‘A Stitch in Time’

Tewkesbury’s 17th and 18th Century Stocking Manufacturers

Tewkesbury was typical of many market towns with many craftsmen running small businesses and some larger merchants.[1] However, it did have important staple trades: indeed, much of Tewkesbury’s prosperity during the medieval period was from the manufacture of wool. However, this was in decline by the beginning of the eighteenth century. The town had been important in the seventeenth century, as it was second in the county in size and wealth to Gloucester.[2]Unfortunately Tewkesbury could not compete with Bristol and Gloucester.[3] The decline of the traditional industry caused mass unemployment; the affected individuals were encouraged, instead, to knit woollen and cotton articles of clothing.[4] This resulted in Tewkesbury becoming associated with the trade of hosiery or stocking manufacture. Peter Clark suggests the town had a prosperous hosiery industry from the Stuart period,[5] although this was poorly paid.[6] The industry later became mechanised; Robert Campbell wrote that stocking frames were a new invention in London in 1747, but new equipment and methods of working would have taken longer to reach the provinces.[7] In 1774, Tewkesbury was described as being “a large, beautiful and populous town, of which the chief manufacture is woollen cloth and stockings”. This suggests two types of articles were being produced: woollen cloth would have been woven on a loom, whilst stockings in the early period were knitted by hand. Nonetheless Pugh points out that the town was not dependent on this one trade as there were ‘other major industries’ that together provided affluence; these were malting, leather production and the corn trade.

Anthea Jones suggests that “Tewkesbury’s most prosperous time was before 1820, when framework knitting employed the poor, and the inns and markets provided for as well as reflected the prosperity of the commercial classes”. The change of industry transformed the nature of habitation in the town. The previous system of working in the master’s house ended, and employees knitted in their own houses. Evidence of stocking manufacture can be seen from the large windows in the upper storeys and garrets of a number of properties in the town. These were to maximise the amount of daylight and hours that could be utilised. Likewise probate inventory evidence records a number of looms. This is similar to Norwich, where weavers employed in the town’s staple trade were documented “in their garrets at their looms.”[8] Stocking knitting and weaving increased the number of dwellings in Tewkesbury’s ‘poverty-ridden’ alleys. There are two men whose probate documents survive that bring home the conditions and lifestyle of those in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries that made their living from the manufacture of hosiery. However, these inventories and wills pre-date the mechanised industrial revolution.

into the spacious and attractive dwellings of today Click Image

to Expand

The earliest probate documents date from 1663; these belonged to Robert Mopp. His occupation was described as a labourer, but like many he worked in more than one trade. (Inn holders frequently operated shops from their premises.) Mopp’s occupation identified him as being at the bottom of Weatherill’s social status hierarchy, which had identified the gentry at the top, yeomen, tradesmen, husbandmen and labourers.[9] Labourers were also near the bottom of Weatherill’s consumption hierarchy, but they owned more domestic goods than husbandmen did. Mopp’s stocking-making was no doubt a part-time occupation, as his inventory recorded “woolen and lynon half shoes and stockings”. As no loom was recorded, it is likely that these were knitted. Probate assessors would have ignored knitting needles as too low value to mention along with other small articles such as combs that would be categorised as ‘other lumber’.

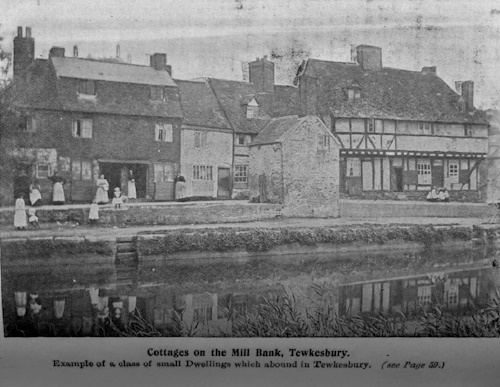

Although Mopp’s status was lowly, he did own his home on Millbank.[10] The location of properties was rarely recorded in probate documents as the assessors knew where the testator had lived. His house was small, at most consisting of two rooms; his ground floor was described as a “lower roome being his hall and kitching”. By the eighteenth century the two-roomed cottage was something of a rarity.[11] Mopp’s inventory illustrates the harshness of life in the early modern period. Carol Shammas insists that a characteristic of the early modern period was a lack of equipment for proper polite dining and insufficient furniture and utensils for the sociable side of domesticity. She argues “in effect, all the valuables in the house could be quickly grabbed and stuffed into chests without fear of breakage or of great expense of moving”.[12] This dwelling had one hearth on which to heat and cook. The hearth tax returns illustrate that the majority of housing in Tewkesbury consisted of one-hearthed dwellings. Many of the inhabitants of these were granted exemption from paying tax due to poverty.[13] Living conditions in the last quarter of the seventeenth century in Tewkesbury were challenging for the majority of people.

