My Relation: the ‘Notorious Highwayman of Tewkesbury’!

to Expand

This story commences around 1771, in the medieval town of Tewkesbury, at a time when the population of this town numbered around 3,768 inhabitants. Many of the townsfolk were then engaged in working as waterman/boatman on the river systems that surrounded the town.

James Staite, who was also known as Turner Staite, was born on 27 April 1777. He was the son of William Staite of Tewkesbury and his wife, Ann (née Turner),[2] who were married on 25 August 1771 at Tewkesbury, in the presence of Thomas Cox and John Allen.

Lydia Bishop was born in 1776 in Tewkesbury. She was the daughter of George and Hannah Bishop (née Adney), who were married at Tewkesbury on 2 July 1769.

James Staite and Lydia Bishop both lived in the Parish of Tewkesbury prior to their marriage in 1797. It would appear from the baptismal registers that James plied his trade as a boatman/waterman on the rivers Severn and Avon. This occupation was associated with families living in small streets near the rivers. Most of the boatmen/watermen did not own their own boat. It was also known to have been a dangerous occupation with many of them dying either through drowning or through exposure to the elements. I imagine that winter on the rivers even in the south of England would not have been pleasant working conditions.

During this period of time, a boatman/waterman was able to ply his trade without the imposition of tolls on the Severn. This situation came to an end in 1842. Tolls were then introduced, by commissioners, in order to assist the navigation of the river and one can appreciate that this affected the livelihood of boatmen. Tewkesbury, being the meeting place of both these rivers, enjoyed a lively landscape of boats carrying goods to and from the town. Tewkesbury had an important place in the trade on the Severn during the 18th century, with considerable traffic in barges, frigates and trows.

The economic importance of Tewkesbury, through most of the town’s history, has resulted mainly from the navigability of the Severn, enabling the grain of the neighbourhood that was brought to market there, and the malt, textiles, and leather goods manufactured there, to be carried fairly easily to the coast.[3]

Today the River Severn is a peaceful place where canal boats moor as they journey along the river, floating from village to village. It is hard to imagine the hustle, bustle and noise of this river from James and Lydia’s time.

James Staite married Lydia Bishop at Tewkesbury Abbey on 2 June 1797. On the marriage register, James and both witnesses were unable to sign their names, whereas Lydia was able to sign hers. This begs the question, was Lydia in a minority of women who had been educated enough to be able to read and write, or was she only literate enough to be able to sign her name?

Richard, the sixth of seven children (and the third son) of James and Lydia, was baptised, along with his brother John, at the Abbey on 5 February 1817. His father’s occupation was again recorded as ‘waterman’, living in High Street, Tewkesbury, at the time.

Life must have been going well for the Staite family in 1817 at the time of the baptism, as the street address given would have been in the better part of the town of Tewkesbury. It was one of the main areas of town and, as such, it would have been out of the flood zones of the town. “The High Street is a spacious and well paved street; it is wide and elegant and leads from the centre of town towards Worcester.” [5]

inhabited by watermen in 19th C

However, between 1817 and early 1830, a time span of just thirteen years, something must have gone horribly wrong for this family in Tewkesbury, as it is next mentioned not only in the front of the Abbey Church Registers for this time, but also in the local Yearly Register and Magazine!

Local Memoranda: - Jan 6 – At the Tewkesbury Epiphany Sessions, Richard Staite, * aged 18, and John Potter, aged 19, were each sentenced to seven years transportation, for stealing, at a public-house in Barton Street, a ?5 bank note, a sovereign, and other monies, from the person of Charles Stephens, a farmer, of Alderton.

