The Continuing Mystery of William Sandilands

Introduction

West, Heath and Farrington

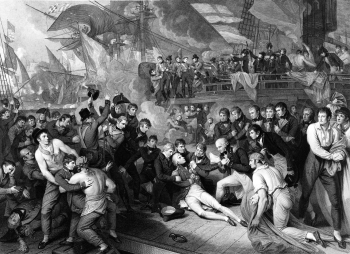

The death of Nelson, arguably Britain’s first National Press ‘hero’, ensured that the news of a naval victory on a par with the defeat of the ‘Spanish Armada’ was elevated to an unparalleled outpouring of national grief. In an age when ‘neo-classicism’ of thought, learning, art and architecture was a national obsession, he was transformed from a hero almost to a deity.

It was not surprising, then, that a large number of ‘heroic’ paintings of Nelson’s death were embarked upon by foremost artists of the day. One of the first of these ‘on the scene’ was Benjamin West (1738-1820), an American ‘Neo-Classicist’ who became naturalised during the final years of the eighteenth century and was co-founder and Chairman of the Royal Academy. In 1771, he had painted one of the most famous ‘epic’ scenes of the day – The Death of Wolfe. General Wolfe, like Nelson, had died at the moment of victory.[1] A decade after Nelson’s death, a story was told of a meeting between the admiral and the artist, during an entertainment given by Sir William Hamilton that was purported to have taken place immediately before Nelson sailed for Trafalgar. Nelson had exclaimed to his host and West:

“... ‘there is one painting whose power I do feel. I never pass a printshop where your ‘Death of Wolfe’ is in the window, without being stopped by it’. West, of course, made his acknowledgments, and Nelson went on to ask why he had painted no more like it. ‘Because, my Lord, there are no more subjects.’ ‘D--n it,’ said the sailor, ‘I didn’t think of that,’ and asked him to take a glass of champagne. ‘But, my lord, I fear your intrepidity will yet furnish me such another scene; and, if it should, I shall certainly avail myself of it.’ ‘Will you?’ said Nelson, pouring out bumpers, and touching his glass violently against West’s, – ‘will you, Mr. West? then I hope that I shall die in the next battle.’ He sailed a few days after...” [2]

West was visited by one Joseph Farrington on 29 November 1805, not three weeks after the news of Nelson’s death had broken in the Times. Farrington recorded in his diary that West had decided to resign from the Chairmanship of the Royal Academy, partly in order to make time to embark upon a painting, which was to be entitled The Death of Nelson.[3] West was then to go into partnership with an engraver, James Heath, who would subsequently produce an engraving of the finished work – the proceeds of the prints being sold on the open market to raise money to cover the artist’s expenses.

It should be noted that Joseph Farrington (1741-1821), a landscape painter of the 18th Century ‘Romantic’ school, wrote diaries over the course of twenty years that were published after his death. Farrington was, like West, a senior figure in the Royal Academy and his entries record much of what is known of the lives and dealings of many prominent figures in the Art world of the Regency. Farrington’s daily musings reveal him as someone much interested in the affairs, and often misfortunes, of others.

Farrington visited West again at his studio on 16 March 1806 and discovered that West had made rapid progress: “It was all painted in & would employ him a month more to harmonise and give effect to it.” [4]

'The Death of Nelson'

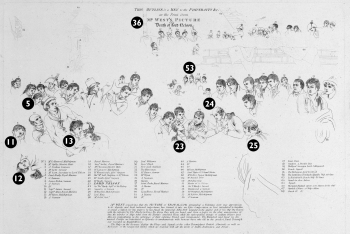

The painting was completed in May 1806. Within two months, West had issued 6,500 admittance cards, and estimated that thirty-thousand people had viewed the work in his studio.[6] Significantly, the names of those portrayed are recorded: when Heath completed his engraving of the picture five years later (the engraving was a best-seller), a line-work Key to the names was also issued. William Saunders is portrayed kneeling in front of Nelson, and laying a captured Spanish flag (popularly believed to have come from the monstrous Santissima Trinidad at the Admiral’s feet.

What does this mean? What has to be realised is that the painting is NOT an accurate representation of Nelson’s death. Firstly, West knew that Nelson actually died in the hold of the Victory, not on the quarterdeck. However, West said that Nelson, the ‘Hero’, “should not be represented dying in the gloomy hold of a ship, like a sick man in a Prison Hole.”[7] Secondly, the work portrays, simultaneously, a number of incidents that happened on the Victory’s quarter-deck over the course of the battle: the death of Scott, Nelson’s secretary, which happened an hour beforehand; the wounding of Midshipman Rivers, which took place a few minutes beforehand; and the death of Captain Adair, the Marine officer, fifteen minutes after Nelson was carried down. We see Captain Hardy reading from a list of captured French and Spanish ships: that news was in fact conveyed verbally three hours after Nelson’s wounding. Finally, there is the fictitious presentation by Saunders of the Spanish flag.

