The Jew of Tewkesbury. An Urban Myth?

Introduction

near his tomb in the AbbeyClick Image

to Expand

Among the many stories and tales told about Tewkesbury is a rather curious incident set in the 13th century. About the year 1260 a Jew of Tewkesbury is said to have fallen into a latrine on a Saturday and, not wishing to break the Jewish prohibition against working on the Sabbath, he refused to be pulled out. When Richard de Clare (1222-1262), 7th Earl of Gloucester, is said to have heard about the incident he would not permit the Jew to be pulled out on the Sunday, saying he should observe the Christian Sabbath with the same solemnity he had done his own. By the Monday we are told the Jew had died in filth and stench.

The question I wish to try to answer in this short paper is whether this event could really have happened, or is it perhaps one of Tewkesbury’s first urban myths?

Medieval Jewry

The Jews first arrived in England from Rouen in Normandy under William I some time after 1066. In Medieval Europe there was a need for credit within the economy; Christian Law, however, forbade usury (the lending of money with interest), but this law did not apply to Jews lending money to Christians. Therefore, with the Jews being restricted from other trades and not allowed to join the Guilds, they became the bankers of Medieval Europe. In England the Jews were quite literally the property of the King, and so heavy taxes (tallage) were levied on the Jews as a regular source of income. The first English cities to have a Jewry were London and Oxford; however, by the middle of the 12th century, they had settled in many provincial towns and cities. During this time, the Jews suffered a bitter history of exploitation and persecution. This includes the infamous massacre at York in 1190, as well as the ‘Blood Libel’ or false accusation that the Jews ritually murdered Christian children at Passover. One such ritual murder accusation occurred at Gloucester in 1168. With papal dispensations being issued to Italian bankers in the 13th century, the Jews had outlived their economic usefulness: in 1290 Edward I expelled the Jews from England. They were not officially to return until their readmission by Oliver Cromwell in 1656.“Ben’ son of Is’ of Tukeber’, Boneuye of Bedford, Peter son of Leo, Is’ of Campeden, Jews, mainperned [gave surety or bail] to have the body of Josceus son of Pygge, before etc. on the quindene [5th] of St. John the Baptist to answer the Abbot of Pershore touching the making of a certain false charter as it is said: and they had him not; therefore they are in mercy.

Isaac of Caumpeden, Meyr of Bruges and Ben’ son of Is’ of Teukesbery, who mainperned [gave surety or bail] Simon son of Salamon, to have his body before etc. on the octave [8th] of St. John the Baptist, to answer touching coin-clipping of which he was accused, have him not; therefore they are in mercy. And the Sheriff is ordered to take them under safe etc. so that he have their bodies before etc. on the quindene [5th] of St Michael etc.

The Sheriff was ordered to take all Jews and Jewesses abiding without the community etc. and in a town where no chyrograph chest exists, and take all their chattels into the King’s hand, so that he should have the bodies of them, their wives and children, together with said chattels before etc. on the octave [8th] of St. John the Baptist to answer touching this that they abide against the statute etc. and the Sheriff has sent word that Belia of Bretstrete abides at Bretstrete [Gloucester] and Vives son of Belia abides in the same place; and that Ben’ son of Is’ of Honyton abides at Teukesbery; but he has them not nor the value of the chattels, nor has he done ought theron. Therefore he, towit Adam Le Botyler, is in mercy. And he is ordered sicut alias [as previously] for the morrow of St. Margaret. On which day the Sheriff has sent no word theron nor returned the writ. Therefore sicut alias [as previously] for the quindene [5th] of St. Michael etc.”