Robert Mopp’s small home was a common type of dwelling in the late seventeenth century. These would have been half-timbered and in many instances poorly built impermanent structures that only lasted a generation or two.[14]These small properties did not often survive as when Tewkesbury grew the plot was used for larger buildings, especially if the artisan houses were located on desirable land. However, the photo of circa 1900 depicts buildings of a range of ages on the Millbank, including in the middle a small property that may have been a two-roomed house of a similar size and style to the one in which Mopp had lived.

The main area of Mopp’s house was his hall; this was the main working, eating, cooking and sitting space. The furniture of this area consisted of a table-board and three joined stools, whilst his cooking equipment consisted of a brass pot hung over the fire and a frying pan. Mopp most likely had spits to roast meat above the fire, but he had no oven, which restricted his diet to fried food and roast meats (if he could afford it). The main types of warm food, devoured during the seventeenth century amongst the lower ranks, were stews and soups.

Mopp would have worked long hours; when he slept it was in an uncomfortable bed. Beds were important pieces of furniture and reflected the wealth and status of their owners. However, not everyone could afford to invest in an elaborate and expensively furnished bed, as Carole Shammas states: “the soft, warm decorated bed was an isle of refuge in a household sea of discomfort”.Mopp’s mattress was not of the poorest quality as this was chaff [straw]. His mattress was made from flock; this usually meant it was stuffed with rags[15] or wool refuse from shearing off the nap.[16] The best mattresses were filled with feathers. Sheets were an important part of the comfort of the bed. They frequently were recorded in pairs. An under-sheet helped prevent the mattress filling from sticking into the sleeper, whilst the upper-sheet shielded the person from the rough texture of woollen blankets. Mopp’s sheets were of hemp, which was hard wearing and resembled linen.

He did not seem to have his own family as his property and goods were bequeathed to his brothers and their children. Mopp had three brothers; John Mopp the elder was given the house on Mill Bank. The other two brothers had £13 each. This most likely was his life savings, £26 of “readie mony in purse” was listed in his inventory. Reliance Mopp received £13 to pay for the apprenticeship of his two sons. The purpose of the money given to John Mopp, the younger, was not recorded. (Two of his brothers had the same name.)

Mopp seemed to be used to discomfort, or maybe religious fervour made him embrace it: the tone of his will implies he had strong beliefs. Mopp’s everyday clothes were of a functional and basic nature, owning “a piece of hempen cloth enough to make two shirts”. This hardwearing material had the advantage of going whiter with age rather than discolouring.[17] Mopp’s brother, John the younger, was to receive these day-to-day garments. His best suit of clothes was given to his brother, Reliance, consisting of “two coats, doublet, pair of hose and a waistcoat”.

Robert Mopp was not a wealthy man and he appeared content with his station in life. His employment in the two trades of a labourer and a stocking knitter brought its own rewards. Mopp owned his two-roomed cottage and had enough household goods and clothing to fulfil his needs. He was also able to save the respectable sum of £26.[18] This could have been spent on improving his domestic environment, but instead this was given to his brothers and nephews.

The other surviving probate documents that provide an insight into the stocking trade are those of a hosiery seller and weaver Tobias Needham, the elder. His inventory was valued at £55.2s.9d [£55.14p]; this, along with his will, was proved in 1712.[19] Campbell suggested that the trade of hosi-ery selling needed no apprenticeship, as all that was required was the knowledge of buying and selling.(However, Needham was made a ‘freeman’ after completing his apprenticeship as a ‘jerseyman’ in 1769 and he and his son trained at least 6 apprentices between 1679 and 1753.[20]) Freeman status was conferred on those that finished their apprenticeship or it was given to the children or grandchildren of freemen. This status conferred certain rights, such as the right to trade, own property and have protection within the town.

