Cholera in 19th Century Tewkesbury

The arrival of cholera in England for the first time in October 1831 could hardly have come at a less propitious time. The rapid growth of the new industrial towns and cities, with their haphazard arrangements for water supply and sewage disposal, had created exactly the conditions necessary for the spread of a disease largely caused by the faecal contamination of drinking water.

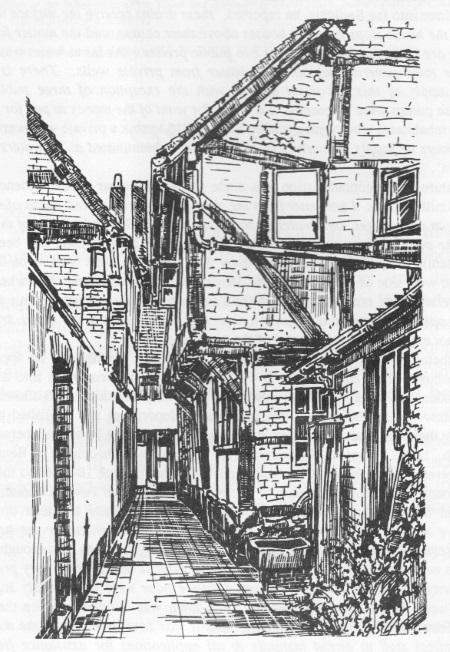

Although Tewkesbury was not an industrial town, it nevertheless suffered a cholera epidemic in 1832. The reason for Tewkesbury's susceptibility to the disease lay in the unusual way in which the town had grown. Unable to expand by developing suburbs because of the risk of flooding, the town had coped with its increasing population in the post-medieval period by creating tightly-packed housing on the burgage plots which lay behind the frontages of the High Street, Church Street and Barton Street. Access to these houses was by way of courts and alleys, of which there were over a hundred by the early 19th. century. This pattern of housing can still be seen clearly on the large-scale Ordnance Survey maps of 1895.[1]

The principal source of evidence about the cholera epidemic of 1832 is the account in the Tewkesbury Yearly Register', compiled and published annually by James Bennett.[2] In addition to giving an account of the epidemic, and of the efforts of the authorities to combat it, Bennett listed details of the 76 people who died. He included, in each case, not only the name, but also the age, occupation, residence and date of death. Statistical analysis of this data bears out Bennet's assertion that the disease 'was principally confined to the humbler classes of society' with stocking-makers and labourers (together with their families) accounting for over half of those who died. One case in five occurred in St. Mary's Lane. A quarter of all victims were children under ten years of age.

It was to be another twenty years before Dr. John Snow proved the connection between cholera and drinking water, and half a century until Ludwig Koch identified the bacillus microscopically. In 1832, Bennett could only speculate as to the cause of the disease. He noted that 'The destitute, the filthy and the dissolute, were usually the first to be attacked; and to such of these as were debilitated from previous sickness or intemperance, the disease generally proved fatal'. However, he was wide of the mark when he suggested that 'several deaths might be traced to the eagerness with which the parties had obtained possession of the wearing apparel and bed clothes of such of their relatives as had previously died of cholera', an explanation which would rather have held good for bubonic plague. Bennett deserves credit, however, for recognising the shortcomings of his own data: 'It would be impossible to state with accuracy the number of cases of malignant cholera which occurred here, in consequence of some of them not being reported to the board of health, and frequently from the difficulty of discriminating severe diarrhoea from cholera cases'.

The epidemic came to an end with the death of Margaret Jones, a 23 year-old prostitute, on September 25th. It had lasted almost exactly two months, rising to a peak in late August. The next epidemic, both in Tewkesbury and nationally, did not occur until 1849, by which time the first Public Health Act had become law. Under this Act, towns which had a death-rate in excess of 22 per 1,000, or where 10% of the ratepayers petitioned, were to be the subject of an investigation and report by a Superintending Inspector. Tewkesbury qualified for an inspection on both counts. Between March 26th. and 28th. 1849, Thomas Webster Rammell visited Tewkesbury to gather evidence for his report. He found that the average mortality between 1838 and 1844 was 27 per 1 000, 'an excess beyond the average of rates presented even by the most crowded districts of large manufacturing towns, and denoting most unequivocally the existence of local circumstances strongly unfavourable to health'.[3]

These 'circumstances' were not hard to find. Of the eight drains, five of which drained into the Avon and three into the Swilgate, he reported, 'these drains receive the surface water of the streets....as well as the house slops from the houses above their course, and the matter from the few water-closets there are in the town and from the two public privies'. As far as water was concerned he found that 'The town generally obtain their water from private wells. There is no public provision for the supply of this important article, with the exception of three public pumps'. However, since these pumps were frequently 'out of use for want of the money to pay for their being put in order' , those inhabitants who could not afford £10 to £15 to sink a private well were forced 'to beg of their neighbours or supply themselves from the Avon, contaminated as its waters are by the drainage of the town'.