The first two records relate to accusations of making a false charter and coin clipping, which were common charges levelled against the Jews. Here Benedict/Benjamin gives surety that the two accused will appear to hear the charges, but on neither occasion does this actually happen. However, the third record is of more direct relevance to the Tewkesbury community. In 1253 Henry III had restricted the Jews to living only in recognised communities with a chirograph chest to hold the legal records of Jewish loans, which did not include Tewkesbury. In 1277 the sheriffs in each county were ordered to bring before the Justices those Jews who were living outside of these recognised communities. Adam Le Botyler sheriff of Gloucester reported that Ben’, son of Isaac of Honiton, was living at Tewkesbury, but took no further action against him.[6]

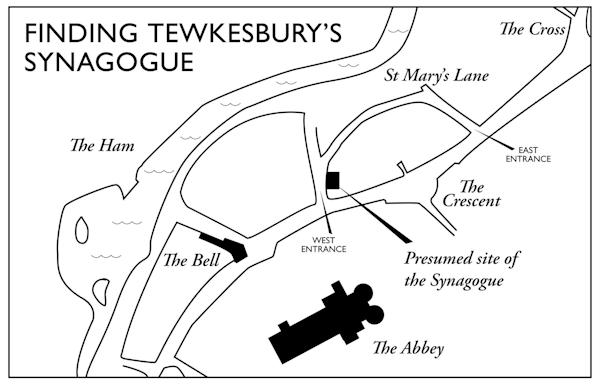

As for the actual location of the Jewry, all that exists is a rather late reference found in John Leland’s Itinerary of 1535-1543. When quoting from the Antiquitate Theokesbiriensis Monasterii about the hermit Theoc after whom Tewkesbury was supposedly named –"Theoc the hermit held a house near the Severn from whence Tewkesbury" – he adds “Sum say that Theocus Chapelle was aboute the place wher syns the Jues Synagoge was”. Unfortunately Leland does not tell us where in the town the synagogue was said to have been located. Nevertheless, James Bennett in his History of Tewkesbury records a local tradition that the synagogue was situated in St Mary’s Lane:[8]

“Some remains of an ancient stone building exist near the entrance to St Mary’s Lane, but there is no record or tradition to guide us in ascertaining when or for what purpose it was erected. The portions of the fabric which are now discernible would lead to the conclusion that it was designed for a place of religious worship; and hence some have conjectured that it was the chapel of Theocus… Some persons imagine it to be the remains of the Jew’s synagogue, but that is by no means probable.”

St. Mary’s Lane (see figure 2) forms an east-west crescent on the north side of Church Street, onto which it has two entrances. The eastern entrance to St. Mary’s Lane (nearest the cross), though widened from its original medieval width, has 15th to 16th century timber framed buildings on either side, none of which match Bennett’s description in 1830. However, the western entrance to St. Mary’s Lane (nearest the abbey) has evidence of timber framed buildings on only one side, the other side (67 Church Street) being occupied by a late 18th century brick building with a mid 19th century extension to the rear (see figure 3, far left). This brick extension seems the most likely location for the ancient stone building described by Bennett in 1830, although he was sceptical about the remains having been a synagogue.

Go to this article for an update on this section and more information about 89-90 Church Street

Chronicles

From the early 14th century onwards the alleged incident concerning the ‘Jew of Tewkesbury’ is repeated almost verbatim in a number of Latin chronicles. The earliest of these accounts appears to be the chronicle of William Rishanger (c.1250-c.1312) composed at St. Albans Abbey, but interestingly makes no mention of Richard de Clare. However, the most widespread account was that included in the Polychronicon by the Chester monk Ranulph Higden (died 1365), of which there are two Middle English translations by John Trevisa (1326-1412) and an unknown 15th century writer: [11]

“Urbanus quartus post Alexandrum sedit papa annis fere quatuor [1261–1264]… Circa illud tempus apud Teoksbury quaidam Judæus per diem Sabbati cecidit in latrinam, nec permisit se extrahi ob reverentiam sui Sabbati. Sed Ricardus de Clara comes Gloverniæ non permisit eum extrahi die Dominica ob reverentiam sui Sabbati et sic mortus est.

After Alexander þe ferþe Urban was pope nygh foure 3ere [1261–1264]… Aboute þat tyme at Teukesbury a Jewe fel into a gonge in a Satirday, and wolde suffre no man drawe hym up for reverence of his holy day. But Richard of Clare, erle of Gloucestre, wolde suffre no man drawe hym up on þe morwe in þe Sonday for reverence of his holy day, and so þe Jewe was dede.