The bottom of the page has the following footnote:

*Staite was an expert pick-pocket and a notorious highwayman: he was a native of this borough, and was the youngest of three brothers, all of whom were transported within a short period. John was transported for life at, Gloucester Lent Assizes, 1830; and Edmund was transported for fourteen years at the Worcester Epiphany Sessions, 1832; a sister was also tried at Tewkesbury Easter Sessions, 1831, for robbing a farmer of forty pounds, but acquitted, owing to some defect in the evidence.[6]

We can only suggest that the catalyst for the apparent downfall of the family could have been the death of the family’s father, and main breadwinner. There is a James Staite listed on the Index of Burials recorded after 1812, being buried on 2 May 1823. He was aged 53 years.7 It is yet to be proven, however, whether this is the correct James Staite.

Throughout the early 19th century, Tewkesbury began to experience an economic depression because of depressed prices for their knitted stockings, which was a staple industry. Accompanying this, the town was also beginning to feel the effects of the changing transport system. Companies were no longer reliant upon the river systems for transporting their goods, rather choosing the railway and stage coaches that were proving cheaper and abundant. It is recorded that at the time, more than 30 stagecoaches were passing through Tewkesbury per day.

In conjunction with all this, there was an increase of nine inns and fifteen taverns within the local area. Rioting and unrest was prevalent due to the low wages of the majority of workers. A new gaol, replacing the local Belfry, had been constructed in 1816 with the addition of a more punitive treadmill, installed for the criminals to ‘work’ in 1828. There were 82 people committed to the gaol in this year alone.[8]

It is against this background that John, Edmund, Hannah and Richard Staite were arrested and sentenced. It would seem, however, that they were all guilty of more than one offence throughout this period in Tewkesbury’s history.

John Staite

to Expand

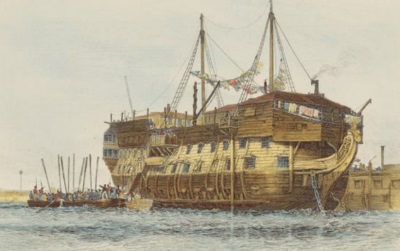

John was actually the first of the siblings to have a ‘run in’ with the law of the day. Initially in 1829 he was remanded for larceny but continued to be apprehended throughout 1830 and was brought before the Lent Assizes in April the same year. The result was that he was awarded the death penalty, which was then commuted to ‘Transportation for Life’.[9] He was first taken to a ‘hulk’ in Falmouth before being placed on the convict transport Persian and sent to Hobart, Van Diemen’s Land, for the remainder of his life.

Even in Tasmania, John did not take to being a convict particularly well and was continually brought in front of the constabulary as being of “very bad behaviour”. Hobart did not soothe his anger either and he was often mentioned in the reports as being either placed into solitary confinement, hard labour in a chain gang, or receiving lashes from the cutlass.[10] John’s convict record identifies him as having:

Dark curled hair, light grey eyes very far in his head, pale complexion very much marked with the smallpox, large nose scar and eye L brow, a scar under left eye and a large mole left side of his navel, and a mole near the bottom of his belly. Third finger of left hand has been injured at the end. First finger on (?) hand has been injured tis crooked in consequence near lower joint, first finger left hand scar left thumb large scar. Rt. knee full breasled, read and write. Nailor. Height 5' ¼.[11]

John was eventually granted a conditional pardon, which was granted on the condition that the convict made no attempt to return to England or Ireland. He was assigned to many different places and people. Initially he was assigned to Public Works. This was followed by being assigned to a William Dutton. He was then assigned to a Mr. W. Malcolm. John eventually received his ‘ticket of leave’ and, after this, had no offence recorded against him. Subsequently, however, he disappeared from all records so unfortunately we do not know what became of the remainder of his life in Tasmania. It may be that an exemplary life went unrecorded!