“Saunders, a Seaman, who is represented in West’s picture of the Death of Lord Nelson, kneeling before His Lordship, came in, and I conversed with Him abt. the action. He treated as ridiculous what Lucas the French Captain said to Bonaparte of His having silenced the firing of the Victory. – He said He never saw Lord Nelson after He was wounded for He was carried below immediately. – West has made a picture of what might have been, not of the circumstances as they happened.” [8]

Undoubtedly, Saunders had been in the thick of the battle. He would have known that the main guns of the Victory ceased firing at Captain Lucas’s ship Redoutable as both vessels were locked together by their spars and a fire on one would have spread to the other.[9] However, what is most revealing for us is Saunders’ reported comment. He may have accused Lucas of boasting of having seen the stricken Nelson. The event itself was unlikely, given that the quarterdeck of Redoutable was lower than that of the Victory. Otherwise, it suggests that Saunders did not carry Nelson down to the cockpit!

Old Men's Memories

If Farrington reported ‘Saunders’ correctly, then one must doubt old man Sandilands’ account of his part in the action. This leads to the question – was Sandilands just an old rogue who had managed to fool everyone right up to the officials of Queen Victoria herself? (This is yet another mystery!) Did his presence in a painting by one of the greatest artists of the day change the facts in the old tar’s mind into greater feats of imagination? We may never know.

Nelson’s demise continued to reverberate in the art world. The Irish painter, Daniel Maclise, created another epic death scene, entitled The Death of Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar, between 1859 and 1864. This resides in the Houses of Parliament. To achieve accuracy, he borrowed Nelson’s uniform and medals, measured the distances between the guns on Victory’s quarterdeck and amassed a collection of relics of the battle. Like Benjamin West, he interviewed survivors from the battle, who included Robert Drummond, a servant of Nelson, who himself had appeared in West’s picture. As one reviewer stated, Maclise had “set about his subject with a determination to master its details in a manner to challenge the greeting of naval connoisseurs, who, in all things professional are nothing if not critical...”.[11] When the work was completed, “veteran officers would still stand before the painting and contradict each other as to the details...”.[12]

In retrospect, it is difficult to understand why, if the claim of Sandilands that he had carried Nelson was indeed fraudulent, it went totally unchallenged in the press. Currently, this author is examining a number of other sources that may yet cast more light upon the subject. If more is discovered, it will be revealed in the next Bulletin.

Acknowledgements & References

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS:

Doug McCarthy, National Maritime Museum (Picture Library); Alex Kidson, The Walker Gallery, Liverpool; Jonathan Roper, NATCECT Library, University of Sheffield; The Librarian, Trinity College Dublin; The British Library; Birmingham Central Library.

REFERENCES:

1. Wolfe’s men had, in 1759, captured the impregnable fortress-town of Quebec from the French after scaling a sheer cliff known as the ‘Heights of Abraham’.

2. George S. Hilliard, (ed.,) Life Letters and Journals of George Ticknor, (Boston, 1876), Vol. I, p63, quoted in Helmut von Erffa and Allen Staley, The Paintings of Benjamin West, (Yale University Press, New Haven & London 1986). The date of this conversation is uncertain, as Hamilton had died in 1803.

3. Kathryn Cave (ed.), The Diary of Joseph Farrington, (Yale University Press, New Haven and London, 1982), Vol. VII (Jan 1805-June 1805), Vol. VIII (July 1806-Dec 1807).

4. Cave, above.

5. Letter from West to Watkins Trench, 17 Feb 1806 (Historical Society of Pennsylvania), quoted by von Erffa and Staley, as above.

6. Cave: Farrington Diary, 11 May and 2 July 1806. West’s painting now resides at the Walker Gallery, Liverpool.

7. Cave: Farrington Diary, 1 June 1807. In fact, another artist, Arthur William Devis, sketched officers present at Nelson’s death and portrayed the event in the cockpit. West followed suit with his own ‘gloomy hold’ painting in 1808.ave: Farrington Diary, 8 July 1806. The first mention of Saunders in connection with West’s painting was in La Belle Assemblée, 1 May 1806.

8. Captain Lucas of the Redoutable was admired by the British as a gallant and fearless opponent: he had been invited to Nelson’s funeral and in April 1806 released on Parole from house arrest in Reading. Upon his subsequent return to France, Napoleon had awarded him Captain of Legion of Honour. A report by Captain Lucas appeared in the Times, 30 December 1805; further details appeared in the Times, 14 May 1806.

9. John D. Clarke, The Men of H.M.S. Victory at Trafalgar, (Vintage Naval Library, 1999). The three who achieved high rank were: Boy 1st Class Henry Lancaster, a vicar’s son, who later rose to the rank of Commander and died in Connaught Square, London, in 1862; Midshipman John Lyons was a retired Admiral by the time of his death in 1872; Midshipman John Pollard, a retired Commander in 1864, having received Greenwich Hospital pension for 9 years, lived until 1868.

10. Art Journal, 1 September 1863, quoted in Nancy Weston, Daniel Maclise: Irish Artist in Victorian London (Portland Press, London and Oregon, USA, 2001).

11. Weston, above.

12. Weston, above.

Comments