Urban iiij succedit pope Alexander allemost iiij yere [1261–1264]… Abowte this tyme a Jewe felle into a sege at Theokesbury on theire sabbathe day, and wolde not suffre to be drawen from the sege in that day for reverence of theire sabbat. And Richard of Clare, erle of Glowcestre, beynge þer þat tyme, and understondynge and knowynge of that Jewe, wolde not suffre hym to be taken furthe on Sonneday for reverence of his sabbat, and so the Jewe diede in the sege.”

In Thomas de Burton’s (1396) Chronica Monasterii de Melsa, Higden’s Latin account of the story is repeated twice, but with no additional information.[12] The story is subsequently found in a number of 16th century references, with the ‘Jewe at Tewxbery’ also mentioned in John Leland’s Itinerary of 1535-1543.[13] These references include Robert Fabyan’s The New Chronicles of England and of France (1516), John Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (1570) and John Stow’s A Survey of London (1598):

“In this yere also [1259] fell that happe of the Iewe of Tewkysbury, which fell into a gonge vpon the Satyrday, and wolde not for reuerence of his sabot day be pluckyd out; whereof heryng the erle of Gloucetyr that the Iewe dyd so great reuerence to his sabbot daye, thought he wolde doo as moche vnto his holy day, which was Sonday, and so kepte hym there tyll Monday, at whiche season he was foundyn dede.” [14]

“And for so much as mencion here is made of the Iewes, I cannot omit what some English stories write of a certain Iew: A Iewe fallen into a priuey would not be taken out for kepyng hys sabboth day. who not long after this tyme aboute the yeare of oure Lord. 1257. fell into a priuy at Tewkesbury vpon a sabboth day, which for the great reuerence he had to his holy sabboth, would not suffer him selfe to be plucked out. And so Lord Richard Earle of Glocester, hearing therof, would not suffer him to be drawue out on Sundaye for reuerence of the holy day. And thus the wretched superstitious Iewe remayning there tyll mondaye, was found dead in the doung,” [15]

“The 43rd [regal year of Henry III], a lewe at Tewkesbery fell into a Priuie on the Saturday and would not that day bee taken out for reuerence of his sabboth, wherefore Richard Clare Earle of Glocester kepte him there till munday that he was dead.” [16]

From as early as the 13th century, analogous stories had been circulating in both France and Germany. By the 17th century, the story would seem to have been known more widely in Europe, with ‘Solomon the Jew of England’ appearing in the Jesuit author Jacob Masen’s (1606-1681) Familiarium Argutiarum Fontes.[18] Similar stories are recorded throughout Germany[19] and Prussia, where it was assimilated into native folklore, often as an event said to have occurred locally. An example of this would be ‘The Imprisoned Jew at Magdeburg’ which first appears in 1563 in Hans Kirchhof’s Wendenmuth[21]. A 19th century version of the story[22] has been translated from German as follows:[23]

“At the time of Bishop Conrad of Magdeburg, who was born a Count of Sternberg, and who died in the year 1278, a Jew fell into a privy on a Saturday. Because it was the Sabbath, the Jews would not pull him out, nor would they allow Christians to do so, because the Jew would have had to help by grabbing hold with his hands. The Bishop was so outraged by this superstition that the following day, Sunday - the Christian Sabbath, he decreed that the Jews would have to keep the Christian Sabbath as well. Thus the poor fool had to spend two days and two nights stuck in a privy.”

Verse

As well as the above narratives, it appears that a verse account of the dialogue between Solomon and Richard de Clare was circulating from at least the 14th century onwards. In the margin of Higden’s Polychronicon[14] is the following short Latin verse written in a medieval hand:

“Dum purgat ventrem, Salmon Judæus olentem; In foveam cecidit, ‘Hodie non absrahar’ inquit; Refertur comiti, Comes subridet et inquit; ‘Sabbata nostra quidem, Salmon servabit ibidem’.”

“While purging his belly, Solomon the smelly Jew; Into the pit he fell, ‘On this day do not pull me out’ said he; When reported to the council, the Earl smiled and said; ‘Our Sabbath indeed, Solomon will observe in the same place’.”

