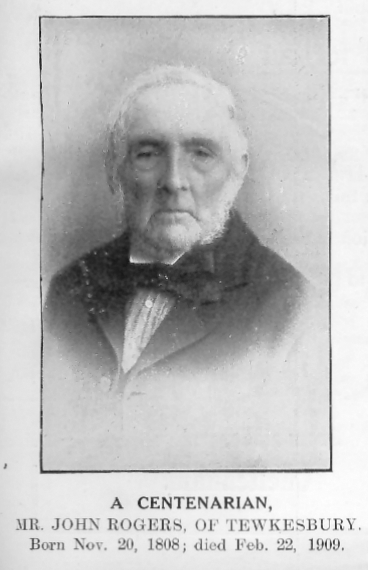

John Rogers (1808-1909)

Doing good without gold

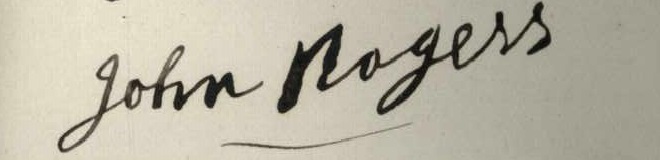

from the Tewkesbury MuseumClick Image

to Expand

John was born on 20 November 1808 in a house on High Street and was christened on Christmas Day in the abbey. His parents, Henry Rogers and Elizabeth nee Trueman had married there in 1802. John’s mother died when he was just two years old.

John received some education as a child in the town. He attended the Wesleyan Sunday School and the day school of a female Quaker teacher in Double Alley. When reflecting on his life, John said that at the age of eighteen he set about learning to read and write and then began to read a chapter of The Bible each day. His religious education set him up for a lifetime of Christian belief and good works.John was a whitesmith who learned his trade early in life working with his father who was a whitesmith and nail-maker. Newspaper reports tell us that John had learned two or three trades between the ages of 8 and 15 and learned how to manipulate a hammer as a young man. He was later apprenticed to Mr Churchill of Cheltenham as a whitesmith and a bell-hanger. John worked with Churchill for ten years by which time he wanted to be on the move, and he went to Oxford for a time.

John worked with the ironmonger Edward Brydges, earning £1 a week- a wage which rose by 24s within a week of working together. We can assume that John was good at his trade! Some of John’s work can still be seen in Tewkesbury and Cheltenham, including the ornate work around the Crimean War memorial which was unveiled in 1858.

In 1834 John married Worcester-born Harriet Stinton in Cheltenham. They married in Cheltenham Minster and settled in Tewkesbury. We know from reflections on John’s life that Harriet encouraged him to become a practising Baptist.

The couple and their growing family lived in Barton Street, then Wellington Cottage, off Chance Street, and finally settled at 66 Barton Street where John kept his whitesmith shop. His name can still be seen on the drain cover outside this property. John and Harriet had five children.

Although Tewkesbury was not an industrialised town, the way it had developed led to tightly packed housing which left it susceptible to waterborne disease and in 1832 there was a cholera outbreak. Seventy-six Tewkesbury residents died, of which a quarter were children under the age of 10. John Rogers busied himself visiting the sick, despite the risk to his own life in doing so.

John spent twenty-four years visiting the alms houses and the workhouse giving religious instruction. He was a regular weekly visitor at the workhouse and was well-known in the town for his observance of Christian beliefs. He was a bandleader at the alms houses at North-East terrace and also at nearby Pamington. As a Baptist he abstained from drinking alcohol for seventy years until his death.

John remarried two years after Harriet’s death in 1865; Sarah Potter, a spinster in her thirties and daughter of Isaac and Rebecca Potter of Tewkesbury. John and Sarah did not have any children together, but they lived and worked together until Sarah’s death in 1901, just 8 years before John’s death. The Potter family paid for their shared burial plot and gravestone.

We can assume that John saw both family happiness and unhappiness during his long years. The story which has endured through the records concerns the fate of seven of his grandchildren who lived in Cheltenham with his daughter and her husband Edward. Through a series of actions taken, probably because of poverty, John’s son in law found himself in prison at the age of thirty-six. He died two years after his release and Elizabeth died in extreme poverty two years later, leaving their seven children orphaned. John was involved in the re-homing of his grandchildren despite not having the money or space to accommodate them himself. The two eldest children were found roles in service. John wrote to Mr Müller who founded children's homes in Bristol and found places for two of the girls. Another grandchild went to the Cheltenham Female Orphanage where she would have been trained and then gone to work in service. One of John’s granddaughters went on to marry William Ernest Wathen, which is where John Rogers’ link with the bell ringers of Tewkesbury Abbey began.