Edmund Staite

John was not the only family member to attract the attention of the law in Tewkesbury: brother Edmund was the next. He was involved in “an affray in which one was killed” outside the Farriers Arms Inn, which continued on into the Swilgate Meadow. He was apparently one of two ‘seconds’ (supporters) to two fights from the nearby village of Chaceley. He was arrested, charged with manslaughter, and brought before the Midsummer Sessions for his part within this quarrel. He was, however, acquitted of this charge. Nevertheless, a year later, he was once again brought before the courts for receiving stolen goods. Edmund was subsequently convicted and received a sentence of 14 years “beyond the seas”.[12] Unfortunately he died in gaol, before his ship left for Australia.Hannah Staite

Hannah was the only daughter of the family that found herself in trouble with the law of Tewkesbury. She was brought before the courts on two occasions during 1831. Her first offence was for larceny and her second offence for being “disorderly at a late hour”. She was acquitted on both counts.[13] At this stage she was aged 17. I have not followed along with Hannah’s story. Hopefully she married and there are some descendants of hers still residing in the Tewkesbury area (I would like to think so).Richard Staite

A man of many surname spellings, through my research, I have found him mentioned with any of the spellings listed above (footnote 1) – it has taken quite a while to follow his trail.

Richard is the last Staite family member to come to the attention of the law in Tewkesbury: the “notorious highwayman and expert pickpocket”![14] He also followed his siblings into attracting the attention of the Tewkesbury constabulary, appearing many times before he was finally sentenced to serve time “beyond the seas” in Australia. Richard first came before the courts in 1831 but was not convicted. He kept trying his luck until it finally ran out when he was convicted in January 1832.[15] Richard’s convict record identified him as having:

Auburn hair, grey eyes, ruddy, much freckled complexion. He was 5'10" in height. He has a scar on back of left thumb, mark of a burn on left cheek under whiskers.[16]

Richard Staite was held on board the Hulk Justitia – he was one of 10 prisoners received on 21 January 1832 at Woolwich before being transported. One of the other prisoners that arrived at the same time was John Potter, Richard’s accomplice in Tewkesbury. Richard was subsequently transported on 3 July 1832 while John was transported on 22 November 1832. Their conviction notice on the Hulk receiving paper states that they were convicted of stealing from a person a £5 note; a £1 note; 2 halfpennies; 5 shillings; and 5 sixpences.[17]

Richard spent around six months on board the hulk. The idea of housing convicts in hulks came about in 1777 when Parliament passed a motion to provide hard labour at home by housing the convicts on board the hulks. These were usually old warships that were no longer sea-worthy so were anchored along the Thames Estuary or Plymouth Harbour. They held the convicts awaiting transportation until they were transported.

Throughout the time on the hulks, which were grossly overcrowded and where outbreaks of disease were commonplace, the convicts were held in ‘irons’ and subject to hard labour usually on shore. Longboats would row them on each day to be put to hard labour upon the shores of the Thames, or any other public works, in order to clean the river. Some of the labours that they were involved in were:

loading and unloading vessels; constructing or repairing public works; excavating; tacking or carrying timber; painting ships; cleaning cables; and scraping shot

By the time that Richard was held in 1832, this style of work was commonplace.

The conditions aboard these hulks were less than ideal. The food was poor, the provision of food being contracted and rationed. A typical ration was supposed to be one pound of beef on four days and 4 oz. cheese for three days with a daily allowance of 20 oz. of bread. There are numerous accounts that testify to the fact that the food was usually inedible and unwholesome.

The Justitia was a vessel of 260 tons and housed up to 256 prisoners with two decks used for accommodation. In addition to this it housed up to 40 officers.

There were three tiers of hammocks, one over the other in each division. … One deck scarcely high enough to allow a man to stand upright, had to serve for the prisoners; the officers lived in cabins in the stern.

On board the Justitia it is reported that there was one ‘gangsman’ or ‘wardsman’ to every 16 prisoners.