The first and last lines of the verse are written in Leonine metre, which rhymes at the middle and end of each line (shown in bold). In another version of the Polychronicon[25] a two-line verse is recorded, which again conforms to the same metre. This two-line verse was then expanded to three lines in an Evesham chroniclecompiled about 1392 from earlier texts.[26] In Robert Vilvain’s Enchiridium Epigrammatum Latino-Anglicum (1654) an almost identical ‘Dialog betwixt a Christian and a Jew which fell into a Jakes at Tewkesbury’ is repeated, along with an English translation:[27]

“Tende manus Salomon, ego te de stercore tollam; Sabbata nostra colo, de stercore surgere nolo; Sabbata nostra quidem, Salomon celebrabis ibidem.”

“Jew, reach thy hand to me, from the draugh I will thee free; Our Sabbaths I observ, and wil here rather sterv; Then Jew sans more adoo, ther keep our Lords day too.”

It is this final version of the Latin verse that is printed in many 19th century references,[28] including Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable.[29]

Origins

What may be the earliest account of the story was first discussed by Rev. W.D. Macray in Gloucestershire Notes and Queries[30], but makes no mention of either Tewkesbury or Richard, Earl of Gloucester. It appears in a collection of French-Latin verses dating to about 1180: [31]

“De quodam Judæo: Dum de latrinæ lapsu Salomona (na sa Samsona) ruina; Extraherent laqueis, ‘Non trahar’ inquit eis; ‘Sabbata sunt’ plaudit populus, plausum Comes (Tibald) audit; Audit, et ipse jubet cras ut ibi recubet.”

“Of a certain Jew: While at the latrine Solomon (if not Samson) slipped and fell down; They pulled up a noose, ‘Do not pull’ said he; ‘It is the Sabbath’ the people applauded, applause the Count (Theobald) heard; Heard, and he ordered that tomorrow there he would remain.”

The manuscript also contains other 12th century verses attributed to Serlo of Paris and Hildebert of Tours.[32] The verse has two interlinear notes (in brackets above) added in same hand as main text; therefore, they appear to be broadly contemporary. Above the word ‘comes’ (count or earl) we find the name Tibald (Theobald) added. Macray suggests that he was probably a Norman count and perhaps even Theobald V of Blois who in 1171 burnt many Jews on the ‘blood libel’ charge of crucifying a Christian child. Nevertheless, Macray goes on to say that it is difficult to account for the repetition of the story if there were no basis at all for the Tewkesbury version. However, it seems unlikely that almost identical incidents could have occurred in both 12th century France and 13th century Tewkesbury: both occasions involving a Jew named Solomon and a count or earl. As we have seen in Germany and Prussia, where the story was assimilated into local folklore, the same process could have occurred earlier in Tewkesbury, leading to the adoption this medieval ‘urban myth’.

If the underlying story of the Jew falling into a cess-pit on the Sabbath and refusing to be pulled out is a myth, what could have inspired it? The story seems to draw on two main anti-Semitic or anti-Judaic themes.[33] Firstly, in the medieval Christian world-view, there was a clear division between those who were considered pure and those who were considered impure. The Jew of Tewkesbury is to be found in a pit full of excrement, clearly suggesting he belongs with the impure. Another example of this correlation between the Jews and the ‘impure’ privy/latrine would be the alleged ritual murder of Adam of Bristol (1183), whose Jewish abductor Samuel was said to have crucified the boy in his privy.[34] This same theme also appears in Geoffrey Chaucer’s Prioress’ Tale,[35] where a Jew cuts the throat of a young Christian boy and throws the body into a pit “where these Jews purge their entrails”:

“This cursed jew hym hente, and heeld hym faste; And kitte his throute, and in a pit hym caste. I seye that in a wardrobe they hym threwe; Where as thise jewes purgen hire entraille.”