Needham is an example of a lesser tradesman who operated a shop. Shop keeping was common amongst those whose properties faced on to major or minor streets. The term ‘shop’ was interchange able with ‘workshop’ so these were places of manufacturing as well as retailing. Trades such as dyers, nail makers, weavers, braziers and basket makers all were recorded as possessing shops.

by the Landmark Trust (Reg Ross, 1986)Click Image

to Expand

Needham’s list of trade goods illuminates the variety and quantities of woollen yarn used in the manufacture of stockings, along with some finished articles of heavy wool cloth and hose. The spellings of words in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were not consistent, many words were spelt phonetically and there were also regional variations. In his shop was:

- 21 £10.0s.0d.

- 100 yards of druget[22] £5.16s.8d.

- 48 pounds of double woosted23 £7.0s.0d.

- 46 pounds of single woosted £4.4s.0d.

- 29 cwt. of woollen yarn £1.14s.0d.

- Woosted wooll & woollen yarn £2.3s.6d.

- 24 pair of woosted hose £3.10s.0d.

- 30 pair of hose woollen £1.10s.0d.

Needham used his shop for the selling of finished cloth and hose as well as for the storage of yarn that had to be woven. Stockings that were woven rather than knitted would have had less stretch, but may have been cheaper. He may have sold yarn to other stocking manufacturers, or paid outworkers to complete goods as his shop contained £30.18s. of various types of yarn and cloth valued by weight and length. There were fewer finished stockings for sale, as there were only two sorts (worsted and woollen); they were valued at £5.

Needham made his wares in his working shop, as he owned two looms, a twisting mill, a warping bar, a beam and scales and other utensils. He would have spent a large amount of his time in this room. This is suggested by the pot and links that would have allowed him to heat stews over the hearth that also heated the working shop. The other outbuilding was described as a “backhouse”; inside here was a furnace, brazing tack and coal. Needham may have supplemented his income by using the furnace for brazing or metalworking such as nail making.

Needham would have had assistance in operating his trades, as it could not have been a single man enterprise. He could not have run the shop, and woven in the working shop and brazier in the back house. Unlike Mopp, Needham had immediate family. He was a widower with four children, but it is apparent that relations between his family were not all cordial as one son was cut off from his estate with a shilling [5p]. His daughters fared better as they were to be paid ten pounds each. As Needham had only £2.10s. [£2.50p] of money, trade and household goods would have had to be sold to raise the sums of money. Tobias his other son, created a freeman in 1700, was to receive everything else and to be executor.

Palmer and Neaverson point out that the surviving homes of handloom weavers often show little evidence of their previous use before the nineteenth century, but there are exceptions.[14] This photo of the later eighteenth-century stocking weavers cottages show the large windows that were inserted to maximise the amount of natural light and hours that could be spent at the loom.

The value of Needham’s household goods was low being £9.4s.3d. [£9.21p]: there appeared to be little domestic space as his inventory lists only his kitchen and bedroom. The contents of the downstairs room were as sparse and comfortless as Mopp’s: similarly all necessary and sociable activities took place in the one main ground floor room. The house, like Mopp’s, appeared to have only one hearth. There were hardly any distinctions in living standards that marked the fifty-year time difference between the two documents, apart from storage furniture in the form of a “press cubard” in the kitchen[25] and a side cupboard in the bedroom. The bedroom provided more comfort in the form of a bedstead with a feather mattress. This was also equipped with bed curtains that provided warmth and privacy. These may have been needed as the room was shared with at least two other sleepers who had flock mattresses on the floor.

Needham’s probate documents illustrate the diversity of the stocking maker’s trade by providing an insight into the types of yarn and equipment that was needed. Despite the low monetary value of Needham’s goods, his and his son’s status as freemen would have given them a certain amount of status in the town. Also the Needhams were well-established stocking manufacturers, and were skilled and trained artisans. Tobias Needham the younger would have lived to see the beginnings of the mechanisation of his trade that would have changed his traditional way of life.