The overseers were generally regarded as brutal and uncaring, one convict by the name of Vaux describes them as being … ‘guards of the lowest class of human beings … wretches devoid of all feeling; … ignorant in the extreme, brutal by nature …’[18]

Hulks have often been referred to as “chambers of horror”. In 1832, the year that Richard was aboard, the Justitia was subjected to an epidemic of cholera, with the result being a large loss of life. In later years, in the 1840s the Justitia became renowned for its unhealthy and dirty state.In 1832 Richard was transferred to the Parmelia convict transport, which left from Sheerness on 28 July 1832 and sailed direct to Sydney, where it arrived on 16 November ? a journey lasting 111 days in total. It was a barque built in Quebec in 1825 and weighed in at 443 tons. The master was James Gilbert with the surgeon being listed as Richard Allen. The Parmelia left with a total of 200 male convicts on board; with four deaths recorded on the journey it arrived with a total of 196 male convicts landing. Two convicts had died from Cholera before the ship had left England.[19]

As a general rule, the ships that were being used as transports for the convicts during the period 1830 to 1840, were those that were too old and slow to be used as an emigrant ship. They were generally dark, evil-smelling and poorly ventilated. The passage was also hampered by the lack of competence of the sailors and their mutinous ways. It is reported that the masters of the transports had more trouble controlling their sailors than they had with the convicts that they were transporting. There were also a number of shipwrecks attributed to the lack of knowledge of the crew during this period.

The food, however, was a different matter. The rations were adequate and regarded as of better quantity and quality than those on the early emigrant ships. Scurvy was still a real issue on board these passages and convicts were given lime juice as a preventive to this disease. Dysentery was also a major disease that faced the convicts aboard these ships. Richard was lucky as the surgeon on the Parmelia believed that dysentery was a contagious disease and sought to isolate any person showing symptoms – a forward-thinking surgeon for his time. It was considered a good passage if the ship arrived at its destination during this time with the number of deaths on the passage being less than three.

When Richard sailed on the Parmelia, he was leaving during a time when the issue of the transportation of convicts to Australia was under attack in England. It was also a time when the first government-assisted emigrants bound for Australia were leaving England, creating a shortage of suitable vessels. Among the other convicts on board were those that had been involved in the famous Bristol Riots in October 1831.

After Richard finally sailed into Sydney Harbour, the convicts were to remain on board the Parmelia for another two weeks, sitting in Port Jackson Harbour, before they were finally disembarked. During this time, a detailed record of each individual’s physical appearance was undertaken. A hazy Sydney day, with a top temperature of 71°F, was the day for finally setting foot on land in his new country, Wednesday 28 November 1832. He would have looked quite a sight, as most of the convicts were still wearing their own clothes, and most of them would not have had a change of clothes. This in itself would mean that they would have been an untidy, smelly sight!

When the convicts were landed in Sydney Town, the Sydney Morning Herald ran a story reporting that the convicts arriving were “Young active men who would be an acquisition to the settler”. Richard was taken to Hyde Park Barracks, where he would remain until he was disposed of to a Mr. James Quinn, a resident of Sydney.

Richard’s first few days or weeks were spent at these barracks in Macquarie Street, Sydney. At the time there would have been between 600 and 1,200 other convicts staying at the barracks. Here they were put to work, having to answer to the Superintendent, the convict constables and the other overseers. They were known as ‘Government Men’. Their work consisted of hard physical labour, such as making bricks, constructing buildings or roads, or tending the gardens. Their work day began with a bell ringing in the barracks to call them to rise for the day. This bell also controlled their life, telling them when to eat and when to go to bed of a night. Their working week consisted of six days, working from sunrise to sunset. Allowances were made for extremely hot weather, when they were provided with an hour’s break at lunchtime. The only day each week that they were not expected to work was Sunday, when they were required to attend Church.

Richard went on to marry Sarah McManus, daughter of James McManus, a marine, and Jane Poole, a convict, both sailing with the ‘First Fleet’ to Australia. They had nine children and moved to a settlement on the western side of the Great Dividing Range, called Meadow Flat, in New South Wales. Richard’s life ended tragically, just seven months after the birth of his last daughter, when he was accidentally killed as a result of being thrown by a horse. He died at ‘Woodside’ near Bathurst on 16 July 1857. He was aged 46 years.[20]Lydia, Ann, Hannah and William Staite

Little is known about the remainder of the Staite family left behind in Tewkesbury. What we do know is that, in 1833, Lydia and Ann Staite were both living in Eagles Alley. They were both receiving Parochial Relief from the Church; Ann is listed as being lame. They would have been part of the 233 heads of family who were receiving ‘outside the workhouse’ relief from the Parish. In 1833, £3,143 was spent on the poor of the Parish.[21]

Reflection

It is hard to place myself in Richard’s time in Tewkesbury. I imagine that life became quite challenging for the family, hence three of the boys being convicted to ‘transport across the seas’. I feel that Richard made good of this sentence and settled in Sydney for the majority of his time in Australia.