Secondly, in this world-view it is the Jew of Tewkesbury’s dogmatic following of the letter of the law, which ultimately results in his own death. This view of Jewish law mirrors disputes between Jesus and the Pharisees found in the Gospels, particularly those relating to Jewish observance of the Sabbath: [36]

“Et ecce homo manum habens aridam et interrogabant eum dicentes si licet sabbatis curare ut accusarent eum. Ipse autem dixit illis quis erit ex vobis homo qui habeat ovem unam et si ceciderit haec sabbatis in foveam nonne tenebit et levabit eam. Quanto magis melior est homo ove itaque licet sabbatis benefacere. Tunc ait homini extende manum tuam et extendit et restituta est sanitati sicut altera.”[37]

“And, behold, there was a man which had his hand withered. And they asked him [Jesus], saying, Is it lawful to heal on the sabbath days? that they might accuse him. And he said unto them, What man shall there be among you, that shall have one sheep, and if it fall into a pit on the sabbath day, will he not lay hold on it, and lift it out? How much then is a man better than a sheep? Wherefore it is lawful to do well on the sabbath days. Then saith he to the man, Stretch forth thine hand. And he stretched it forth; and it was restored whole, like as the other.” [38]

Furthermore, the subject matter in the above passage appears to be an obvious source for the Jew of Tewkesbury story. But perhaps more significantly, in the Latin Vulgate Bible some of the wording (shown in bold) is strikingly similar to that found in the various medieval verses already discussed.

Jewish Law

The underlying assumption in the story of the Jew of Tewkesbury is that he had refused to be pulled from the privy to avoid working on the Sabbath and, thereby, comply with Jewish law. However, we need to consider whether this is a true reflection of Jewish teachings, or a Christian interpretation derived from the Gospels.

In fact virtually all of Jewish laws can be set aside, in order to avoid serious injury or to save a human life. The obligation to save a life (Pikuach Nefesh) is based on the commandment “Thou shalt not stand idly by the blood of thy neighbour”.[40] In the 3rd to 5th centuries A.D. the Talmudic rabbis ruled that the preservation of human life takes precedence over all the other commandments, except for the prohibitions against murder, idolatry and incest.[41] Furthermore, when considering the commandment “Ye shall therefore keep my statutes and my judgements, which if a man do he shall live in them”[42] the rabbis added “he shall live by them, but not die by them”.[43] This same principle also applies to the Sabbath laws, which may be suspended to safeguard the health or life of the individual. For example it is permitted to light a fire on the Sabbath to keep an ill person warm, or extinguish a light to help them sleep.

The Jewish Sabbath lasts from sundown on a Friday evening until sundown on the following day. If the Jew of Tewkesbury had fallen into a privy on a Saturday, the question is whether he or his community would have considered his life to be in danger. Whilst his situation may have been extremely unpleasant, did he simply have to wait until sundown to be pulled from the pit? Or would the community have known about the dangers from disease or infection, and so been obliged by Jewish law to pull him from the pit? In the 13th century knowledge of how diseases were transmitted was somewhat limited. Nevertheless, the Talmudic Rabbis regarded the maintenance of good health as a religious duty. The importance of hygiene in preventing illness was keenly understood, with an emphasis being placed upon bodily cleanliness.[44] Furthermore, the great Jewish philosopher and physician Moses Maimonides (1135-1204) wrote about the need for good hygiene and sanitation in avoiding disease. Maimonides wrote a total of ten medical works of which the sixth (Treatise on Asthma) recommended that toilets should be built as far away from dwellings as possible.[45]

Conclusions

The Jew of Tewkesbury is a fascinating, and yet horrifying story, which draws us back into the medieval Catholic world. A world in which the Jew’s predicament (trapped in a privy), and subsequent death, is found both amusing and thought to be his rightful punishment. Now, after centuries of persecution culminating in the Nazi genocide of European Jewry, such stories are an uncomfortable reminder as to the roots of this prejudice. But, could this event really have happened, or is it yet another anti-Semitic myth, which like the ‘blood libel’ has its origins in medieval England?

The fact that Jews were living in 13th century Tewkesbury is not in question. However, the actual location of the Jewry is less certain. Whilst local tradition suggests that a synagogue was located in St. Mary’s Lane, this is not supported by any documentary evidence.

