The Cinema in Tewkesbury

Episode 1 On the road

Cheltenham Graphic (Gloucestershire Archives)Click Image

to Expand

Diamond Jubilee Year, 18 September 1897, just one year after the first public showing of animated pictures in England, and the jerky figures of Bob Fitzsimmonds and Gentleman Jim Corbett flickered across the screen before a fascinated audience of Tewkesbury circus-goers. It may not have been the first time any of them had seen the ‘movies’, but it was the first time in Tewkesbury. The film came with one of the sideshows with Fred Ginnett’s Royal Circus, which might have been the source of MGM’s roaring lion – or perhaps not. For the next twenty years films shown locally came in a variety of packages as part of fairs and circuses, usually bolstered by live acts between screenings.

These cinemas travelled complete. Films, projector, screen, seating and hall, this last usually a large tent, moved along the roads just like all the other circus shows. However, the mobile cinema often made use of existing accommodation, such as the local music hall or Town Hall. West’s Animated Pictures were frequently on the bill of the Philharmonic Hall between 1902 and 1907. Silvograph Animated Pictures enjoyed a brief popularity in 1901 and Century Animated Pictures in 1904. There may have been others, but none so well known.

One of the ‘all-in’ showmen was Fred Boulton. His ‘Pavilion’ – a large marquee – dominated Wyatt’s Meadow for several weeks from 11 July 1910. His shows were different in that he stayed put and altered his programmes every few days, a significant step forward from moving the same film from town to town. In this case there seems to have been some trouble on opening night, as the following day he made public apology for the mistakes of his operator who ‘did not understand limelight’, and advising that a more experienced operator had been hired from London.

Cinema in WWI

[R Wherrett,-Ebay]Click Image

to Expand

‘The Palace’ closed for a few weeks in 1914 to re-open as ‘Shakespeare Shenton’s Picture Palace Playhouse’. It showed films only. By a coincidence the sole attendant was Cecil Bennett, whose namesake was to be manager fifty years later.

Mr. Shenton’s licence was renewed annually throughout the war years, the only competition coming from travelling propaganda films, of which there were a surprisingly large number. Peace ushered in the Golden Age of the Cinema. A social history of the 1920’s states that the cinema was the cause of the disappearance of the street player. It gave much in return.

Prices had doubled by 1922. The cheapest seats were fivepence [2p] for the ‘pit’; stalls were ninepence [4p], and for a shilling [5p] there were chairs in the lounge. A typical programme for a week indicates the popularity of the serial film:

- Mon. – Wed.

- The Swindler

- The Phantom Foe Episode 11

- Thurs. – Sat.

- Greased Lightning

- Pirates Gold Episode 8

Episode 2 At the Palace

to Expand

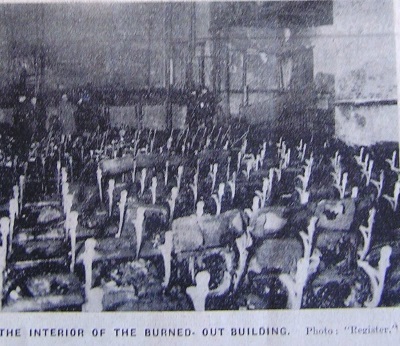

His brief occupation of the Philharmonic Hall had shown Shakespeare Shenton that a permanent cinema was a viable proposition in the town. All he lacked was a hall – but not for long. Up the back street of the Oldbury was the burnt-out shell of Walker’s Engineering Works, roofless since 1908. Within a few weeks this derelict eyesore had been transformed into ‘The Palace’.

For as little as twopence [less than 1p] – side door only – the clientele could enjoy an evening programme of films and live acts. The affluent could pay as much as sixpence [2½p]. These prices were only a half of those charged by the travelling showmen, a striking example of the benefits of a fixed site. It was far cheaper to circulate the film than cinemas.

The night of 6 December 1932 was Disaster Night. For the third time in its existence, fire ravaged the building. Shakespeare either didn’t feel up to the job or saw it as not reasonable. ‘The Palace’ was abandoned, to stay silent and shuttered for over thirty years before being demolished to make way for a new fire station. It was the end of an era. It was also the end of a nice little earner for Mabel Hewlett, the club-footed teacher at the Junior School. For a decade she had been ‘on the piano’ for the silent films.

Episode 3 Sabrina Fair

(Tewkesbury Register)Click Image

to Expand

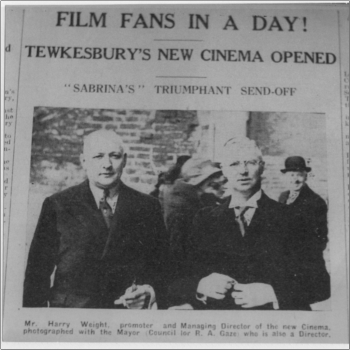

There was a touch of the old silent melodrama about the start of this period of the cinema. Enter the sinister foreigner, Oscar Deitch (in real life one of the pioneers of the large cinema). He bought 103 High Street as a site for a modern cinema. The Town Council agreed, and the magistrates granted him a licence to build. Before the work began the hero, Harry E. Weight, of Penarth, came on the scene. He would build a bigger and better cinema on the sites of 81/82 High Street. The Town Council agreed with him, but the Magistrates declined to grant a second licence. He appealed. The plot thickened. His counsel did not plead his case; rather he attacked Oscar Deitch’s proposals. His site was parallel to the railway, and would suffer from the noise of shunting engines; the same railway would make it impossible to have the emergency side exits, etc.. (Even at this date there was a strong anti-German feeling in the town.) Oscar immediately transferred his project to 89-90 High Street. No avail. His licence was revoked, and Oscar left the scene, the thwarted foreigner. Mr. Weight received his licence.

