legal power to sell the land to Messrs Healings; only power to lease it for a period up to 21 years”.[1] In 1940 he was advocating providing bathing facilities for men because he claimed that “there are 137 men living in houses with no proper facilities”.[2] Being a former Council house tenant himself in 1943 he accused housing officials of using “Gestapo methods In Tewkesbury”.[3]

He was also a Trustee of the Baptist Chapel (then in Barton Street). In 1906 he had a Distress Warrant issued against him for refusing to pay his church rates in favour of the Church of England. Eventually the law changed. [Editor]

- Tewkesbury Register newspaper, 25 Jul 1936 p5/3; they lost by one vote.

- Tewkesbury Register 22 Jun 1940 p1/1.

- Tewkesbury Register 30 Jan 1943 p1/3.

Although Granddad kept hens, roast chicken rarely appeared, as they were kept mainly to provide eggs. Sometimes Nanny would prepare a boiling fowl, usually a tough old bird that was past laying. I hated the idea of eating a poor bird that had, until a short time before, been pecking about in the hen run. The grisly method of decapitating the poor, frightened creature horrified me, and my revulsion was increased on hearing Granddad’s description of the headless corpse running round the garden.

The one food I loved and desired, but did not often get, was eggs. Granddad had one boiled for his breakfast every morning, and I would gaze longingly at it, sitting snugly in the eggcup while he cut the top of the shell off and dipped his spoon into the rich yellow yolk. Sometimes he would spread some onto a slice of bread and margarine and give it to me. I would savour each mouthful, trying to make the morsel last as long as possible. Later on, I was to have an egg every day, too, to compensate for my deprivation in the days of rationing – no worries about cholesterol to spoil my enjoyment then!

Sunday

Our grandparents lived a very rigorous existence, and they were very narrow in their outlook on life, although they were kindly in their intentions. There was no compromise in their attitude to moral standards. Both were strict teetotallers, being active members of the Wesleyan Methodist church in the town, so all intoxicating liquor was regarded as the Devil’s own brew. Any form of gambling, including raffles, was also disapproved, as were cinemas, theatres and dancehalls. When we first went to live with them they even refused to have a radio, although later in the war Father managed to persuade them to try one he had been given. It was only used to listen to the news, serious discussions or religious services and hymn-singing.

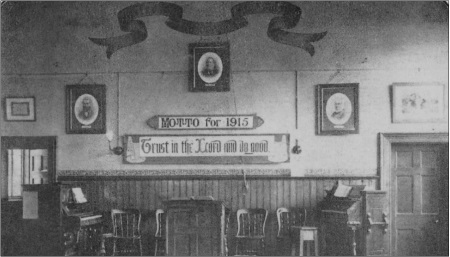

They were strict Sabbatarians, which meant that as little work as possible was done on a Sunday. Grandmother always cooked the joint and prepared the vegetables the day before, and all the household chores were done on Saturday, too, so that Sunday could be a day of rest, devoted to church-going, reading religious books and sitting in the little sitting room. Roger and I were not allowed out to play, but had to amuse ourselves quietly in the house, or in the back garden when the weather was fine. In the morning we went to church. The sermons seemed interminable, but we did not dare fidget, so we learned to sit still, thinking about other, more interesting activities.

After dinner, while our grandparents rested, we went out for a sedate walk, Roger and I leading, with Father and Mother arm-in-arm behind. We had to be on our best behaviour, and could not return home with muddy shoes or dishevelled clothes. This spoiled the joy we felt at the reunion with our father. Sunday evenings were the worst; we waved him goodbye on the Midland Red bus that took him to Gloucester, where he caught the connection back to Bristol. The awful feeling of desolation I experienced at each parting, made worse by the gloomy atmosphere of our grandparents’ home and later by the dread of school the following morning, was an emotion that stayed with me for many years.