The nature of the contamination was made graphically clear in the evidence given by Mary Hawkins of Smith's Lane: 'I get water from the river, and very often find lumps of nastiness in the pail. I went down once to get some water to boil some peas, and found a lump of this stuff as I was putting it in the pot'. It is no wonder that the people of St. Mary's Lane had been so badly affected in the epidemic of 1832, given that they drew their water from the Mill Avon downstream of the houses on the west side of the High Street. However, the medical men of Tewkesbury were unconvinced. Frederick Prior, medical officer to the Tewkesbury Union, concluded his evidence: 'I have expressed the opinion before, and I repeat it now, that measures insuring better drainage and water-supply will not much alter the character of the diseases of the town'.

Nevertheless, Rammell recommended that the Public Health Act be applied to the borough of Tewkesbury. This allowed the Town Council to form themselves into a permanent Board of Health under the Act, giving them powers to make improvements, and allowing them to raise rates and borrow money for the purpose. Rammell's report was not published until March 1850. Ironically, by that time, a second epidemic had taken place, killing 94 victims between August 1st. and October 8th., 1849. As before, the course of the epidemic was chronicled by Bennett.[4]

The presence of cholera in Gloucester and Worcester in June 1849 led to the formation of a temporary Board of Health composed of representatives of the Town Council, the Street Commissioners and the Guardians of the Poor. Attempts were made to clean up the town: 'piggeries, offensive mixens, and all nuisances which could possibly endanger the health of the inhabitants, were removed under their direction'. Unfortunately, this was not enough: 'The first death from cholera occurred on Aug. 1 , at which time the disease had become very prevalent and manning; and shortly afterwards the afflicted and destitute poor were gratuitously supplied with meat, twice every week, by the board of health'. The town was divided between three medical supeintendents, Messrs. Prior, Allard and Beadle, 'and it was considered to be the duty of every member of the medical staff to attend instantly to all applications for assistance from persons affected with cholera, bowel complaints, or feelings of sickness..A large proportion (at least one half) of the cases were treated according to the plan of Dr. Hawthorne of Liverpool, with highly satisfactory results. Those medical gentlemen who did not adhere to the above plan, relied on similar measures - external heat, opium and stimulants'. Once again, it was the lower classes who suffered, stocking-makers, labourers and their families making up almost two-thirds of those who died. A quarter of the deaths occurred in St., Mary's Lane, and over one-third of all victims were children under 10 years of age.

The 1849 epidemic was to be the last outbreak of cholera in the town. Fortunately for the people of Tewkesbury, the town was spared in the national epidemic of 1853-54. It is a matter of debate as to how far the Town Council can be held culpable for their painfully slow progress as a Board of Health; it took until the reappearance of cholera in London in 1853 even for them to appoint a Medical Officer of Health, for example, It was not until January 1868 that the Board of Health resolved to borrow the £2,650 needed to install a proper drainage system in the north part of the town. On January 4th.,1869, they ordered all houses within a hundred feet of the new sewer to lay down connecting drains. In the same year, construction of the Mythe Water Works by the Cheltenham Waterworks Company led to a supply of filtered and piped water from the Severn at last becoming available to Tewkesbury from the spring of 1870. In his report to the Tewkesbury Board of Health in October 1874, Mr. Allard could at last write of the alleys: 'During the last few years, much has been done to improve the sanitary condition of these localities...by increased water supply and sewerages.'

References

(GRO = Gloucester Record Office - now Gloucestershire Archives)

- OS 25"-1 mile (1885): Gloucestershire Sheet 12/9

- 'Tewkesbury Yearly Register' vol. 1 (1840)pp. 103-109

- 'Report to the General Board of Health on a Preliminary Enquiry into the Sewerage, Drainage, and Supply of Water, and the Sanitary Condition of the Inhabitants of rhe Town and Borough of Tewkesbury, in the County of Gloucester, By Thomas Webster Rammell.' (1850) [GRO: PA 329/611]

- 'Tewkesbury Yearly Register' Vol. 2 (1850) pp. 395-398

- Minutes of the Tewkesbury Board of Health (1850-74) [GRO: TBR A9/1]

Comments