His move to New South Wales offered a chance of living on and owning farming land in a new developing area. This would have been, I imagine, a dream come true – something that would have been unachievable if he had remained in Tewkesbury. The weather of this area would have had some similarities to his home, with cold winters and ample rainfall. The hope, ambitions and challenges for him relocating his family to Meadow Flat, was unfortunately cut short as he was killed not long after moving to this area. It is sobering to consider that this man had cheated death by disease, throughout his time on the hulk as well as during the voyage to Australia, yet an unfortunate accident cut his life so short.

My dream is to meet, on my next visit to Tewkesbury, some other Staites that have descended from this family. During January my family and I will be travelling again to Tasmania and I will endeavour to follow on John’s trail … hopefully another chapter awaits.

References

- The spelling of the name varies considerably: Staight, Straight, Staite, Stute, State and Stait. However, for the purpose of this article, the name Staite will be used.

- All BMD information is extracted from the relevant Tewkesbury Abbey Parish Register.

- British History Online, ‘The Borough of Tewkesbury: Introduction’, A History of the County of Gloucester: Vol. 8 (1968), pp. 137-146, www.british.history.ac.uk

- British History Online, above; pp. 165-167, Schools.

- James Bennett, Bennett’s History of Tewkesbury,1830, Tewkesbury. [The Editor is less sure as the family may have been living in one of the alleys leading from the High Street – which were neither “well paved” nor “spacious”.]

- James Bennett, Tewkesbury Yearly Register and Magazine, Vol. 1, 1840, (High Street, Tewkesbury) p. 85.

- Index of Burials recorded in Tewkesbury after 1812.

- British History Online, above; pp. 122-131 & 137-146.

- England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791–1892, www.ancestry.com

- New South Wales and Tasmania Australia Convict Musters 1806-1849 for John Stait.

- England and Wales Criminal Registers 1791–1892: The National Archives of the UK (NA), Kew.

- Tewkesbury Yearly Register, above, 15 June 1831; p. 58.

- England and Wales Criminal Registers 1791–1892, above NA, p. 273.

- The family came to the ironic attention of historian, the late Brian Linnell, in Tewkesbury Gossip, Theot Press, 1978, transcribed by Joan Smith, pp.53-4. “John Staite was the brother of Richard Staite … For a pickpocket and highwayman, he was given a very light sentence of 7 years. Edmund Staite made up the trio in 1832 with 14 years. Must have been quite a family reunion. Only a sister was missing; she was found not guilty of robbery.” [Editor]

- New South Wales, Australia, Convict Indents 1788–1842 database; State Archives NSW; Series: NRS 12188; Title: Bound manuscript indents, 1788–1842; Item: [4/4017]; Microfiche: 684.

- Convict Indents, above; Title: Annotated printed indents (i.e. office copies); Item: [X634]; Microfiche: 701.

- UK Prison Hulk registers and Letter Books, 1802–1849, NA, Microfilm, HO9/4 p. 219, 5 rolls.

- W. Branch Johnson, The English Prison Hulks (Phillimore, Sussex, 1970); on p. 32 he lists the clothing of the convicts as “suit of coarse slop clothing”.

- Charles Bateson, The Convict Ships 1787–1868, (A.H. & A.W. Reed Pty. Ltd., Frenchs Forest, 1974).

- NSW Registry of Births Deaths and Marriages, 1857/002165.

- C. Burd, Around Tewkesbury, 2001, p. 89.

Comments