The earliest account of a Jew falling into a latrine on the Sabbath and refusing to be pulled out would appear to have been written in France during the 12th century. It, therefore, seems highly unlikely that an almost identical incident could have occurred a century later in Tewkesbury, both occasions involving a Jew named Solomon and a count or earl (Latin comes). Furthermore, the first version of the story to locate the incident in Tewkesbury[46] makes no mention of Richard de Clare the Earl of Gloucester. As in 16th century Germany, where the story was assimilated into local folklore with the ‘Jew of Tewkesbury’ becoming the ‘Jew of Magdeburg’, so too in the 12th-13th century could the scene of this French story have been relocated to Tewkesbury?

The underlying story draws on two main anti-Semitic or anti-Judaic themes. Firstly, the obvious correlation that is drawn between the ‘impure’ Jew and the latrine in which he is standing. Secondly, the suggestion that it is the Jew’s own dogmatic following of religious law that leads to his death. Here the story appears to match far too closely the parable of the sheep falling into a pit on the Sabbath, and the subsequent disagreement between Jesus and the Pharisees about breaking the Sabbath in order to save a human life.[47] However, this is not a true reflection of Jewish teaching, and it may surprise many to learn that both Jesus and the later Talmudic Rabbis were broadly in agreement on this issue. In fact the Talmud argues that the Sabbath can and should be broken in order to save someone’s life.[48] Furthermore, the Talmud[49] and Jewish scholars like Maimonides clearly recognised the link between good hygiene and sanitation in avoiding often fatal diseases.

Notwithstanding the above possible sources of the story, could such an incident really have happened? At times people must have fallen into privies or latrines, including Jews, whether in medieval France, England or Germany. However, Jewish teaching suggests that the dangers from such a situation would have been clearly understood, and that no individual would have been left in this predicament, even on the Sabbath. Therefore, along with the apocryphal hermit ‘Theoc’ after whom Tewkesbury was supposedly named, the ‘Jew of Tewkesbury’ would appear to be yet another one of the town’s medieval ‘urban myths’.

I would like to thank Pat Roberts for suggesting the use of ‘urban myth’ in the title, Steve Goodchild for pointing out the references in Gloucestershire Notes and Queries, Joe Hillaby for providing the Exchequer of the Jews references, Bruce Watson for providing the reference in John Stow’s A Survey of London, and Anthony Bale for allowing me to see extracts from his forthcoming book on medieval English anti-Semitism.

BIOGRAPHYRichard Sermon is a graduate of Southampton University and has lived in Tewkesbury since 1994. He was formerly Gloucester City Archaeologist, but has recently been appointed Archaeological Officer for Bath and North East Somerset. In 1982-3 he studied both modern and biblical Hebrew in Israel, and since then has developed an interest in Anglo-Jewish medieval history and archaeology. In 1990 whilst working for the Museum of London he reinterpreted the Gresham Street Mikveh (Jewish Ritual Bath), which at the time was thought to have been a strong room.[50] More recently he has collaborated with Joe Hillaby (Bristol University) and Bruce Watson (Museum of London) on the Milk Street Mikveh discovered in 2001,[51] and a reinterpretation of Jacob’s Well in Bristol as a Bet Tohorah, or house for washing the dead before burial.[52]

References

- Skinner P. ed. 2003, Jews in Medieval Britain: Historical, Literary and Archaeological Perspectives, London.

- Hillaby J. 1994, The Ritual Murder Accusation and Harold of Gloucester, Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England 34, 74-81.

- Hillaby J. 1984, The Jewish Community at Hereford 1179-1253, Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists Field Club 44, 358-419; Hillaby J. 1987, The Clients of the Jewish Community at Hereford 1179-1253, Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists Field Club 45, 192-270; Hillaby J. 1990, The Last Decades of Hereford Jewry 1253-90, Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists Field Club 46, 432-487; Hillaby J. 1990, The Worcester Jewry 1158-1290, Transactions of the Worcestershire Archaeological Society 3, Series 12, 73-122; Hillaby J. 2002, The Gloucester Jewry and its Neighbours 1159–1290, Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England 37, 41–112.

- Hillaby, 2002 109-10.

- Jenkinson H. ed. 1929, Calendar of the Plea Rolls of the Exchequer of the Jews, London, III, 294 and 319.