Together the two stocking makers’ inventories and wills highlight that whilst a living could be earned from this trade, fortunes were not made. However, employment in the stocking trade provided self-sufficiency and the means to make ends meet. Both Mopp and Needham were able to afford some material comforts in the type of beds that they slept on, at a time when people mainly owned only functional objects in their homes. The accumulation of a lifetime’s work allowed Mopp’s and Needham’s families to benefit from the legacies they left. Needham’s employment in the stocking trade had wider ramifications, in the form of the knowledge and training he passed on to his son and six apprentices. The probate documents of Mopp and Needham open a window on to life in the mid seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, by providing a glimpse back into an important aspect of Tewkesbury’s history.

References

Karen Banks studied for a PhD at Wolverhampton University, focusing upon the towns of Tewkesbury, Hereford and Ludlow between 1660 and 1760. Karen is married with four children and lives in Bridgnorth, Shropshire. Karen’s last two articles have been shortlisted for the last two county Jerrard Awards.- Anthea Jones, Tewkesbury, Phillimore, 1987, p.81-82.

- Andrew R. Warmington, Civil War, Interregnum and Restoration in Gloucestershire, 1640-1672, Boydell Press, 1997, p.15.

- Peter Ripley, ‘Village and Town: Occupations and Wealth in the Hinterland of Gloucester, 1660-1700’, The Agricultural History Review 32, 1984, p.173-78.

- Ralph B. Pugh, ‘A History of the County of Gloucester’, Victoria County History Vol. 8, Oxford University Press, 1968, p.111.

- Peter Clark, The Cambridge Urban History of Britain, Vol. II, 1540-1840, Cambridge University Press, 2000, p.750.

- Kathleen Ross, The Book of Tewkesbury, Barracuda, 1986, p.43.

- Robert Campbell, The London Tradesman, T. Gardiner, 1747, p.214.

- as in footnote 4 above.

- Lorna Weatherill, Consumer Behaviour and Material Culture in Britain 1660-1760, Routledge, 1988, p.171-5, 185.

- Will of Robert Mopp, labourer, proved 1663 (Gloucestershire Archives [GA] 1663/147; a translation can be studied at the Town Library in C. Talbot & J. R. Rennison: Transcripts of Wills of 16th & 17th Centuries).

- N.J.G Pounds, The Culture of the English people, Cambridge University Press, 1994, p.419.

- C. Shammas, ‘The Domestic Environment in Early Modern England and America’, The Journal of Social History, 1980, Vol.14, p.8 & 10.

- Gloucestershire Hearth Tax 1671-72 (GA D383).

- Carole Shammas, The Pre-Industrial Consumer in England and America, Claredon Press, 1990, p.6.

- Barrie Trinder and Nancy Cox, (2000), Miners and Mariners of the Severn Gorge, Phillimore, p.64.

- N.W. Alcock, (1993), People at Home, Living in a Warwickshire Village 1500-1800, Phillimore p.223.

- ‘Hemp-Herse’, Dictionary of Traded Goods and Commodities, 1550-1820 (2007). URL: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=58791 Date accessed: 23 October 2011.

- [Editor: Depending on the index used, in 2009 £26 could be worth between £3,220 (prices) and £41,100 (earnings): URL: https://www.measuringworth.com/]

- Inventory of Tobias Needham, a lower middling rank Tewkesbury hosier, made 1712 (GA 1712/515).

- Tewkesburian (Norah Day, 1991, They Used To Live In Tewkesbury, Sutton, based on GA research in A4/1-A4/4.

- Serge – a material made from twilled worsted. John S. Moore, (1976), The goods and chattels of our forefathers: Frampton Cotterell and district probate inventories, 1539-1804, London and Chichester, p,326.

- This may have been drugget – a wool textile used for coats. Barrie Trinder and Jeff Cox, (eds.), (1980), Yeomen and Colliers in Telford: Probate Inventories …-1750, Phillimore, p.471.

- Worsted – a well-twisted yarn from longstaple wool. Trinder and Cox, (eds.), (1980), Yeomen and Colliers in Telford, p.476. [Editor: a yard of imperial measurement = approx. 1 metre; 1 pound = 0.5 kg; 1 cwt. = 56kg; the pre-decimal coinage was £.shillings.pence (denarius)]

- Marilyn Palmer and Peter Neaverson, (2004), ‘Home as Workplace in Nineteenth-Century Wiltshire and Gloucestershire,’ Textile History, Vol. 35, p.29.

- This was like a wardrobe with shelves that allowed more convenient storage than trunks.

Comments