Fewer people reached the grand old age of one hundred in the early 20th century than do today and the reports of John’s centenary were reported widely in the local and county newspapers and across the country. It is thanks to this great achievement of longevity that we know so much about him and others in his family.

On 20th November 1908 the bells of Tewkesbury Abbey were rung to honour John’s 100th birthday. It is likely that the Wathen family were ringing them!

John received a telegram from King Edward VII, the fifth monarch to reign during John’s long life. John also received a purse of gold coins from the town as well as congratulations from the Chancellor of the Exchequer (The Right Honourable H.H. Asquith, who was later Prime Minister) and the Lord Mayor of Bristol, Edward Robinson.

The Grand Old Man of Tewkesbury

The Grand old man of Tewkesbury is living with us still:

We never knew a better man in heart and mind and will.

‘Twas joy to hear the abbey bells proclaim the smiling morn,

That made it just a hundred years since this good man was born.

He is not blessed with riches, yet is liberal to the core

And in sickness or distress is always to the fore

A clever workman at his trade, he’ll leave his mark behind

Whist his kind feeling for the poor will keep him in our mind

He may yet live for many years; that we hope and pray;

And wish him gladness with old friends on this auspicious day.

Graphic of 22 February 1909

Sadly, in January of 1909 John fell in his bedroom. He broke his leg and had to remain in bed. He was reported to have lost consciousness on 19th February and died at 5.15pm on 22nd February. John’s daughter Harriet, his only surviving child, was with him when he passed away. It was reported that John had ‘lived a very beautiful life and died a very peaceful death’.

The report of John’s funeral in the local Tewkesbury newspaper tells us that his remains ‘were interred at Tewkesbury Cemetery amidst every manifestation of respect’. The chief mourners included his daughter Harriet and her husband, members of Sarah Potter’s family and Josiah Wathen, whose son had married John’s granddaughter. John’s gravesite can still be visited.

The service was conducted at the Baptist chapel in Tewkesbury and the Rev. W. Davies remarked “it is given to few to live for more than a century and we are especially grateful that our departed brother has left so quiet and yet so powerful a recommendation of the Christian faith and of the Divine Saviour of men’s lives”. Reference was made to John’s good works “In the church and in the alms houses and in the Sunday school and the workhouse it was his delight to give the message of good tidings of the grace of God; and the villages around, and once again in the town, where he had visited men stricken with cholera, all justified the saying that he did good without gold, and therein he proved himself to be a worthy example to the rank and file”.

During the hour of the funeral, mourning shutters were exhibited and blinds were drawn throughout the route of the cortege. The flag on the abbey tower was flown at half-mast and in the evening a muffled peal was rung.

‘His venerable and youthful figure, his brisk walk, his beautiful and refined face, his sweet and courteous manner, his wonderful sympathy, his humility, his appreciation of good in others, his consistent life, his kindness to the sick and poor, his prayers beside the bedside of the dying, are among those characteristics and virtues which his fellow townsmen will always associate with him. Mr Rogers would have left his mark behind him had he died twenty years ago, but he lived to the very end in full possession of all of his faculties of body, mind and heart. We have lost a friend, and an example which we could ill spare. May his influence still live on, though he is no longer here with us’.

Contributed by Sarah Smith, 4x great granddaughter (in law) of John Rogers.

Sources

We knew almost nothing about John Rogers until reading David Willavoys’ excellent article in the 2004 edition of the Tewkesbury Historical Society Bulletin.A small portrait of Tewkesbury’s Grand Old Man, used in this article, hangs in the Tewkesbury Museum on Barton Street. We believe this photograph was taken on his 100th birthday.

A copy of John Rogers’ letter to Mr Müller in Bristol was accessed through the archive team at mullers.org/orphanrecords and the story of his daughter’s family pieced together through those records, Cheltenham newspapers and online sources available through ancestry.co.uk.

Information about the Cholera outbreak in Tewkesbury is from the Tewkesbury Historical Society website.

All other information has been gleaned from editions of the Tewkesbury Register which is available online, along with census records.

Comments