Town Delights

to Expand

We had favourite shops which we used, usually on the way home from school, if we were lucky enough to have some money in our pockets. Halfway along Church Street there was a little sweetshop run by a lady who was related to the twins. She would give us extra, topping up our bags with more than we had ordered. There was another sweetshop on the corner of the road, opposite the Bell Hotel, where we used to buy aniseed balls that changed colour as you sucked them, striped humbugs, brightly coloured gob stoppers and shiny black liquorice pipes, covered in sugary hundreds and thousands. A bag of sherbert came with them, and it was bliss to dip the pipe into it and try to suck the powder into our mouths. My brother and I were not really allowed sweets between meals, and Mother disapproved of eating in the street, but somehow we managed to acquire our share, in spite of sweet rationing.

I cannot recall how we came by much money, as we had no regular pocket money. We were given enough for our needs, such as the bus fare home in bad weather, or the price of a cheap seat at the [Sabrina] cinema. Sometimes we had to toss up between a ride home or sweets, and often the sweets won. My brother used to earn a few shillings by helping at Gaze’s Farm, where we spent a lot of time. Even the younger ones could earn a shilling at potato-picking time, though it was backbreaking work. Another way of making a few bob was by picking rosehips and blackberries to be made into syrup or jam, or by collecting conkers that were sold for pigfood. We were encouraged to do this at school, where we were paid when we took along our baskets piled high with berries or shiny chestnuts.

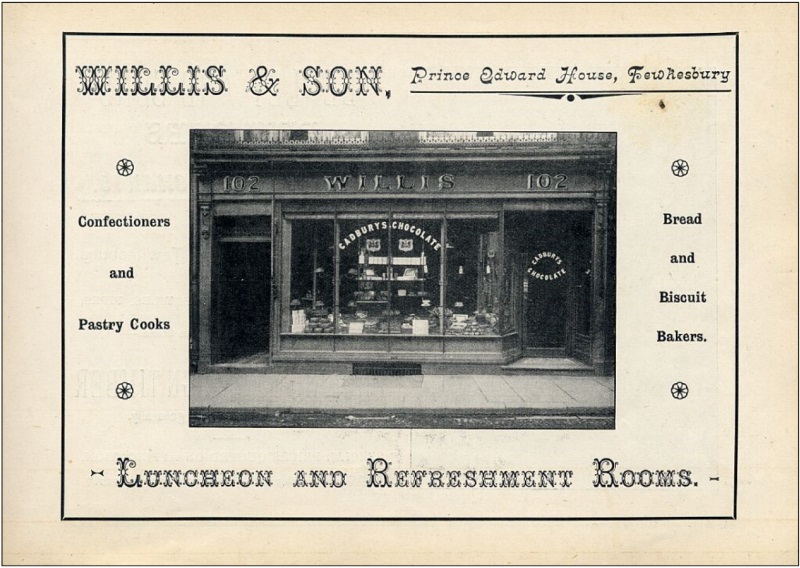

Another of our favourite shops was the baker’s by the Cross in the centre of town. It was run by the Misses Willis, distantly related to Dave’s father, and real ‘old maids’ who were regular attenders at the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel. They were friendly to us when we all trooped into the shop, ravenous after a day at school. Chelsea and cream buns, rock cakes and currant ones were laid out to tempt our fancy, but I preferred the big, square ginger slabs, which were so moist and crumbly. I remember once having just taken a huge bite out of one when our Headmaster, Mr. Gibson, cycled past and said in his deep voice, “Now, Anita, what are you up to?”

I blushed and tried to answer with a huge wedge of cake stuck in the side of my mouth!

School

to Expand

We did not pay much attention to school; it was an experience that had to be endured until we were let out at the end of the day, with the promise of Saturdays and the exhilaration of holidays beckoning, causing our minds to stray from the dreary monotony of lessons.

My brother went to the Junior School straightaway, but I had a few months grace before I was enrolled at the Infants’ School. No preparation was made beforehand; Mother simply took me along and left me there, with a horde of other five-year-olds, many of them crying, in a crowded classroom. The building was very old, and was opposite the Junior School, another old Board school building where my grandfather had been to school seventy years before. However, the red brick building with its sloping roof and Gothic windows had been requisitioned by the War Office, so all the infants were shepherded into a crocodile and marched round to the Trinity School, which belonged to the church next door.