- Hillaby, 2002, 109-10.

- Toulmin Smith L. ed. 1909-1910, The Itinerary of John Leland, London, IV, 150.

- Bennett J. 1830, The History of Tewkesbury, London, 241-2.

- Blacker B.H. ed. 1881, Gloucestershire Notes and Queries, London, I, 264-5.

- Blacker, 1881, 307.

- Rawson Lumby J. ed. 1882, Polychronicon Ranulph Higden, Rolls Series, VIII, 246-7.

- Bond E.A. ed. 1867, Chronica Monasterii de Melsa, Rolls Series, II, 134 and 137.

- Toulmin Smith, 1910, V, 93.

- Ellis H. ed. 1811, Robert Fabyan, The New Chronicles of England and of France, London.

- Foxe J. 1570, Book of Martyrs, London, IV, 410.

- Kingsford C.L., ed. 1971, John Stow, A Survey of London, I, Oxford, 280.

- Bale A. 2001, Locating the Jew of Tewkesbury, Mediaevalia 20, 19-47.

- Masen J. 1711, Familiarium Argutiarum Fontes, Cologne, 260-1.

- Blacker, 1881, 306.

- Grässe J.G.T. 1868, Sagenbuch des Preußischen Staats, Glogau, I, No 277, 229-230.

- Österley H. ed. 1869, Hans Wilhelm Kirchhof, Wendenmuth, Tübingen, I, 483.

- Temme J.D.H. 1839, Die Volkssagen der Altmark, mit einem Anhange von Sagen aus den übrigen Marken und aus dem Magdeburgischen, Berlin, 133.

- Ashliman D.L. ed. 2001, Anti-Semitic Legends, Pittsburgh University.

- Rawson Lumby, 1882, 246-7.

- Rawson, MS B.

- Bodleian Library, MS Laud 529 folio 56b; Blacker, 1881, 265.

- Vilvain R. ed. 1654, Enchiridium Epigrammatum Latino-Anglicum, London, Epigram 39.

- Bennett, 1830, 241; Blacker, 1881, 461-2.

- Brewer E.C. ed. 1894, Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, London, 744.

- Blacker, 1881, 307.

- Bodleian Library, MS Digby 53, folio 15.

- Hildebert of Lavardin, c.1056-11

- Achinstein S. 2001, John Foxe and the Jews, Renaissance Quarterly, 54.1, 86-120; Bale 2001.

- Adler M. 1939, Jews of medieval England, London, 185-6.

- Cawley A.C. ed. 1996, Geoffrey Chaucer, Canterbury Tales, Everyman, 570-3.

- Matthew 12:10-13 and Luke 14:2-5.

- Latin Vulgate Bible, Matthew 12:10-13.

- King James Bible, Matthew 12:10-13.

- Exodus 20:8-10 and 31:14-15.

- Leviticus 19:16.

- Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 74a.

- Leviticus 18:5.

- Babylonian Talmud, Yoma 85b.

- Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 108b.

- Rosner F. 2002, The Life of Maimonides, a Prominent Medieval Physician, Einstein Journal of Biology and Medicine 19, 125-8.

- Rishanger’s Chronicle, Blacker, 1881, 307.

- Matthew 12:10-13.

- Babylonian Talmud, Sanhedrin 74a and Yoma 85b.

- Babylonian Talmud, Shabbat 108b

- Sermon R. 1990, The Guildhall House Strong Room or Ritual Bath?, Department of Urban Archaeology Newsletter, September, 12-14.

- Blair I., Hillaby J., Howell I., Sermon R. and Watson B., 2002, The discovery of two medieval mikva’ot in London, Transactions of the Jewish Historical Society of England 37, 15-40; idem, 2001, Two medieval Jewish ritual baths, mikva’ot, found at Gresham Street and Milk Street in London, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeoogical. Society 52, 127-37; idem, 2004, The Milk Street Mikveh, Current Archaeology 190, 456-61.

- Hillaby J. and Sermon R. 2004, Jacob’s Well, Bristol: Mikveh or Bet Tohorah?, Transactions of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 122, 127-151.

Comments