This about-face on the part of the Bench may have something to do with the following facts: Mr. Weight’s co-director was Reginald A. Gaze. The Mayor of the Borough and Chief Magistrate for 1931-34 was Reginald A. Gaze.

All this had taken some time, and it was well into 1934 before work started, yet by 6 May 1934 the ‘Sabrina Cinema’ was ready for its official opening by the Rt. Hon. W.S. Morrison, MP. For a mere £10,000 Messrs. Collins & Godfrey had built this seven-hundred theatre/cinema with restaurant and car park. By no stretch of the imagination could it be called a luxury cinema. The most imposing aspect was the front, three floors of plate glass and dazzling white concrete standing at the top of a full-width stepped approach. Behind this facade was an asbestos-roofed, steel-framed shell of light-coloured brick. One could say it was the best cinema the town ever had. At this time if you went to the cinema in nearby Upton-on-Severn and wanted a good seat, you took your own. Opening night set the style and standards for the next thirty years:

Trees and Flowers by Walt Disney, Laurel and Hardy in Busibodies with the Pathe Super Gazette and Falling For You, with Jack Hulbert and Cicely Courtneidge.

For fourpence [1½], the price of a seat in the stalls (there was no Pit now), it was a good bargain. Other prices in the stalls were ninepence [4p] and a shilling and threepence [6p]. A large balcony catered for the upper crust at two shillings and threepence [11p], where you could have your afternoon tea delivered to your seat. The Vicar of Holy Trinity, Revd. Lanham, took his dog there as well.

The last manager, Mr. Bennett, was a mine of information about the daily routine. Interviewed several years after the cinema had closed, numbers and details reeled off his tongue. From 1934 to 1944 17,000 miles of film rolled through the projectors, equal to 2,100 feature films. In 1944 the restaurant was serving 2,000 meals each month. Until 1940 the Children’s Club served many hundreds of juveniles, at fourpence a time. Restarted in 1943 it had 800 members each paying a penny for membership fees and fivepence [2p] weekly for the Saturday morning shows. There was also a free Christmas party until the hooligan element became so disruptive that both parties and club were stopped. The car park in front was usually full, with hundreds of bicycles ‘round the back’. In the years when Mr. Green was manager (1940-45), and in the first half of Mr. Bennett’s reign from 1945 to 1963, the queues frequently extended from the doors and down the High Street out of sight of the cinema. There was even a braided and bemedalled commissionaire.

The major change of these years came in 1940 with the return to the town of a large section of the BEF [British Expeditionary Force] from France. The local Commanding Officer made an early request for the cinema to be opened on Sundays. This was an appeal to Councillors and Magistrates who still insisted that the swings and roundabouts in the children’s park be locked up at midnight on Saturdays until the following Monday. A reluctant permission was given on the following conditions:

- Not to open before 6.00pm

- Servicemen only to be admitted, with one guest.

- 95% of the profits to go to a charity nominated by the bench.

- All the staff to be servicemen.

- Nobody under 16 to be admitted under any circumstances.

These rules drove a sharp wedge between the army and the population.

to Expand

After 1955 the fortunes of the ‘Sabrina’ began to ebb. Queues for admission became a thing of the past. It has been fashionable to blame television for this, but there were other factors working against the ‘Sabrina’.

The ‘Sabrina’ was an independent house. It was not included in the circuits of either the ABC or J. Arthur Rank. All films were hired at a rate based on the seating capacity of the cinema, never below 25%, usually 33% and sometimes as high as 67%. The choice of film was limited to what was not showing in the nearby towns, so the best and latest films were not shown until two or three months after they had appeared in Cheltenham and Gloucester. Nevertheless, programmes were consistently good.

Rowdyism and vandalism were steadily increasing charges upon the income of the cinema. In 1962 a seat that needed a new cover cost 30 shillings [£1.50p]; a new seat was four pounds, ten shillings [£4.50p]. Few people care to take their leisure in surroundings disturbed by a minority of louts, so they limited their visits to the cinema. The ‘Sabrina’ suffered from this disruption in moderation, in that it only became insupportable on the final night, when for the first time the police were called to eject the culprits.

Taxes were weighted against the independent operator. For Sunday shows a levy of a halfpenny per seat in the house (now reduced to 600 by the removal of some front and rear rows) was paid to the Cine Fund. When the County took over as Licensing Authority, this was doubled – regardless of whether the seat was sold. The big circuits paid only a fraction of this cost.

At a time when a good weekly wage was £15, the weekly wage bill was £90 to £100. Heating cost £20 each week on average, and the rates £900 per annum. With prices averaging three shillings [15p] a seat, inclusive of tax, the average house needed to be 200. On some evenings there were barely a dozen customers. The Borough recognised that times were hard by reducing the rates to £350, a staggering reduction measured by current (1991) standards. It wasn’t enough. The need was for customers, not charity. They didn’t come, and with the final performance of Billy Budd, the ‘Sabrina’ closed its doors for the last time.

The building lingered on for several years, isolated and derelict, proposed one day as the shell of a new cinema, on another as the basis of a swimming pool. In the end, of course, it was pulled down, some of the timber coming into the hands of a local woodcarver who produced a number of ‘Sabrina’ lamps.

Film shows did not disappear completely. The Tewkesbury Guild organised weekly shows in the Watson Hall in 1967 and 1968, and the Borough sponsored some in 1969. Then – naught until ... See next article.

![The Factory resurrected as a<br>Cinema in WWI<br>[R Wherrett,-Ebay]](/images/THS03788.jpg)

Comments