This must have been an unexpected change of plan, for none of the teachers seemed ready to accommodate the influx of new children. We had to sit in a classroom for what seemed like most of the morning, supervised by some of the older girls. I sat there miserably, longing for my mother, and desperate to go to the toilet. Once or twice I murmured in the direction of an older girl the words Mother had told me to use, “Please may I go to the offices?”

Nowadays that seems a very stilted phrase, but the word ‘lavatory’ was frowned upon, and ‘toilet’ had not come into use; I do not recall hearing it as a child. No-one heard my embarrassed mutterings, so I had to sit in acute discomfort until playtime, when I must have found the girls’ lavatory in a brick outhouse on the far side of the playground. I do not remember anyone showing the new children its whereabouts.

My first day at school passed in a miserable daze, and the following day when Mother took my coat off in the cloakroom and made to leave I screamed and clung to her, shouting, “I don’t want to stay, I want to come home!”

Embarrassed, Mother shook herself free and handed me over to Miss Logan, my teacher. She led me, still crying, to the class room, where I eventually calmed down and accepted my fate. The infant teachers were strict and expected immediate obedience. We had to sit still and were not allowed to talk. Anyone caught talking was made to stand on a chair in front, or, worse still, habitual offenders were even put behind a net in the corner of the room. This once happened to my friend, Valerie, who was a chatterbox with a squeaky voice which carried across the classroom, to be picked up by Miss Logan’s sharp ears. I shall always remember the squeals of fear as the little girl was made to stand behind the folds of the net hanging from the ceiling in the corner.

Miss Logan wore a flowery print overall, and she had dark hair in a roll at the back. Though she had plump, rosy cheeks, her unsmiling face and pursed lips gave her a severe appearance. The children at the school were a mixture of those who came in from the country, dirty ragamuffins from the alleys, rough bullies from the council estates that were springing up round the town, and a sprinkling from the ordinary working class homes. There were two other evacuees: Clifford, who lived with a family at Southwick Park, a large mansion outside the town, and Dulcie, who lived with her uncle and aunt near the Abbey. Both of them became friends of mine, as we came the same way to school, and between us we must have been blest with most of the brains in the class. A large number of children were still unable to read when they moved to the Juniors.

I was always called out by myself to read at the teacher’s table from the incredibly boring ‘Beacon Readers’, as I had attained a much higher level than most of the others in the class. They had to stand in groups round her table, taking it in turns to read each line haltingly, and being chastised for the mistakes they made. Small wonder that many of them made little progress, and that the rate of absenteeism was high.

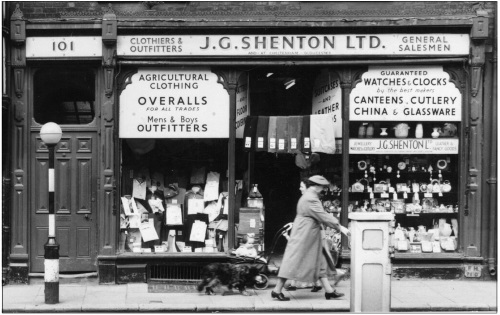

Other shops I remember in High Street were Woolworths, still called ‘The Threepenny and Sixpenny Store’, though by then many items were dearer; Peacocks, which in those days was more like a general store than it is today [it closed in 2012]; Smiths the booksellers, where I loved to browse through the books that were too expensive to buy, and another bookshop, further up the High Street, whose name I forget. It was here that I went one afternoon with my great friend, Dulcie, also evacuated and living with her uncle and aunt, who had a monumental mason’s business in Church Street. She had found a pound note on her way to school that morning, and had told me she would buy me a book if I went with her to the shop. We went guiltily into the booksellers, and I spent ages trying to decide which tempting covers appealed to me most. At that time I was passionately fond of Enid Blyton adventure stories, but I found it impossible to decide which one to choose. Dulcie, however, had bought three books with illustrated covers, and I envied her greatly. On the way home we stopped in a quiet alley, where she secreted the books inside her navy blue school knickers, which were quite voluminous enough to hide the three bulky objects, although they made Dulcie stagger along in a peculiar fashion.

The next day she met me on the way to school with the news that her aunt had discovered the secret, and had insisted that the books be returned and the pound note handed in at the police station. I was to call in at the shop on my way home, where Dulcie’s aunt gave us both a lecture on honesty and truthfulness, something I had heard many times before, from my grandparents and from the pulpit in church. We were both made to feel rather ashamed of ourselves, but I must admit that the temptation to buy things we desperately wanted at a time when children had little spent on them was very great.

to Expand

Near the Cross was a gentleman’s outfitters that had been a hat shop. A large model of an oval black hat, shaped like the one worn by my grandfather with his robes of office at special Council occasions, hangs outside it to this day [The Hat Shop – now ‘Heritage Center’]. Sandwiched between this shop and the milk bar frequented by American soldiers and their girlfriends was a strange little shop owned by an old lady named Miss Reeves. It was a drapery business that sold everything from buttons and ribbons to hosiery and lingerie. Much of the clothing on display, both on shelves and beneath the counter, was about forty years old, and included lacy drawers, petticoats and camisoles that young ladies would have worn more than half a century before. Miss Reeves also sold men’s long, thick combinations, which my grandfather wore in cold weather, and Mother sometimes bought thick underwear for us there, like liberty bodices and vests with sleeves. Miss Reeves was nothing if not patriotic, and in order to persuade people to give generously to fund-raising events like ‘Wings For Victory’ or ‘Salute The Soldier’ weeks she put a large notice in her window, saying ‘Don’t be a miser! Turn out your stockings and drawers’! She little knew what amusement this caused!

She also refused to serve evacuees, regarding them as agents of Hitler and traitors to the cause, scrutinising all those who entered the shop through thick pebble glasses to see whether she recognised them. At first she treated Mother in this way, but relented when she discovered who our grandparents were.

Halfway along the High Street, just before the Town Hall, was a dark little shop owned by Mr Evans. It was a shoe shop, but the boots and shoes on display inside were so covered in dust that it was clear turnover was not rapid. He, too, attended the Methodist Church, with his unmarried daughter, Winifred, who also served in the shop. Mr. Evans was Welsh and spoke with a pronounced accent. Round-shouldered, he had a droopy moustache and an ingratiating manner, coming out through the heavy curtain that separated the shop from the living quarters with head bowed, rubbing his hands together as though expecting a transaction. Father’s nickname for him was ‘Great ’eavens’, as that was a phrase frequently occurring in his conversation. His daughter had a gushing manner that belied an awkwardness in meeting people. Her mother was dead, and she lived alone with her father, caring for him and doing the housework as well as serving in the shop. She was tall and thin, with horn-rimmed glasses that gave her an owlish appearance, and when she smiled she revealed a large set of teeth and a wide expanse of gum. We rarely bought any-thing in the shop, but my father went there out of loyalty to an old man he had known since boyhood. When we needed new winter shoes (lace-ups with toecaps for my brother, and a pair with a bar that but toned across for me), or sandals for summer, it usually meant a trip to Cheltenham or Gloucester where there were more shops.

Other shops I can remember were Watson’s the jewellers and clock shop, Bannister’s the chemist, and Oldacre’s, a big shop on the corner of Oldbury Road that sold seeds, fertiliser and animal feed. On the way home from school, Mother might stop at Mr Brick’s, the cobbler in Station Street. I was fascinated to watch the old man, bent nearly double with arthritis, select a large piece of leather, cut out the shape to match the shoe in his hand, then, after pulling off the worn sole, start to hammer in the nails that he held in his mouth. This all took place not far away from the old house at the top of High Street where John James, my great-grandfather, had worked at his cobbler’s last more than seventy years before.

Comments